Data Stories

Revealed: Majority of US Voters Support Patent Waiver on COVID-19 Vaccines

Shock poll reveals majority support for Joe Biden to suspend TRIPS and support global vaccination.

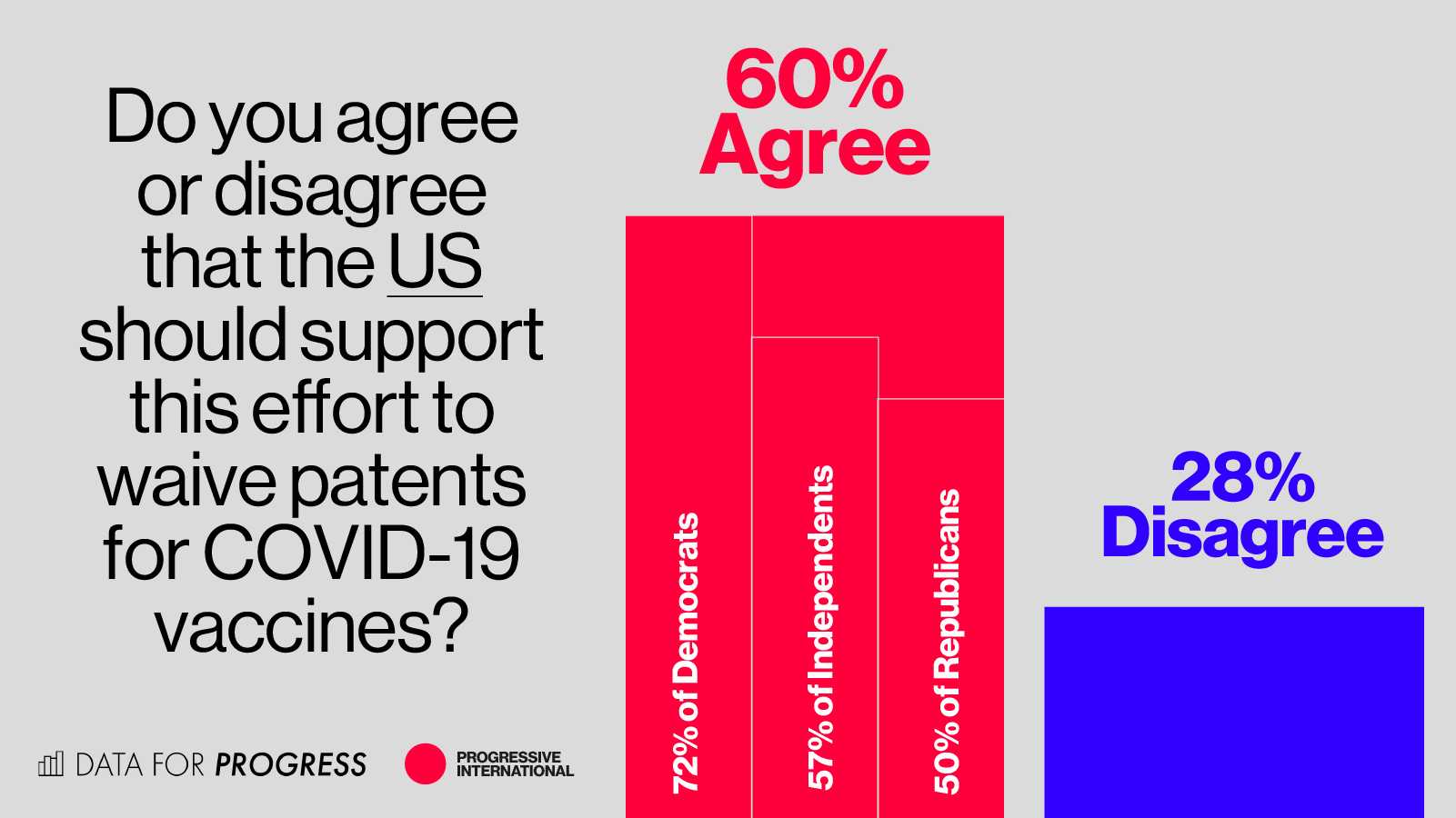

A new poll finds that 60% of US voters want President Joe Biden to endorse the motion by more than 100 lower- and middle-income countries to temporarily waive patent protections on Covid-19 vaccines at the World Trade Organization. Only 28% disagreed.

The survey, carried out by Data for Progress and the Progressive International, shows a super majority of 72% registered Democrats want Biden to temporarily waive patent barriers to speed vaccine roll out and reduce costs for developing nations. Even registered Republicans support the action by margin of 50% in favor to 36% opposed.

The new polling shows that “there is a popular mandate from the US American people to put human life and economic recovery ahead of corporate profits and a broken intellectual property system,” said David Adler, the general coordinator of the Progressive International. Burcu Kilic, research director of the access to medicines program at Public Citizen and member of Progressive International’s Council, called on Biden to “listen to Americans who put him in power” and “do the right thing.”

Due to WTO intellectual property rules, countries are barred from producing the current leading approved vaccines, including US-produced Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. In October of 2020, South Africa and India presented the WTO with a proposal to temporarily waive these rules for the duration of the pandemic so that vaccines can be manufactured across different countries, increasing their availability, reducing their cost and ensuring that they are delivered to everyone on earth as quickly as possible.

Due to WTO intellectual property rules, countries are barred from producing the current leading approved vaccines, including US-produced Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. In October of 2020, South Africa and India presented the WTO with a proposal to temporarily waive these rules for the duration of the pandemic so that vaccines can be manufactured across different countries, increasing their availability, reducing their cost and ensuring that they are delivered to everyone on earth as quickly as possible.

In the absence of the waiver, the current manufacturing and distribution rates are unlikely to stem the pandemic’s momentum, especially as new variants, which are more infectious and seem to evade the acquired immunity from prior infection or from the current vaccines, continue to emerge. The US under President Trump joined other richer nations to block them.

The shock poll reveals a level of public support for intellectual property waivers that will likely add to growing congressional pressure on Biden to join those pushing to save lives through a global vaccination drive. Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky is working on a letter to the president to which Schakowsky says more than 60 lawmakers have added their signature, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Senator Bernie Sanders, Chair of the Senate Budget Committee, responded to the poll saying the US should be “leading the global effort to end the coronavirus pandemic.” According to Sanders, “a temporary WTO waiver, which would enable the transfer of vaccine technologies to poorer countries, is a good way to do that.”

Responding to the new poll, Representative Ilhan Omar called on Biden to “support a waiver to boost the production of vaccines, treatment and tests worldwide,” arguing that it was “not just an issue of basic morality, but of public health.”

Adler argues, “US Americans know rigged rules to prop up big pharma’s profits are not in their interest. The longer the virus has to spread, the more it can mutate and become vaccine-resistant. Covid-19 anywhere is a threat to public health and economic wellbeing everywhere. If intellectual property restrictions are not lifted, the pandemic will go on for longer, killing more people and damaging more livelihoods.”

The threat to the Global South from vaccine apartheid is a “death sentence for millions around the world—and it is because giant pharmaceutical corporations would rather maximize profit than provide vaccines to people who need it,” according to Omar.

Sanders agrees, saying “the bottom line is, the faster we help vaccinate the global population, the safer we will all be. That should be our number one priority, not maximizing the profits of pharmaceutical companies and their shareholders.”

Support The Elephant.

The Elephant is helping to build a truly public platform, while producing consistent, quality investigations, opinions and analysis. The Elephant cannot survive and grow without your participation. Now, more than ever, it is vital for The Elephant to reach as many people as possible.

Your support helps protect The Elephant's independence and it means we can continue keeping the democratic space free, open and robust. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our collective future.

Data Stories

Erosion of Civil and Political Rights in Africa: Ibrahim Index (IIAG) 2020 Report

The IIAG report concludes that 2020 was a terrible year for democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa where political freedoms have deteriorated over the last decade, with citizens having less freedom to assemble in 2019 than they did in 2010.

Is there a link between democratic liberties and human rights on one hand, and good governance and economic progress on the other? Ever since the fall of the Berlin wall, a thirty-year orthodoxy has argued that the former are indispensable to the latter. However, a report by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation raises questions about this.

According to the 2020 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), political freedoms across the African continent have continued to deteriorate over the last decade, with citizens having less freedom to assemble in 2019 than they did in 2010, and the trend has accelerated since 2015. On the other hand, countries’ scores in the Human Development and Foundations for Economic Opportunity categories have improved, with the biggest strides being made in infrastructure and health.

According to the 2020 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), political freedoms across the African continent have continued to deteriorate over the last decade, with citizens having less freedom to assemble in 2019 than they did in 2010, and the trend has accelerated since 2015. On the other hand, countries’ scores in the Human Development and Foundations for Economic Opportunity categories have improved, with the biggest strides being made in infrastructure and health.

And although African countries made progress in overall governance during the last decade, the rate of improvement has slowed down over the last five years which explains the below average score in 2019.

Does this mean that the Chinese model of development—which views human and political rights as a barrier to economic progress—is supplanting the Western model, which proposes that they should go hand-in-hand on the continent?

Andrea Ngombet, a human rights activist and former presidential candidate in the Republic of Congo, says that there is more to it than that.

“To be completely honest, the combination of Chinese money, Western companies’ corruption and African autocrats’ lust for power are the causes of the retreat of democracy. All of them have no interest in a democratic Africa with tax to pay, protected workers and protected environment,” he said.

When asked why democracy is in retreat in African countries, Ngombet explained, “China [reinforces] African autocrats with cheap loans which they use for clientelism and populist projects. As the loans are without any democratic conditions, it allows the autocrats to resist the civil society pressure for democracy and accountability.”

Ngombet also explains that, “When looking at the quality of economic growth, it comes with bad loans over authoritarian regimes and those loans finance unprogressive infrastructure.”

The IIAG report shows that Gambia—the most improved of the 54 African countries—experienced the most changes after 2016 when Yahya Jammeh’s repressive 22-year-reign ended, although the current regime still faces challenges in enforcing environmental policies and in the areas of quality of education, law enforcement and compliance with international health regulations.

Source: 2020 Ibrahim’s Index

The study, whose goal was to help further the conversation on governance in the continent and assess current and emerging trends, analysed 237 variables from 40 different sources. It revealed that African countries are performing the worst in the Participation, Rights & Inclusion category (with an overall average score of 46.2 in 2019). This decline is caused by a deteriorating security situation and an increasingly “precarious environment for human rights and civic participation”.

Source: 2020 Ibrahim’s Index

Nearly half the countries on the continent had less freedom to associate and assemble and a shrinking space for political pluralism and civil society at the close of the 2010s than they had at the beginning of the decade. This was the continuation of a diminution of civil liberties in the second half of the 2000s following improvements in the first half of that decade.

In particular, compared to the country’s scores in 2010, Kenya’s scores for freedom of association and assembly as well as media freedom fell by over 20 per cent from 2015 while the indicators for transparency and accountability, as well as anti-corruption mechanisms also fell during the same period.

However, the Ibrahim report does indicate that the indicators for digital access, energy access, infrastructure and human resources in the education sector have shown a marked improvement under the current Kenyan regime. This is despite a huge debt burden and numerous unresolved corruption cases.

Increased restrictions have been placed on the establishment and operations of civil society and non-governmental organisations which have also experienced higher cases of repression and persecution in most African countries. Political parties have experienced reduced access to state-owned media and public financing for their campaigns which has curtailed their operations.

Democratic elections, the only indicator that had shown a steady improvement since 2010, took a downward spiral in 2015. Election results in countries such as Uganda, Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire, Central Africa Republic, Gabon and the Democratic Republic of Congo have been consistently disputed as the integrity of the electoral process and the independent functioning of election-monitoring bodies have been compromised.

“You can not have democratic elections in the absence of strong institutions such as Independent judiciary, a parliament that is not completely corrupted, independent press, civil societies to monitor and people to engage citizens ahead of elections and inform them by helping them understand democracy rest on their shoulders, governance rests on their shoulder, and not the person that they’ll vote in for,” Tutu Alicante, executive director at EG Justice in Equatorial Guinea explains.

“It is us that [create] democracy. It is us that [create] governance and all the security, rule of law and human development and not the person [who] as soon as elected will focus on their pockets and family.”

Countries such as Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Chad, DRC, Rwanda and Cameroon that have scored dismally in the participation, rights and inclusion category, have all been under the rule of African leaders who have clung on to power.

These findings resonate with those of the 2020 Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index which placed Chad, Central African Republic and Democratic Republic of Congo at the bottom of the rankings in democracy in Africa, measured by electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture and civil liberties.

It may be encouraging for citizens of Djibouti, Somalia and Eswatini that although their countries are among those with the least scores in terms of participation, they have registered improvements over the decade.

“Full democratic participation is essential for the development in our society. In Africa if we are thinking about Ubuntu as a basic principle of our society, then clearly democracy is needed in a way in which we all participate in order for us as a society to rise up,” Tutu adds.

Egypt has performed exceedingly well in the score for infrastructure (80/100), and health development indicators (all above 60/100) yet, surprisingly, the country is the third least performing country in Africa, after Burundi and Eritrea—with a score of 7.9/100—when it comes to participation as a principal of good governance.

Egypt has been under dictatorship since the Arab Spring overthrew Hosni Mubarak in 2011. The government has authorised the blocking of close to 500 websites belonging to news outlets, blogs and human rights organisations, and in 2017 blocked the use of internet tools such as VPNs.

Other countries that have experienced drastic internet shutdowns, legal digital restrictions and surveillance include Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Morocco, Benin, Rwanda, Morocco, DRC and Uganda. This often happens during electioneering periods or citizen protests despite “freedom of expression being a fundamental human right enshrined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the cornerstone of democracy”, according to UNESCO, an organisation to which most of these countries belong.

Countries that have managed to transition from dictatorships or civil wars, such as Sierra Leone, Gambia, Togo, Angola and Sudan manifest increasing improvement in their citizens’ access to the fundamental civil rights.

African governments are slowly becoming more inclusive and equal in the provision of public services and the creation of socioeconomic opportunities.

Kenya and Somalia have seen the most improvements under the Gender indicator. Although Kenya has faced difficulties in passing the two-thirds gender rule (leading former Chief Justice Maraga to direct that the president dissolve parliament), it has made impressive strides in providing social-economic opportunities for women and in the representation of women in the executive even though gender equality in civil rights has declined substantially.

In contrast, women in South Africa, Ghana and Equatorial Guinea are enjoying less protection against gender violence.

Is it a question of striking a delicate balance between good overall governance and maintaining the economic growth and security of a country? Or might too much freedom lead to coups and mutiny?

The EUI Democracy report ranked Mali and Burkina Faso—both of which do not have full control over their territories and experience rampant insecurity precipitated by jihadist insurgents—as the worst performing countries in West Africa in terms of democracy. They were downgraded from “hybrid regime” to “authoritarian regime”. The report concludes that overall it was a terrible year for democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 31 countries were downgraded, eight stagnated and only five improved their scores.

It is an interesting phenomenon that, despite low scores in civil and political rights, the best scores are to be found in the Foundations for Economic Opportunity and Human Development categories with 20 countries having improved their governance score in these two areas, albeit at a slowed rate in the last five years. The biggest strides have been made in the Infrastructure and Health indicators, complemented by improvements in Environmental Sustainability.

More often than not, infrastructure and health projects are marred by allegations of corruption and lack of transparency. Yet, a correlation model run by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation shows that there is a strong and positive correlation between the overall governance score and specific indicators such as rule of law and justice, inclusion and equality, anti-corruption, transparency and accountability and business environment. Even though statisticians agree that “correlation does not imply causation”, this model indicates that countries with higher scores in those indicators also have higher overall governance scores.

Yuen Ang argues that “the idea that economic growth needs good governance and good governance needs economic growth takes us to a perennial chicken-and-egg debate” whereas Meles Zenawi has claimed “There is no direct relationship between economic growth and democracy historically or theoretically. Democracy is a good thing in and of itself irrespective of its impact on economic growth and my view is that in Africa most of our countries are extremely diverse that maybe the only option of keeping relationships within nations sane. Democracy may be the only viable option of keeping these diverse nations together, we need to democratise but not in order to grow, we need to democratise in order to survive as a united same nation.”

The 2020 IIAG report paints a picture of a continent that had long embarked on the road to decline in rights, civil society space and participation before it was hit by COVID-19. Even though Africa accounts for 3.5 per cent of the global reported COVID-19 deaths, the pandemic is now threatening hard-won gains in areas such as foundations for economic opportunity and human development.

Data Stories

The Music of the Nyayo Era

Perhaps, we argue, that if we listen to the popular music of his twenty four year rule can we observe the fingerprint and maybe get a glimpse of the Man and his legacy.

This week marks the first anniversary since the death of the second president of Kenya, Daniel Torotich Arap Moi. Indeed, much has been written and said about Daniel arap Moi, and his death uncorked a litany of previously hidden details and insights into the Shakespearian drama he presided over while in office.

But how do we evaluate the legacy of Moi’s agency during his time in office?

Is it through the memoirs that will and have been written, the popular slogans that were created by his regime and sang by his supporters or is it the “official” narrative peddled by the state? Or is it, perhaps, the pain his detractors and critics faced or the scars of the victims who suffered his heavy hand?

Popular music reflects the culture of our day. Through it, we can observe the blueprint of an age in the lyrics and sound of that time.

Perhaps, we argue, that if we listen to the popular music of Moi’s twenty four year rule can we observe the fingerprint and maybe get a glimpse of the Man and his legacy.

The following is a chronological account of the sounds and hits that defined the twenty four year rule of Daniel Torotich Arap Moi.

1978: The Kenya scene is just coming off of Daudi Kabaka’s African Twist. But we must start with that style Msichana wa Elimu, a song that advises about marriage. Daudi Kabaka was born in 1939 and died in 2001, was a popular Kenyan vocalist, known by his fans as the undisputed King of twist. Jomo Kenyatta died on August 27th of 1978 and President Daniel Torotich took over as the second president of Kenya.

1979: Nico Mbarga has taken over Africa with Sweet Mother. Locally Slim Ali and The Hodi Boys Band are all the rave, playing in hotel lounges and clubs across the Middle East and North Africa and ended up in Kenya Slim Ali is from Mombasa. Here, President Moi is still loved and respected by many people. He enjoys popular support from the people. A pull-out from the Nation describes him as a humble and accessible president.

1980: Fadhili Williams re-releases Malaika. The song was first recorded by a Tanzanian musician Adam Salim in 1945. Fadhili was born in Taita Taveta in 1938 and died in 2001.

1981: Maroon Commandos and Habel Kifoto produce Charonyi Ni Wasi.

1982: The August 1st coup, a failed attempt to overthrow President Daniel Arap Moi’s government so musicians are under pressure to release unity and praise songs. The biggest hits come from Jambo Bwana by Them Mushrooms which was featured in Cheetah, a Disney film that had the phrase Hakuna Matata which became very popular when Disney released The Lion King later.

1983: Safari Sounds Band releases are recorded That’s Certified Gold. Among the biggest hits were Mama lea mtoto wangu.

1984: Moi has banned Congolese music. But he changes his mind after the release of Mbilia Bel – Nakei Naïrobi (“El Alambre”).

1985: By now the Nairobi live scene has suffered because of the effects of the 1982 coup and Moi’s informal censorship. The dark days of the Nyayo era at a crescendo. Detention without trial of many political prisoners and others flee the country at risk of facing the heavy hand of the regime. Still, a rebirth happens in the music scene led by Sal Davis and The Establishment The music isn’t politically conscious however.

1986: The many detentions of the Nyayo era has also killed the vernacular live scene. State operatives at the time saw these spaces as points of political mobilisation, but Joseph Kamaru leads a little uprising popularising Kikuyu vernacular hits.

1987: D.O Misiani and Orch come to the scene. And Shirati Band releases some seditious tracks among them Safari Ya Musoma.

1988: Mombasa Roots Band arrived on the scene with Disco Chakacha – originally released in 1986.

1989: Ten years after it was founded Muungano Choir finally created a pop smash hit Safari Ya Bamba. The following year they released Missa Luba recorded in Germany after the Berlin wall came down, ending the cold war era and the triumphant of liberal democracy.

1990: Les Wanyika released an earthshaking album. One of the biggest hits was Sina Makosa

1991: Albert Gacheru makes his way through Kikuyu Pop music. His biggest hit Mariru – Kikuyu Mugithi Songs

1992: JB Maina releases Mwanake. And Japheth Kassanga, Mary Wambui, Helen Akoth and Mary Atieno are redefining gospel music with the shows Joy Bringers and Sing and Shine.

1993: Diversification happens in Kenya’s music industry. Many acts like Sheila Tett, Musically Speaking – later Zanaziki and a boy band called 5 Alive change the music scene. Among the many tracks released by Zanaziki is a popular hit. Also, Okatch Biggy and not to forget Princess Julie who create the soundtrack to the Moi government response to HIV in Kenya Dunia Mbaya.

Mid-90s: Urban Music is now bigger than was ever expected. Another boy band Swahili Nation Mpenzi makes their way into the music scene. The opening up of Kenya’s democratic space after the repeal of section 2a in 1991, the import of American culture and growth of local media outlets drastically shifted Kenya’s music scene.

Ted Josiah brings out a guy called Hardstone – Uhiki who is loved by the growing young urban population.

Jimmi Gathu and others organise for a musician called Eric Wainaina to do the first version of a new national anthem dubbed Kenya Only

Shadez O Black are challenging Hardstone for the artiste of the year award with this smash hit: Serengeti Groove.

Still in the mid 90s there’s a cultural earthquake that changed the music scene in Kenya. Kalamashaka’s hit –Tafsiri Hii. A culmination of poor governance by the Nyayo era, the structural adjustment programs of the 80’s and 90’s and new young urban generation raised by a staple of America’s hip hop culture and Nairobi’s budding urban culture produces a socially and politically conscious movement of artists who go by the moniker Ukoo fulani.

Eric Wainaina later drops Nchi ya Kitu kidogo. The song that Moi’s government truly hated.

2000s: The music scene expands dramatically and is ungovernable A growing sign that the years of Moi were coming to an end and that he could not hold on any longer to power. Ogopa Deejays arrive in the music scene. The biggest song of those first two years, the soundtrack to the Exit if Moi. All the way from Okok Primary school Gidigidi Majimaji – Unbwogable. This song was used as a slogan by the coalition government that removed Moi from power.

–

Data Stories

Journalism and the Second Sex

Women are the untapped potential — a large, invested group of potential readers and viewers who want information that is relevant to their lives and those of their families and communities.

In March 2020, as COVID-19 spread around the world and political leaders began to realise that an immediate response to the pandemic would involve personal sacrifices and public action, politicians and their directors of public health policies took to stadiums, lecterns, and cameras to speak about the need to stay home, close schools and nurseries, and ration access to grocery stores and health services.

The men spoke of social cohesion and the need to act selflessly and responsibly. The women — who take on the greatest burden of housework, childcare and responsibility for ageing parents — sighed, took a deep breath and got to work.

In the past year, people worldwide have had to rethink the way they work, travel, educate their children, interact with their communities and maintain family ties.

And research has shown that during that weird year of stress, stillness and grief, women’s voices have largely disappeared, even though it is clear that while the long-term impacts of COVID-19 resonate through the whole of society, women have been hit the hardest financially.

How women consume news matters. Women are citizens and access to accurate, timely news is necessary for their democratic participation. It is also important as a channel to give people information about regulations, services, rights, and protections that affect them directly.

This is true at all times but particularly so during a pandemic when there are extraordinary controls on people’s behaviour and movement, and new advice on how to react to health-related issues. The pandemic has also brought with it new dangers for women: domestic violence and abuse in homes where they often feel trapped with their abuser.

A UN report on the impact of COVID-19 on men and women highlights how it has affected women disproportionately, “forcing a shift in priorities and funding across public and private sectors, with far-reaching effects on the well-being of women and girls”.

The report also warns that women worldwide have been hit harder economically by the crisis and that their lesser access to land and other capital makes it more difficult for them to weather the crisis and bounce back. In other words, there is a real danger of the pandemic leaving women weaker, poorer, and pushing them further out of the political sphere than they were before.

In such a climate it is vital that women have access to news and information that will help them survive and recover. This can be immediate, practical information about, for example, places of refuge and emergency legislation that allows them to leave their home and stay with a friend if they are in danger, even during a lockdown. And it can be broader: news about the efficacy and health impacts of vaccinations, about school closures, and the trustworthiness of politicians.

News, and in particular news organisations, can also serve another more social function: as a source of companionship, solace, identity, and entertainment. Again this is true at all times but it is particularly so with the restrictions necessitated by COVID-19 that have upended so many traditional networks and community spaces.

The first thing to understand is that men and women consume news differently, at different times of the day and in different ways. The traditional print model revolves around the idea of a man reading the paper at the breakfast table, with his wife preparing breakfast, possibly with the radio or television on in the background. Traces of these habits still remain in some countries, and many editors in Latin America, especially in Mexico and Brazil, find that print is still more popular among men, while women use TV and radio more. Overall, however, patterns of use are changing.

Patterns of news consumption are now determined by access to mobile data, broadband, and enabled devices, as well as the commute to work, types of employment, and, crucially, the time available — how women consume news has often been shaped by their domestic responsibilities. Many women also say news is a low priority for them, not something they believe they need in the course of their everyday life, and something that should not supersede other tasks.

News does not provide them with what they need; it provides neither escape nor information they feel they can utilise, and the emotions it invokes are negative. Instead, avoiding the news is often a strategic decision by busy caretakers to narrow their “circle of concern” — the things they have to think about on a daily basis.

It is clear that one of the structural inequalities COVID-19 has increased is women’s “time poverty”. Even before the pandemic, women did nearly three times as much unpaid care and domestic work as men, and in the past year, as schools and nurseries closed, women found themselves trying to juggle yet more responsibilities at home.

Women and news: an overview of audience behaviour in 11 countries, a report published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, shows that women are more likely to use TV and radio — media that can be consumed while multi-tasking — while men use print and magazines.

Men and women interact with news differently, partly through personal choices and partly in response to the way in which they are treated when they do venture into public debates.

Men often receive more comments directed at their opinions and attitudes, but women who come under attack are likely to change their behaviours and become more wary of expressing opinions publicly. And while men tend to be attacked for what they think, i.e. their arguments and political attitudes, women are attacked more for simply being women.

Data shows that in most countries women are far less likely to read news via Twitter, which can often be a prime site for trolling and harassment, than men.

Online harassment towards women uses hyperbole and sexualised language, along with more subtle suggestions that women are somehow lesser beings, undeserving of resources, and less capable than men.

This online environment may well explain the differences in how women engage with news, and how they comment and share news with their networks.

Kenyans as a rule are very interested in news. The study showed that the number of both men and women who said they are extremely or very interested in news is higher than in the other countries covered and, significantly, 73 per cent of women said they were very or extremely interested in news — a figure that is much higher than in all the other countries surveyed.

And while women in many countries rely on a trusted friend or relative, or their partner, to tell them the news, passing on the snippets they feel may be interesting or relevant to them, this is especially true in Kenya, where they rely on friends and family rather than news editors to curate their news consumption.

It is worth spending some time looking at just where women do build communities and share, and where they are likely to feel comfortable in the company of others in their network. While men are more likely to be counted as news lovers in most countries, women are still likely to spend vast amounts of time consuming news and information, albeit on different platforms, often those that are linked to their caring responsibilities.

In many countries, a portion of some women’s time is spent on other forums — often ones about parenting — that still play a significant role in how women consume news. While not all women are parents, many still join these sites to participate in a female chat forum. As a result, many women occasionally consume news through links to the original article but more frequently through summaries and the ensuing debates.

Trust in news is a multi-faceted concept and a quick glance at the data shows that, in most of the countries analysed, women and men are almost equally likely to trust or distrust news. But it is worth looking at the patterns of how people share news, and how much they trust the news they receive through social media and through private messaging apps from their close friends and family.

There is usually a positive correlation between interpersonal trust, trust in the media, and trust in other institutions.

Wealth and education matter in this area too. A person’s level of education is the strongest sociodemographic predictor of trust in the media, with men and women with lower levels of education trusting news more than those with higher levels of education.

There are some differences between how much men and women trust the news they see on social media and the news they receive through their personal networks, but overall, the trends in the trust in news move in the same direction for both genders.

But what women want from news and crucially, what they are prepared to tolerate, is also changing.

Social media has helped here. Feminists have used new platforms and new activist tools to speak out and organise against sexism and misogyny, sometimes in the news media too. We see this with the #MeToo movement, but also with important specific mobilisations around, for example, #EleNão in Brazil, #ProtestToo in Hong Kong, and many more.

In Kenya this activism comes from Kenyan women’s anger over the country’s high rates of domestic violence and femicide, and the media’s portrayal of victims as somehow complicit in their own deaths has sparked a nationwide conversation about the role of women in newsrooms.

Some recent high-profile murders have acted as lightning rods for the protests. The rape and murder of university student Sharon Otieno in 2018 is a case in point. Much of the media used her case as a hook for writing articles about sugar daddies and female students, much to the fury of women who felt the coverage took away her dignity. Protests also erupted the following year after medical student Ivy Wangechi was murdered by a man who was stalking her and the media spent a disproportionate part of the coverage on her killer’s motivations.

The anger generated a series of social media movements including the Twitter hashtag #TotalShutdownKe and the Counting the Dead project (which keeps a tally of femicide victims) which sprang up and coalesced around the Women’s Day demonstrations. Attention also turned to the dangers faced by women living with abusive partners during lockdown.

This is part of a broader trend where historically disenfranchised populations in many countries are using digital media to work around male-dominated established news media spaces they have long been excluded from. Our audience data shows that women engage with established news media in ways that are sometimes quite different from those in which men engage with news.

The growing number of women-led protest movements against femicide, sexual assault, and online harassment around the world has also created new conversations about who in the newsroom is deciding the agenda and framing the news.

Newsrooms in Kenya are still dominated by men at the higher levels, and while there have been a handful of senior newspaper editors who are women, “Kenyan female journalists have tended to cover the more traditional beats of health, science, and lifestyle”.

This has meant that the news agenda has been decided by men with women portrayed under the male gaze. There is a new generation of female investigative and political reporters who are building up impressive reputations but they frequently find themselves the target of online attacks.

Two respected female news anchors, Lulu Hassan and Kanze Dena, were subjected to an absurd level of trolling in 2017 after they interviewed Kenya’s president Uhuru Kenyatta in a wide-ranging interview that included a few soft questions about football and how he spends his free time. The comments focused on how they were asking silly questions, and were unsuited for political interviews, even though the resulting programme was a hit in terms of ratings with both men and women.

There are some initiatives to serve women audiences, but they tend to be external. The BBC has partnered with many media stations in Africa to create She Word, and The Nation, one of Kenya’s main newspapers, has a donor-funded gender desk. These initiatives have created space for news aimed at women, often by women, but they are generally seen as separate from the main news desk and their existence has little impact on the wider culture of Kenyan newsrooms.

Many media organisations are struggling to remain relevant to their readers and crucially, to persuade people to pay for journalism. Women are the great untapped potential here — a large, invested group of potential readers and viewers who want information that is relevant to their lives and those of their families and communities. In order to survive, journalism and journalists need to recognise this fact and change their message accordingly.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoBetween the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: The Choices Facing Kenya and the Kenyattas

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoIMF: Easy Scapegoat, Wrong Culprit

-

Long Reads1 week ago

Long Reads1 week agoDemocracy as Imperialism

-

Long Reads1 week ago

Long Reads1 week agoRites And Wrongs: Are we Going the Right Way About Ending FGM?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCapitalism Is Killing Us

-

Reflections1 week ago

Reflections1 week agoReflections on Tyranny and Terror in Kenya Then and Now

-

Ideas1 week ago

Ideas1 week agoKenya: Will Recognising Ethnic Identities Lead To Positive Outcomes?

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoThe African Roots of Cuban Music