Op-Eds

India’s COVID-19 Surge Is a Warning for Africa

8 min read.The surge in COVID-19 cases in India, spurred by a more transmissible variant and complacency, provides a stark warning to African populations to remain vigilant to contain the pandemic.

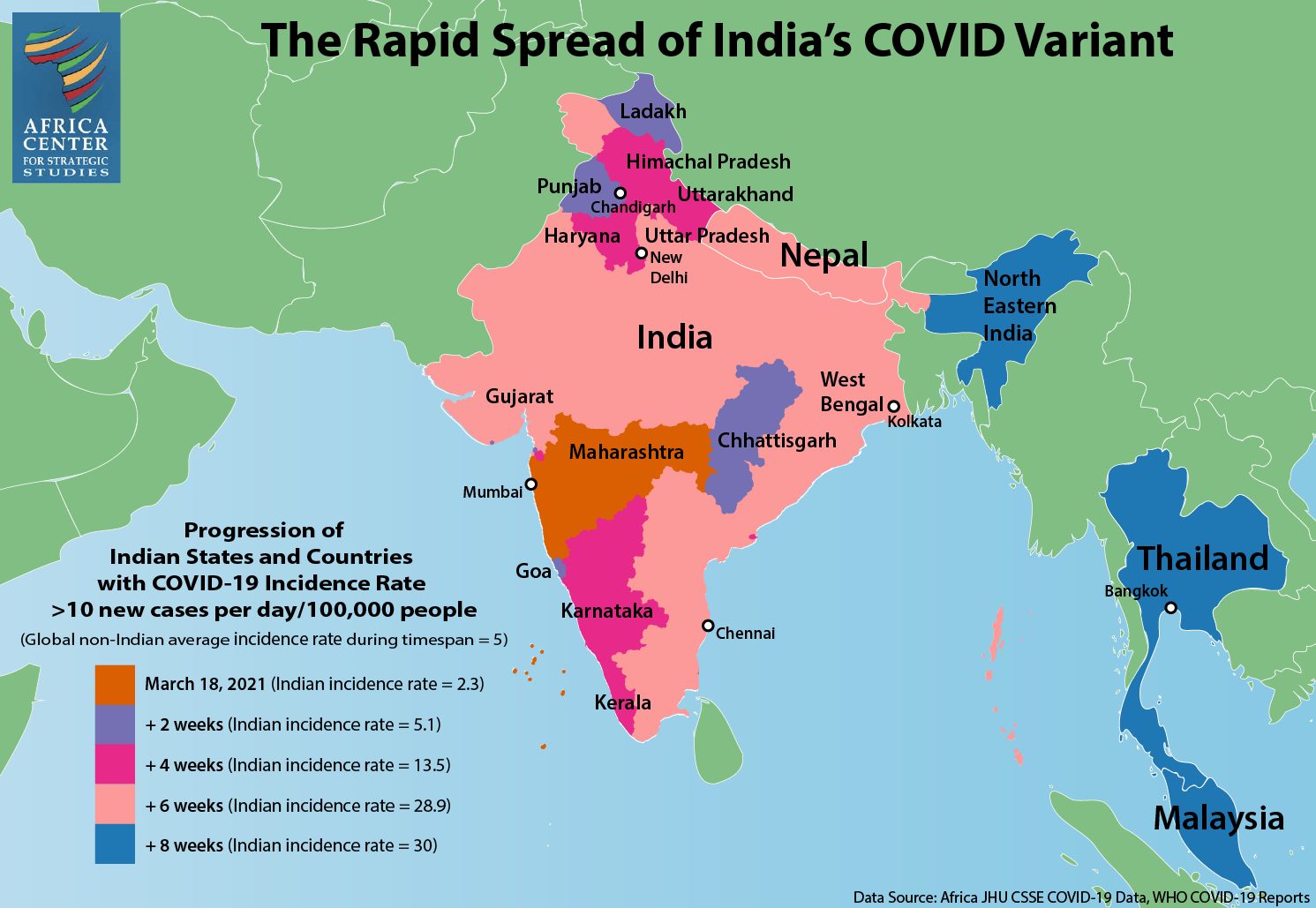

India has been grappling with a deadly COVID-19 surge that hit the country like a cyclone in early April. Within a month, new daily cases peaked at over 400,000. On May 19, India set a global record of 4,529 COVID-19 deaths in 24 hours. Over 500 Indian physicians have perished from COVID since March. The actual figures on these counts are likely to be much higher due to testing limitations. Conservative estimates indicate India has experienced over 400 million cases and 600,000 deaths overall.

India’s hospitals are overflowing with patients in the hallways and lobbies. What hospital beds are available are often shared by two patients. Thousands more are turned away. Entire families in the cities are falling ill, as are whole villages in some rural areas. Countries in the region, such as Nepal, Thailand, and Malaysia, have also experienced a sharp uptick in cases fueled by the highly transmissible Indian variant.

India’s surge is also remarkable considering the country largely avoided the worst of the earlier stages of the pandemic.

India’s COVID-19 surge is a warning for Africa. Like India, Africa mostly avoided the worst of the pandemic last year. Many Sub-Saharan African countries share similar sociodemographic features as India: a youthful population, large rural populations that spend a significant portion of the day outdoors, large extended family structures, few old age homes, densely populated urban areas, and weak tertiary care health systems. As in India, many African countries have been loosening social distancing and other preventative measures. A recent survey by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) reveals that 56 percent of African states were “actively loosening controls and removing the mandatory wearing of face-masks.” Moreover, parts of Africa have direct, longstanding ties to India, providing clear pathways for the new Indian variant to spread between the continents.

So, what has been driving India’s COVID-19 surge and what lessons might this hold for Africa?

The Indian Variant Is More Transmissible

In February, India was seeing a steady drop of infections across the country, and life was seemingly returning to normal. Unfortunately, this was just a calm before the storm. That same month, a new variant, B.1.617, was identified in the western state of Maharashtra, home to India’s largest city of Mumbai. Now widely known as the “Indian variant,” B.1.617.2 (or “Delta” variant according to WHO’s labeling) is believed to be roughly 50 percent more transmissible than the U.K. or South African variants of the virus, which, in turn, are believed to be 50 percent more transmissible than the original variant, SARS-CoV-2, detected in Wuhan.

Some experts say the emergence of B.1.617.2 represented a significant turning point. Within weeks, the new variant spread throughout southwest India and then to New Delhi and surrounding states in the north. Densely populated urban centers of New Delhi and Mumbai became hotspots. The virus then started spreading rapidly in poor, rural states across the country.

Medical professionals are saying the new variant is infecting more young people compared to the transmissions of 2020. Multiple variants are now circulating in India, including the Brazil (P.1) and U.K. (B.1.1.7) variants. Moreover, a triple mutant variant, B.1.618, has been identified and is predominantly circulating in West Bengal State. A triple mutant variant is formed when three mutations of a virus combine to form a new variant. Much remains unknown about B.1.618, though initial reports suggest it may be more infectious than other variants.

Complacency and the Loosening of Restrictions

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged as a global threat in 2020, Indian authorities implemented a strict and early lockdown, educational campaigns on mask wearing, and ramped up testing and contact tracing where they could. However, since the peak of infections in September 2020, a public narrative started to emerge that COVID-19 no longer posed a serious threat. It was also believed that large cities had reached a measure of herd immunity. The relative youth of India and its mostly rural population that spends much of its time outdoors, further contributed to the sense that India had escaped the public health emergencies seen in other parts of the world.

“Government messaging during the first few months of 2021 boosted the narrative that India was no longer at risk.”

Government messaging during the first few months of 2021 boosted the narrative that India was no longer at risk. Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared victory over the coronavirus in late January. In March, India’s health minister, Harsh Vardhan, proclaimed the country was “in the endgame of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Behavioral fatigue also set in. Mask wearing waned, as did social distancing, all while tourism opened up and people began traveling to other parts of the country as in pre-pandemic times. Leaders in the western state of Goa, a popular tourist destination, began ignoring pandemic protocols and allowed entry to tens of thousands of tourists in an effort to bounce back from the economic fallout of the 2020 lockdown. Instead, Goa is believed to be the epicenter of the 2021 surge and now has one of the highest rates of infection in the country.

People began socializing in large gatherings elsewhere in the country as well. Contradictory COVID-19 protocols that called for strict night curfews and weekend lockdowns while simultaneously allowing large weddings and mass religious festivals only added to the collective sense of confusion and complacency. Contact tracing and follow-up in the field largely stopped.

Super-Spreader Events

India’s COVID-19 surge was also seemingly driven by a variety of super-spreader events. Most prominently were two international cricket matches in Gujarat State in western India where 130,000 fans converged, mostly unmasked, at the Narendra Modi Stadium.

Unmasked crowds fill the streets during India’s Kumbh Mela Festival in April 2021. (Photo: balouriarajesh)

Prime Minister Modi, himself unmasked, campaigned in state elections at rallies of thousands of maskless supporters in March and April. In West Bengal, where voting is held in eight phases, infections have since spiked.

Thousands gathered in the state of Uttar Pradesh to celebrate Holi, the weeklong festival of colors that began on March 29. Meanwhile, millions pilgrimaged to the Hindu festival Kumbh Mela in Uttarakhand State in April, which possibly led to “the biggest super-spreader [event] in the history of this pandemic.” Leaders in Uttarakhand not only allowed the festival to take place but also openly encouraged attendance from all over the world saying, “Nobody will be stopped in the name of Covid-19.”

Warning for Africa

The recent surge in COVID-19 cases in India underscores why African countries cannot let their guard down or succumb to myths that cast doubt on how to bring the pandemic to a halt. Most directly, the Indian variant has already reached Africa. It was first detected in Uganda on April 29, 2021, and is now circulating in at least 16 African countries. Moreover, hospitals and ICUs in Uganda are now reporting an overflow of cases linked to the Indian variant. Many of the incoming patients are young people. India also shares similar social features with Africa: a young population, extended family structures that include caring for the elderly at home, and returning to less-populated rural areas of origin when crisis strikes.

Previous analysis has shown that there is not a single African COVID-19 trajectory. Rather, reflective of the continent’s great diversity, there are multiple, distinct risk profiles. Two of these risk profiles—Complex Microcosms and Gateway Countries—seem particularly relevant when assessing the Indian surge risk for Africa.

Complex Microcosms represent countries with large urban populations and widely varying social and geographic landscapes. Many inhabitants of countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Sudan, Cameroon, and Ethiopia live in densely populated informal settlements, making them particularly susceptible to the rapid transmission of the coronavirus. This group also has a higher level of risk due to their weaker health systems, which limits the capacity for testing, reporting, and responding to transmissions. Both the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria are among Complex Microcosm countries that have already detected the Indian variant.

Gateway countries, such as Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa, have among the highest levels of international trade, travel, tourism, and port traffic on the continent. This makes them more exposed to potentially more infectious and deadly variants that have emerged from other parts of the world, such as India. The interconnected nature of South Asia and the African continent is seen by the early detection of the Indian variant in Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa.

India and the African continent have strong historical, cultural, and economic bonds. Roughly 3 million people of Indian origin live on the continent, and India is Africa’s second most important trading partner after China. Southern and East Africa, in particular, have deep ties to India and large Indian populations with families on both continents. In short, there are many economic and socially driven pathways for the Indian variant to reach Africa.

Priorities for Africa

Lessons from India show that its unprecedented COVID-19 surge was driven by both a more transmissible variant as well as by letting its guard down on preventative public health measures. This exposed the vulnerability of India’s closely integrated and densely populated demographics. A number of African countries also face elevated risks to the spread of the pandemic. Learning from India’s experience highlights several priorities for Africa.

Skyline in Mombasa, Kenya. (Photo: Leo Hempstone)

Sustained Vigilance. Africa must remain vigilant since some of the same presumed protections India claimed, such as large rural populations that spend much of the day outside, may not guard against the next wave. The new Indian variants are spreading rapidly among young populations, and there is evidence that these newer variants, rather than just exploiting compromised immune systems, are causing some young healthy immune systems to overreact, resulting in severe inflammation and other serious symptoms.

This was the pattern observed in Africa during the 1918-1919 Spanish flu pandemic. The second wave of this pandemic was the result of a significantly more infectious and lethal strain that devasted the continent, infecting the young and the healthy. Countries outside Africa exposed to the mild first wave seemed to experience a reduced impact during the second wave, even though the two strains were markedly different. Having largely escaped the mild first wave, Africa was particularly vulnerable to the virulent second wave.

Continued Importance of Mask Wearing and Social Distancing. The strength of Africa’s public health system is its emphasis on prevention over curative care. African health systems do not have the infrastructure or supplies to respond to a crush of cases. Yet, many African countries have been actively loosening mask mandates and social distancing controls. On May 8, the Africa CDC hosted a Joint Meeting of African Union Ministers of Health on COVID-19 to encourage governments to overcome pandemic fatigue and invest in preparedness. With an eye toward India, prevention measures such as mask wearing, social distancing, and good hand hygiene are still as important as ever until vaccines become more readily available.

“Africa must remain vigilant since some of the same presumed protections India claimed, such as large rural populations that spend much of the day outside, may not guard against the next wave.”

Public Messaging. India suffered from confusing messaging at the early stages of the surge with prominent leaders and public health officials downplaying the severity of the risk and not modeling safe practices with their own behaviors. As they did with the initial onset of the pandemic, African leaders must convey clearly and consistently that the COVID-19 threat persists. Special outreach must be made to youth, who may feel they are immune, but who face greater risks from the Indian variant than previous variants that were transmitted on the continent. In cases where there is a low level of trust in government pronouncements, communication from trusted interlocutors such as public health practitioners, cultural and religious leaders, community leaders, and celebrities, will be especially important.

Ramping Up of Vaccine Campaigns. According to the Africa CDC, the continent has administered just 24.2 million doses to a population of 1.3 billion. Representing less than 2 percent of the population, this is the lowest vaccination rate of any region in the world. With the Indian and other variants coursing through Africa, the potential for the emergence of additional variants rises, posing shifting threats to the continent’s citizens. Containing the virus in Africa, in turn, is integral to the global campaign to end the pandemic. Recognizing the global security implications if the virus continues to spread unchecked in parts of Africa, the United Nations Security Council has expressed concern over the low number of vaccines going to Africa.

While this can largely be attributed to the limited availability of vaccines in Africa during the early part of 2021, this is changing. A number of African countries are now unable to use the doses they have available as a result of widespread vaccine hesitancy driven by myths surrounding the safety of the vaccines. Meanwhile, several African countries have not yet placed their vaccine orders with Afreximbank.

African governments and public health officials, therefore, need to ramp up all phases of their COVID-19 vaccine rollout—public awareness and education, identification of vulnerable populations for prioritization, and logistical preparations and outreach—for a mass vaccination effort to reach as large a share of their populations as possible. Africa’s well-established networks of community health workers provide a vital backbone as well as a trusted and experienced delivery mechanism to successfully achieve these objectives. With technical, financial, and logistical support from external partners, African vaccination campaigns can rise to meet the challenge.

–

This article was first published by the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies.

Support The Elephant.

The Elephant is helping to build a truly public platform, while producing consistent, quality investigations, opinions and analysis. The Elephant cannot survive and grow without your participation. Now, more than ever, it is vital for The Elephant to reach as many people as possible.

Your support helps protect The Elephant's independence and it means we can continue keeping the democratic space free, open and robust. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our collective future.

Op-Eds

Kenneth Kaunda: The Founding President of Zambia

Independence leader who fought white rule and helped shape postcolonial southern Africa

This piece was originally published in the Financial Times and is republished in the Elephant with the express permission of the author.

Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s founding president who has died aged 97, was a towering figure of African nationalism and the anti-colonial independence movement that swept the continent in the 20th century. For his 25 years in office he fought apartheid, yet was more a victim of southern Africa’s white minority regimes than an instrument of their collapse.

After taking office at independence in 1964, Kaunda banned all political parties except his United National Independence party in 1972. In 1991 he reluctantly conceded multi-party elections, in which he was soundly defeated. Nonetheless, Kaunda ruled Zambia with a rare benevolence in an era of dictatorships and systematic abuse of human rights. His Christian faith, together with socialist values, was at the heart of his doctrine of “Zambian humanism”.

At home, his policies were little short of disastrous economically. Zambia’s all-important copper mines were nationalised shortly before a fall in the commodity’s price, while industries were taken over by an administration short of managers — the country had only a dozen university graduates at independence in 1964 — and newly created state-owned farms proved a failure.

Abroad, his influence never quite matched his rhetoric. He denounced white rule but was inhibited by landlocked Zambia’s dependence on trade through neighbouring Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa. Closure of the border with Rhodesia left his country dependent on a road to the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam for its fuel imports. A Chinese-built rail link opened in 1975, but the line never met its potential.

Born at Lubwa Mission on April 28 1924 in what was then Northern Rhodesia, Kenneth David Kaunda was the eighth child of teacher parents. After secondary school he too became a teacher, but in 1949 he gave up teaching to enter politics. By 1953 he was secretary-general of the country’s African National Congress party. Impatient and ambitious, he formed his own party in 1958, which was banned a year later.

In 1960 he took over the leadership of the United National Independence party. It swept to victory in the independence election of 1964, ending Zambia’s legal status as a British protectorate. Almost immediately, Kaunda was confronted by the white Rhodesian rebels’ unilateral declaration of independence on November 11 1965.

For the next 15 years his political life was dominated by the Rhodesian bush war, which spilled over into Zambia. He provided a base not only for Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe African People’s Union but South Africa’s own African National Congress, Namibia’s South West Africa People’s Organisation, the FNLA of Angola and Frelimo from Mozambique.

His frequent tearful warnings of regional cataclysm, invariably delivered while holding a freshly ironed white handkerchief, were heartfelt but ineffectual.

Historical and geographical realities left him with a weak hand.

His decision to keep the border with Rhodesia closed hurt Zambia far more than it did his neighbour, and its eventual reopening in 1973 was a humiliating climbdown. A meeting with John Vorster, prime minister of apartheid South Africa in 1975, achieved little, while his secret talks with Ian Smith, Rhodesia’s white minority leader, served only to sour relations with Nkomo’s rival, Robert Mugabe, who was to win the elections for an independent Zimbabwe in 1980.

Pro-independence events had also left Kaunda at a serious disadvantage. The huge Kariba hydroelectric dam was built on the Zambezi river that formed the boundary with Rhodesia. Its generator was on the south bank, leaving the latter in control of power supplies to Zambia’s copper mines.

Perhaps his finest hour came when he hosted the 1979 Commonwealth conference that helped pave the way to Rhodesia’s transition to an independent Zimbabwe. The highlight was a beaming Kaunda leading Margaret Thatcher around the dance floor.

Trade union-led pressure for an end to the country’s one-party system eventually became irresistible, and in 1991 he conceded to demands for the multi-party poll that led to his ousting.

One of his last public appearances was at the funeral of Nelson Mandela, where he attempted to get the crowd of mourners to join him in a rendition of “Tiyende Pamodzi” (let us pull together), a rousing Unip anthem sung at Unip rallies.

The response was an uncomprehending silence. Kaunda had become disconnected from the Africa that he, Mandela and others had worked to shape.

–

This piece was originally published in the Financial Times and is republished in the Elephant with the express permission of the author.

Op-Eds

Cherry-Picking of Judges Is a Great Affront to Judicial Independence

Uhuru Kenyatta’s refusal to fulfil his constitutional duty to appoint and gazette JSC-nominated judges is a tyranny against the judiciary.

The 2010 constitution placed an onerous responsibility on the judiciary. That responsibility is to check that the exercise of public power is done in a manner that is compliant with the constitution. The constitution brought everyone, including the president – in both his capacities as the head of state and head of national executive – under the law. Hence, the judiciary has the final word when called upon to determine whether anything done or said to be done by anyone in the exercise of public power is constitutional.

To ensure that judges and magistrates can perform this task, the 2010 constitution created a strong architecture to secure judicial independence. In a nutshell, judicial independence simply means creating the necessary guardrails to ensure that judges and magistrates are and feel fully protected to make the right decision without fear of reprisal and that the judiciary has the facilities it needs to create an enabling environment to facilitate judges and magistrates’ abilities to undertake that core mandate. Ordinarily, the critical aspects of judicial independence include decisional, operational/administrative as well as financial independence.

Operational independence safeguards the ability of the judiciary to run its affairs without interference from other arms of government or from anyone else. Financial independence on the other hand ensures that the judiciary is well funded and fully in control of its funds so that its core duty (decision-making) is not frustrated by either lack of funds or the possibility of a carrot–and-stick approach where the executive dangles funding to extract the decisions it wants. In this regard, the constitution creates a judiciary fund and places it under the administration of the judiciary. Unfortunately, the national government and the treasury have continued to frustrate the full operationalisation of the judiciary fund.

Centrality of an individual judge’s independence

Importantly, the foundational rationale for judicial independence and its different facets is securing the decision maker’s (judge and magistrate) individual independence. This is commonly referred to as decisional independence. In the end, the judiciary exists for only one reason: to adjudicate disputes. In this regard, the person who is charged with decision making is the one who is the primary beneficiary of judicial independence. Of course, ultimately, everyone benefits from an independent judiciary.

Still, the constitution has specific and high expectation of the decision-maker, including that he or she makes decisions based only on an objective analysis of the law and the facts. The decision maker must not be mesmerised or cowed by power. He or she should never be beholden to power – in the present or the future. Simply put, under the constitution, a decision maker should never have to think about personal consequences that he or she may suffer for making a decision one way or another as long as that decision is based on an honest analysis of the law and the facts. Put a bit differently, the decision maker should never have to make (or even think of calibrating) his or her decision to please those in or with power – either within the judiciary or outside it – with the expectation that it will help him or her to obtain professional favours, promotion or to avoid reprisals.

And this is why Uhuru Kenyatta’s cherry-picking of who should or should not be appointed judge is the greatest threat to judicial independence in Kenya.

But first a quick word on what the constitution says about the process of selecting, appointing and disciplining judges.

Selection and disciplining of judges

Before 2010, the president played a controlling role in the selection of judges. This meant that the surest way to become and remain a judge was by being in the good books of the president and his handlers. The result was that the judiciary was largely an appendage of the executive – and could hardly restrain the abuse of public power by the president or other ruling elites. The 2010 constitutional provisions on the judiciary were deliberately designed to eliminate or highly diminish this vice.

The power to select judges was given to the Judicial Service Commission (JSC), a body representative of many interest groups, the president key among them. Constitutionally, the president directly appoints three of the 11 JSC members: the attorney general and two members representing the public. But with his usual ingenuity at subverting the constitution, Uhuru Kenyatta has added to this list a fourth – by telling the Public Service Commission (PSC) who should be its appointee. Regardless, while there are always endless wars to control the JSC especially by the executive, the many interests represented complicate a full takeover of the JSC by the executive or any other interests. And that is partly what the constitution intended to achieve. The law – which the court has clarified numerous times – is that once the JSC has nominated persons to be judges, the president’s role is purely ceremonial, and one that he performs in his capacity as head of state. He must formally appoint and gazette the appointment of the judges. No ifs, no buts.

This is why Uhuru Kenyatta’s cherry-picking of who should or should not be appointed judge is the greatest threat to judicial independence in Kenya.

In fact, the law further clarifies that not even the JSC can reconsider its recommendation once it has selected its nominees. There is a good reason for this unbendable procedure – it helps to insulate the process from manipulation especially once the JSC has publicly disclosed its judge-nominees. Still, the constitution preserves for the president, the JSC and citizens the option of pursuing a rogue nominee by providing the realistic possibility for the initiation of a disciplinary and removal process of a judge even after appointment if there are legitimate grounds for such action.

In this regard, the JSC also has the responsibility to discipline judges by considering every complaint made against a judge to determine whether there are grounds to start proceedings for removal. It is to be noted that the president has more substantive powers in relation to the removal of judges. This is because if the JSC determines that there are grounds for the removal of a judge, the president’s hand is mostly unrestrained with regards to whom he appoints to sit on the tribunal to consider whether a judge should be removed. Unfortunately, there is an emerging trend that indicates that Uhuru undertakes this task in a biased manner by subjectively selecting tribunal members who will “save” the judges he likes.

The injustice of cherry-picking

Now, back to the injustices of Uhuru’s cherry-picking of judges for appointment.

The injustice is horrific for both the appointed judges and those who are not appointed, especially those of the Court of Appeal. Under the 2010 constitution, you do not become a superior court judge by chance.. For High Court judges nominated to the Court of Appeal, this is earned through hard work, countless sleepless nights spent writing ground-breaking judgments and backbreaking days sitting in court (likely on poor quality furniture) graciously listening to litigants complain about their disputes all day, and then doing administrative work to help the judiciary keep going. All this while maintaining personal conduct that keeps one away from trouble – mostly of the moral kind. Magistrates or other judicial staff who move up the ranks to be nominated judges endure the same.

The injustice is horrific for both the appointed judges and those who are not appointed, especially those of the Court of Appeal

If ever there was a list of thankless jobs, those of judges and magistrate would rank high on the list. It is therefore completely unacceptable that a faceless presidential advisor – probably sitting in a poorly lit room with depressing décor and a constantly failing wifi connection, and who likely has never met a judge – can just tell the president, “Let’s add so and so to the list of judges without ’integrity’. And by the way, from the last list, let’s remove judge A and add judge Z”. Utterly unfeeling and reckless. Worse, the judge is left to explain to the world what his/her integrity issues are when he or she knows nothing about them.

Psychological tyranny

Cherry-picking also creates a fundamental perception problem. Kenya’s Supreme Court has confirmed that perception independence is a critical element of independence. For litigants appearing before the judges who were appointed in cases involving the president or the executive, it will be hard to shake-off the stubborn but obviously unfair thought that the judge earned the appointment in order to be the executive’s gatekeeper. That is what minds do; they conjure up possibilities of endless, and at times, conspiracy-inspired thoughts. Similarly, those who appear before a judge who was left out will likely believe that the judge – who decides a case impartially but against the executive – is driven by the animus of non-appointment. And you can trust the president’s people to publicly say as much and even create a hashtag for it. Yet such perceptions (of a judge who is thought to favour or be anti-executive) are relevant because justice is both about substance and perception.

And that is the psychological tyranny of Uhuru’s unconstitutional action – for both the judges that have been appointed and to those who have not. It is, indeed, a tyranny against the judiciary and, in a smaller way, against all of us. Perhaps just as Uhuru intended it to be.

Op-Eds

COVID-19 Vaccine Safety and Compensation: The Case of Sputnik V

All vaccines come with medical risks and Kenyans are taking these risks for their protection and that of the wider community. They deserve compensation should they suffer for doing so.

How effective is Kenya’s system for regulating new medicines and compensating citizens who suffer side-effects from taking them? Since March 2021, Kenya has been using the AstraZeneca vaccine supplied through COVAX to inoculate its frontline workers and the older population. This is available to the public free of charge, according to a priority list drafted by the Ministry of Health (MOH). The Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) also approved the importation of the Sputnik V vaccine from Russia, which was initially available through private health facilities only at a cost of KSh8,000 per jab, before the MOH banned it altogether. However, there were reports in the media that the vaccine continued to be administered secretary even after the ban.

Although side effects are rare, we know that all vaccines come with certain medical risks. Kenyans taking vaccines run these risks not just for their own protection, but also for that of the wider community. The state has a responsibility to protect citizens by carefully controlling the distribution of vaccines and by ensuring that adequate and accessible compensation is available where risks materialise. These duties are enshrined in the constitution which guarantees the right to health (Article 43) and the rights of consumers (Article 46).

A system of quality control before the deployment and use of medicines is set out in the Pharmacy and Poisons Act the Standards Act, the Food, Drugs and Chemical Substances Act and the Consumer Protection Act. However, the controversy over Sputnik V in Kenya has cast doubt on the coherence and effectiveness of this patchwork system. Moreover, none of these Acts provides for comprehensive compensation after deployment and use of vaccines.

Vaccine approval and quality control

Subject to medical trials and in line with its mandate to protect global health, WHO has recommended specific COVID-19 vaccines to states. Generally, WHO recommendations are used as a form of quality control by domestic regulators who view them as a guarantee of safety and effectiveness. However, some countries rely exclusively on their domestic regulators, ignoring WHO recommendations. For instance, the UK approved and administered the Pfizer vaccine before it had received WHO approval.

The COVAX allocation system fails to take into account the fact that access to vaccines within countries depends on cost and income.

By contrast, many African states have relied wholly on the WHO Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety given their weak national drug regulators and the limited capacity of the Africa Centre for Disease Control (CDC). The Africa CDC itself deems vaccines safe for use by member states on the basis of WHO recommendations. Kenya has a three-tier approval system: PPB, Kenya Bureau of Standards and WHO. The PPB relies on the guidelines for emergency and compassionate use authorisation of health products and technologies. The guidelines are modelled on the WHO guidelines on regulatory preparedness for provision of marketing authorization of human pandemic Influenza vaccines in non-vaccine producing countries. However, prior to approval by PPB, pharmaceuticals must also comply with Kenya Bureau of Standards’ Pre-Export Verification of Conformity standards .

Vaccine indemnities and compensation

To minimise liability and incentivise research and development, companies require states to indemnify them for harm caused by vaccines as a condition of supply. In other words, it is the government, and not manufacturers, who must compensate them or their families where required. Failure to put such schemes in place has undermined COVID-19 vaccine procurement negotiations in some countries such as Argentina. Indemnities can be either “no-fault” or “fault”-based’.

No-fault compensation means that victims are not required to prove negligence in the manufacture or distribution of vaccines. This saves on the often huge legal costs associated with tort litigation. Such schemes have had a contested history and are more likely to be available in the Global North. By contrast citizens of countries in the Global South must rely on the general law, covering areas such as product liability, contract liability and consumer protection. These are usually fault-based, and require claimants to show that the vaccine maker or distributor fell below widely accepted best practice. Acquiring the evidence to prove this and finding experts in the sector willing to testify against the manufacturer can be very difficult.

By default, Kenya operates a fault-based system, with some exceptions. Admittedly, citizens have sometimes been successful in their claims, as in 2017 when the Busia County Government was ordered by the High Court to compensate victims of malaria vaccines. The High Court held that county medics were guilty of professional negligence, first by not assessing the children before administering the vaccines, and second by allowing unqualified medics to carry out the vaccination.

The problem is that the manufacturer has not published sufficient trial data on the vaccine’s efficacy.

In recognition of these difficulties, and in order to ensure rapid vaccine development during a global pandemic, WHO and COVAX have committed to a one-year no-fault indemnity for AstraZeneca vaccines distributed in Kenya. This will allow victims to be compensated without litigation up to a maximum of US $40,000 (approx. KSh4 million). To secure compensation, the claimant has to fill an application form and submit it to the scheme’s administrator together with the relevant evidentiary documentation. According to COVAX, the scheme will end once the allocated resources have been exhausted. The scheme also runs toll-free telephone lines to provide assistance to applicants, although the ministries of health in the eligible countries are also mandated to help claimants file applications.

Beneficiaries of the no-fault COVAX compensation scheme are barred from pursuing compensation claims in court. However, it is anticipated that some victims of the COVAX vaccines may be unwilling to pursue the COVAX scheme. At the same time, since the KSh4 million award under COVAX is lower than some reliefs awarded by courts in Kenya, some claimants may avoid the restrictive COVAX compensation scheme and opt to go to court. Because such claimants may instead sue the manufacturer, COVAX requires countries to indemnify manufacturers against such lawsuits before receiving its vaccines.

Sputnik V

Sputnik V is different. Neither the WHO-based regulatory controls before use, nor the COVAX vaccine compensation scheme after use applies. Sputnik has not been approved by WHO or the Africa CDC. The PPB approved its importation in spite of the negative recommendation of Africa CDC, and in the face of opposition from the Kenya Medical Association. The rejection of Sputnik in countries like Kenya is partly due to the reluctance of Russia’s Gamaleya Institute to apply for WHO approval, partly because the manufacturer has not published sufficient trial data on the vaccine’s efficacy, and partly due to broader mistrust of the intentions of the Russian state. This may be changing as Africa CDC Regulatory Taskforce and European Medicines Agency are now reviewing the vaccine for approval while 50 countries across the globe have either approved its use- or are using it already. In Africa, Ghana Djibouti, Congo and Angola have approved the use of Sputnik V with Russia promising to donate 300 million doses to the African Union. Such approvals have been hailed for providing an alternative supply chain and reducing overreliance on the West.

As regards compensation, Russia has indicated that it will provide a partial indemnity for all doses supplied. However, no clear framework has been set out on how this system will work. There has therefore been no further detail on the size of awards, and whether they will be no-fault or fault-based. This lack of legal specifics has added to the reluctance of countries around the world to adopt the vaccine.

As matters stand, therefore, the Kenyan government would not be able to indemnify private clinics importing and administering Sputnik V. The absence of a statutory framework on vaccine compensation by the state makes this possibility even less likely. Nor would compensation be available from the Gamaleya Institute. The only route then would be through affected citizens taking cases based on consumer protection legislation and tort law in the Kenyan courts. As we have noted, this is complex and costly. Claims might be possible in Russia, but these problems would be exacerbated by language barriers and differences between the legal systems, as well as the ambiguity of the Russian compensation promises.

The private sector can complement state vaccination efforts, but this must be done in a way that guarantees accessibility and safety of citizens.

Although the importers obtained a KSh200 million insurance deal with AAR as a precondition for PPB authorisation, the amount per claimant was restricted to KSh1 million, which is well below the WHO rates and the average tort rates ordered by Kenyan courts. As an alternative to claiming against the manufacturers and distributors, injured patients might sue the Kenyan government. Such a claim would allege state negligence and dereliction of statutory and constitutional duties for allowing the use of a vaccine that has not been approved by global regulators such as WHO, thus exposing its citizens to foreseeable risks. This would be particularly attractive to litigants given the difficulties in recovering from the Russian authorities and the risk that Kenyan commercial importers would not be able to meet all possible compensation claims. Ironically, the use of the Sputnik V vaccine in private facilities still exposes the government to lawsuits even if it didn’t facilitate the vaccine’s importation and distribution.

What the government needs to do

The acquisition of vaccines has been undermined by the self-interested “nationalism” of states in the Global North. Only after buying up the greater part of available vaccines have they been willing to offer donations to the rest of the world. These highly publicised commitments fall far short of what is required in the Global South. Kenya’s first task must be to intensify its diplomatic efforts to increase supply through bilateral engagement with vaccine manufacturing states and in multilateral fora like the World Trade Organization, acting in alliance with other African states. Such steps are only likely to bear fruit in the medium term, however. In the short term, it is certainly sensible to involve private companies in vaccine procurement and distribution in order to supplement the supplies available through COVAX. This is recognised in Kenyan and international law as an acceptable strategy for securing the right to health. But it must be done in a way that guarantees accessibility and the safety of citizens. Accordingly, Kenya should encourage Russia (and all vaccine manufacturers) to publish full trial data showing effectiveness and risks, and to seek WHO approval on this basis. It should require them to establish and publicise detailed indemnity frameworks to allow for comprehensive and accessible compensation. It should acknowledge that citizens accepting vaccines are not only protecting themselves, but also the wider national and global community. With adequate regulation before use, the risk of doing so can be minimised and made clearer. But some risk remains, and those who run it deserve to be compensated for doing so. It is therefore imperative for Kenya to establish its own no-fault indemnity scheme for all state-approved vaccines, including those imported by the private sector.

–

This article draws from COVID-19 in Kenya: Global Health, Human Rights and the State in a time of Pandemic, a collaborative project involving Cardiff Law and Global Justice, the African Population and Health Research Centre, and the Katiba Institute, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK).

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoFrom Shifta to Terrorist: A Shifting Narrative Of Northern Kenya

-

Long Reads1 week ago

Long Reads1 week agoThe West and Its African Monsters Syndrome

-

Reflections1 week ago

Reflections1 week agoHamba Kahle Kenneth David Kaunda, Pillar of African Liberation Struggles

-

Op-Eds1 week ago

Op-Eds1 week agoGone Is the Last Of the Mohicans: Tribute to Kenneth Kaunda

-

Videos1 week ago

Videos1 week agoSomaliland: Eastern Africa’s Strongest Democracy!

-

Op-Eds1 week ago

Op-Eds1 week agoCOVID-19 Vaccine Safety and Compensation: The Case of Sputnik V

-

Op-Eds1 week ago

Op-Eds1 week agoVaccine Internationalism Is How We End the Pandemic

-

Op-Eds5 days ago

Op-Eds5 days agoCherry-Picking of Judges Is a Great Affront to Judicial Independence