Long Reads

Fake Fight: The Quiet Jihadist Takeover of Somalia

26 min read.The Federal Government of Somalia has spent the past four years waging a war on federalism, on political pluralism and on democratic norms, but not on Al-Shabaab.

On 26 October 2021, I was convicted of espionage by a Somali court and sentenced to five years in prison. The court also ruled that Sahan Research, a thinktank I co-founded and now advise, will be banned in perpetuity from Somalia. Fortunately, I wasn’t present at the time or I would have been manacled, taken away to a cell and probably prevented from writing this article on my well-worn MacBook. But then, I wasn’t meant to be present in court, let alone arrested and incarcerated: I’d been declared persona non grata and banned from entering Somalia three years earlier.

Relatively speaking, I was let off fairly easy. Somalis who cross the ruling cabal in the presidential palace, Villa Somalia, generally fare much worse. Since Mohamed Abdillahi Farmaajo took office as president in 2017, 12 journalists have been killed in Somalia, and in 2021 alone, dozens have been arrested, making the country one of the most dangerous places for media professionals across the globe. Prominent opposition politicians, including two former presidents, have been the targets of assassination attempts staged by government forces. Another has been detained since 2018 without charge or appearance before a court. The disappearance and alleged murder of a young female intelligence officer at the hands of her superiors ignited a national scandal that the government has aggressively quashed.

The shoddy episode of judicial theatre that resulted in my conviction was never about espionage, national security or any of the other charges put forward by the prosecution. It certainly wasn’t about justice. And it wasn’t even about me. Like so many other things about the Somali Federal Government (FGS) headed by President Farmaajo, it was an exercise in smoke and mirrors: a way of distracting, deflecting, and deterring anyone who might dare to question, or even contradict, Villa Somalia’s grotesque version of the “truth”.

For a start, there was virtually no attempt to create even the illusion of due process. The Attorney General filed charges with the Banaadir regional court, which has no jurisdiction to try cases involving federal crimes – crimes against the state – but which proved conveniently amenable to guidance from the presidency. Indictments were announced by press release and no summons were issued. When Sahan’s lawyer presented himself at the first hearing, he was asked to leave on the grounds that the court had already appointed defence counsel and his presence would only complicate things. The charges proffered by the prosecution alleged espionage and the revelation of state secrets, but in public the government insisted that Sahan published only lies – an assertion entirely at odds with the charge of revealing national secrets. Were we guilty of telling the truth (and too much of it) or lying? The government didn’t seem able to make up its mind. Either way, no evidence was presented in support of the charges, no witnesses were put forward, and no one ever bothered to record statements from the defendants. It was, in the truest sense of the term, a “show trial”.

State Capture, Farmaajo Style

The first lines in the script of this courtroom drama had been inked three years earlier during the lead up to elections in Somalia’s South West State (SWS), where a charismatic former Al-Shabaab leader, Mukhtar Roobow, had decided to run for president. Villa Somalia had thrown its weight behind a rival politician, Abdiaziz Laftagareen, and was incensed by Roobow’s candidacy: not because of his former jihadist affiliation, but because he commanded significant local support and would likely prove to be a strong and independent state leader. Farmaajo’s administration was in the early stages of a plan to dismantle Somalia’s nascent federal architecture and centralise all power in Mogadishu. To pursue that aim, he needed weak, pliable proxies in charge of each of Somalia’s Federal Member States (FMS). Villa Somalia made no secret of its opinion that Roobow didn’t fit the profile.

Farmaajo’s inner circle, led by his intelligence chief, Fahad Yasin, decided to nip Roobow’s ambitions in the bud through a simple, brutish ruse: they convinced the commander of the Ethiopian AMISOM contingent in SWS to invite all presidential candidates to a security briefing on 13 December 2018 where Roobow was forcibly abducted and transferred to the custody of Fahad’s bureau: the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) in Mogadishu. He has since remained in NISA custody without charge or appearance before a court.

Roobow’s arrest triggered street protests for three days, which the police quelled with deadly force, killing 15 demonstrators, including a member of the state parliament. Some 300 more were arrested and detained without charge beyond the constitutional 48-hour limit. Baidoa’s police force was largely trained and paid for by international donors through a UN-supervised programme, for which Sahan served as third-party monitor. The police crackdown was widely reported in the media and by various monitoring groups, including Sahan, contributing to a decision by three of the programme’s donors to suspend their support. The Special Representative of the UN Secretary General (SRSG), a highly respected South African lawyer and diplomat named Nicholas Haysom, also expressed his concerns in the context of the UN Human Rights Due Diligence Programme, which governs support to security forces. Three days later the FGS declared him persona non grata (which, legally speaking, it cannot do to UN officials), and he was recalled from his post by UN headquarters.

Were we guilty of telling the truth (and too much of it) or lying? The government didn’t seem able to make up its mind. Either way, no evidence was presented in support of the charges, no witnesses were put forward, and no one ever bothered to record statements from the defendants. It was, in the truest sense of the term, a “show trial”.

Haysom’s expulsion achieved precisely what the FGS leadership had hoped it would: a chilling effect on much of the remaining diplomatic community in Mogadishu. If the SRSG could be sacked simply for doing his job, who else could possibly stand up to Villa Somalia and prevail? FGS officials, especially those involved in the security sector, from the president’s doltish National Security Advisor (NSA) all the way on down to dubiously qualified ‘technocrats’ in the Ministries of Internal Security and Defence (even those whose salaries were paid for by their donor counterparts) took the lesson to heart: browbeating and tantrums became their default behaviour in encounters with foreign colleagues.

Having fulfilled its obligation as a third-party monitor to report on police brutality, Sahan also felt compelled to flag a much broader strategic concern: Villa Somalia’s intensifying efforts to weaken Somalia’s FMS and to dismantle the federal structures mandated by the Provisional Constitution – especially FMS police forces. Few observers realised that the police crackdown in Baidoa had not been led by the SWS state police, but by a few dozen federal police officers operating under direct orders from Mogadishu. On 17 December 2018, following an interview I gave to the Washington Post about how Roobow’s arrest was symptomatic of Villa Somalia’s centralist, authoritarian tendencies, Sahan was banned from Somalia and I was declared persona non grata.

Villa Somalia was not to be deterred by a little bad publicity: in August 2019, the FGS attempted to hijack elections in Jubaland, unsuccessfully financing rival candidates and ultimately declaring the re-election of state president Ahmed Madoobe null-and-void. Later the same month, in collusion with Villa Somalia, the Ethiopian army secretly attempted to airlift several hundred commandos from Baidoa to Kismayo, with a view to ousting Madoobe from office. This ended in a tense standoff between Ethiopian and Kenyan troops at Kismayo airport that could have easily ended in armed clashes between the two erstwhile allies. While Madoobe, with the support of AMISOM’s Kenyan contingent, continued to dig in and defend his seat, Villa Somalia deployed troops to Jubaland’s northern Gedo region, wresting most of it from Madoobe’s control (with Ethiopian help) and arresting Jubaland’s Minister of Internal Security.

Galmudug’s election was stolen in February 2020 and Hirshabelle’s followed suit in November the same year. In both cases, federal financing backed by the deployment of loyalist, Turkish-trained special forces and paramilitary police helped to ensure that Villa Somalia’s candidates emerged victorious. But, as in SWS, these were hollow victories: weak, proxy leaders proved unable to consolidate their wins and largely incapable of exercising state authority, ceding territory to Al-Shabaab. Through its electoral machinations, Villa Somalia had succeeded in exerting greater and greater control over less and less of the country.

Somalia’s Security Sector: Reinforcing Failure

While Villa Somalia’s brazen theft of elections and suppression of dissent served to weaken the autonomy of the FMS and enfeeble the federal checks and balances built into the Provisional Constitution, the deployment of security forces for the same purposes illustrated another, equally troubling development: the FGS had abandoned the fight against Somalia’s single greatest security threat – Al-Shabaab.

On paper, Somalia’s 2017 National Security Architecture and New Policing Model assign primary responsibility for domestic security, including counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, to the FMS. But in May 2018, the FGS issued a new Somalia Transition Plan (STP), effectively tearing up those previous agreements and clawing back all security functions to the federal level. Under the STP, Villa Somalia systematically obstructed security assistance to the FMS and funnelled resources almost exclusively to the alarmingly dysfunctional federal forces.

The STP also made promises upon which it utterly failed to deliver – with just two exceptions: Mogadishu stadium and the Jaalle Siyaad military training academy were both ceremonially transferred from AMISOM’s control to the Somali authorities. These accomplishments were, to be generous, ‘low-hanging fruit’.

More importantly, the STP promised to secure the main supply routes (MSRs) between Mogadishu and three strategic towns in neighbouring FMS: Baidoa, Baraawe and Beledweyne. At the time of writing, this pledge had spectacularly failed. For example, Leego, in Lower Shabelle region, lies just a little more than 100 kilometres from the capital and was specifically cited in the STP as a key objective in opening the road to Baidoa. Leego is also a vital Al-Shabaab financial hub, collecting hundreds of thousands of dollars each month in road taxes. More than two years since the STP was first announced, no operation has ever been staged to seize it and the road to Baidoa remains, for government purposes, closed.

In 2019, a much-vaunted offensive to clear Al-Shabaab from Lower Shabelle region and open the MSR to Baraawe, nicknamed Operation Badbaado, ultimately fizzled out and was quietly abandoned. The offensive’s greatest achievement was the recapture, in early 2020, of Janaale, which had been abandoned after Al-Shabaab overran a Ugandan Forward Operating Base there in 2015. But between Mogadishu and Janaale, Operation Badbaado succeeded only in establishing a string of disconnected outposts, isolated from one another by large rural spaces controlled by the jihadists. The MSR to Baraawe remained closed.

The STP’s pledge to open the MSR from Mogadishu to Beledweyne was especially poignant. Until 2017, the section of road between the capital and Jowhar had been safe to travel, but less than a year after Farmaajo took office, it had become too hazardous for non-military traffic, forcing government officials, aid workers and civilians to make the 90-kilometre journey by air. In May-June 2021, Somalia’s boyish Chief of Defence Forces, General Odowaa Yusuf Rageh, personally led a flurry of aimless and uncoordinated raids into Middle Shabelle. The gesture amounted to little more than a series of chaotic skirmishes, producing nothing but unnecessary casualties and bad blood between the Somali National Army (SNA) and AMISOM, which claimed that Odowaa had failed to coordinate his amateurish expedition with the AU Force Headquarters. The road to Jowhar remained effectively impassable, as did the stretch between Jowhar and Beledweyne.

Shielding Al-Shabaab

Whereas the shambolic state of the federal security forces might be explained by a combination of incompetence, inexperience, and a mediocre monocracy, the unchallenged expansion of Al-Shabaab’s influence on Farmaajo’s watch suggests a far more sinister explanation: tacit collusion between Villa Somalia and its putative adversaries. Indeed, the jihadists are possibly the only authority in Somalia that the FGS hasn’t chosen to pick a fight with.

Al-Shabaab is steadily extending its influence, not only in the interior, but even in territories nominally under some form of government control – including Mogadishu. As Farmaajo entered the latter half of his four-year term, a consensus was emerging that the terror group taxed more efficiently, raised more money, provided greater security, and dispensed higher quality justice than the FGS did. Major businesses in the capital readily acknowledged that they paid taxes to Al-Shabaab because the government could not shield them from the consequences of disobedience. Some of the country’s largest telecoms and financial institutions were found non-compliant with due diligence standards and even minimal anti-money laundering/countering terrorist financing best practices, enabling Al-Shabaab to make routine use of their services – including highly irregular transactions that should have raised red flags. The FGS, for its part, makes little or no effort to enforce its own regulations in this regard. The more Farmaajo’s social media legions huff and puff about his government’s successes, the more obvious it becomes that the war against Al-Shabaab is being lost.

These were hollow victories: weak, proxy leaders proved unable to consolidate their wins and largely incapable of exercising state authority, ceding territory to Al-Shabaab. Through its electoral machinations, Villa Somalia had succeeded in exerting greater and greater control over less and less of the country.

While the STP produced one military debacle after another, other FGS security initiatives demonstrated comparatively high levels of capability, competence, and determination in quashing Villa Somalia’s enemies: not Al-Shabaab, but rather the political opposition and recalcitrant leaders of insubordinate FMS. For this purpose, Villa Somalia relied not on forces trained, supported, and monitored by Western security partners, but rather upon those established and equipped by its more steadfast political allies: Qatar, Turkey, and Eritrea. In other words, the FGS is fighting two different wars using two very different armies.

The cornerstone of Villa Somalia’s parallel security policy was NISA under the direction Fahad Yasin. Having initially served as Farmaajo’s Chief of Staff, Fahad was appointed Deputy Director General of NISA in August 2018 and effectively ran the organisation until his official promotion to NISA chief the following year. With financial and technical support from Qatar, Fahad has transformed NISA from a decrepit, thuggish secret police force into a modern, capable intelligence service and the secretive core of Villa Somalia’s power. From behind the walls of NISA’s sleek, opulent new headquarters, he has overseen the formation of an entirely parallel security establishment.

Some elements of these forces were highly visible. In early 2018, Turkey began training the first batch of army special forces known as Gorgor (Eagle); later the same year Ankara expanded its training programme to include a new paramilitary special police unit named Haram’ad (Cheetah). Both units have since been equipped with modern weapons, equipment, and armoured vehicles of Turkish manufacture. As their numbers have expanded, Fahad has deftly manoeuvred to bring them discreetly under Villa Somalia’s direct control – and NISA’s in particular.

In 2019, plans were set in motion for another paramilitary force to be stood up, this time as an integral part of NISA. As many as 7,000 Somali youth were recruited on the promise of training and employment in Qatar, but secretly transferred instead to Eritrea. Those that subsequently returned to Somalia became known as Duufaan (Hurricane), while an indeterminate number remained trapped in Eritrea, largely incommunicado, sparking a blistering scandal back in Somalia, where their parents demanded information about their whereabouts and well-being. By some accounts, hundreds, possibly thousands, of these Somali trainees may have been dispatched to fight in Ethiopia in November 2000 against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, but a communications blackout on the conflict zone has made such reports difficult to verify.

Thousands more trainees were enlisted into the Xoogga Wadaniyiinta (Popular Forces), a largely unarmed youth militia apparently inspired by the Guulwadayaal (Victory Pioneers) of Siyaad Barre’s ruling party. And perhaps the smallest NISA unit, known as Ruuxaan (Ghosts), operates in hit squads, conducting political assassinations mainly in Mogadishu. NISA also possesses two armed units trained and mentored (and quaintly misnamed) by the US government: Waran (Spear), which protects NISA facilities and Gaashaan (Shield), which serves as a counterterrorism commando unit. But since the Americans keep an eye on them, they don’t suit Fahad’s purposes.

Fahad’s strategy for the use of these politicised units progressively took shape in 2019 during the course of interventions in Jubaland and Galmudug. Following Ahmed Madoobe’s re-election in August 2019, and Villa Somalia’s humiliating failure to have him ousted by Ethiopian commandos, Fahad formulated a new course of action to destabilise Jubaland and undermine Madoobe’s authority. The FGS surged federal forces into Gedo region, whose Marehan clan elites were divided in their loyalties between Madoobe (and his Marehan political appointees) and their kinsman, Farmaajo. Villa Somalia counted on the combination of force and finance to wrest Gedo from Jubaland’s tenuous control.

To reinforce the SNA units stationed in Gedo, which were mainly drawn from local Marehan militias, the FGS airlifted a combination of NISA’s Duufaan and paramilitary Haram’ad police from Mogadishu to change the balance of forces on the ground. More importantly, Fahad took direct control of the joint operation, dispatching his trusted NISA deputy, Abdullahi Adan Kulane ‘Jiis’, himself a member of the Marehan clan, to supervise their operations. Official military and police chains of command were short-circuited.

Violence in Gedo escalated, and casualties mounted through early 2020, threatening to draw Ethiopian and Kenyan troops into a confrontation on behalf of their local allies. In February 2020, as the situation threatened to deteriorate even further, the US government expressed its concern in a statement to the UN Security Council, describing the deployment of federal forces to Gedo region as an unacceptable “politically motivated offensive” that diverted resources away from the common fight against Al-Shabaab. But of course, that had always been the point.

Indeed, Al-Shabaab was the principal beneficiary of Villa Somalia’s hijinks. While federal forces focused on wresting control of Doolow and Buulo Hawa away from Jubaland, they made no move towards Al-Shabaab’s nearby base at El Adde, which at least 150 Kenyan soldiers had died defending in 2016, and which has since served as a critical operational and bomb-making hub for the jihadists. Other parts of Gedo region previously under Jubaland control also fell steadily under the influence of the jihadists. Today, Al-Shabaab controls more of Gedo than it had before Farmaajo took office.

Meanwhile, since late 2019, Villa Somalia had been plotting to take full control of Galmudug, dismantling its incumbent administration and engineering a rigged election to install a political proxy as state president the next year. The dynamics in Galmudug were very different from those in Gedo, but the FGS playbook was much the same. Loyalist federal forces were surged into Galmudug to achieve local security dominance and the cash followed in suitcases.

The unchallenged expansion of Al-Shabaab’s influence on Farmaajo’s watch suggests a far more sinister explanation: tacit collusion between Villa Somalia and its putative adversaries. Indeed, the jihadists are possibly the only authority in Somalia that the FGS hasn’t chosen to pick a fight with.

Roughly 120 troops from the 2nd Battalion, Gorgor Commando Brigade were airlifted to the regional capital, Dhuusamareeb, together with about 100 Haram’ad paramilitary police and 120 officers from the Banaadir Police Force, who had originally been part of NISA. Their commander, Sadiq Joon, had previously served as NISA commander in Banaadir. Villa Somalia also tried to involve US-trained and -mentored Danab (Lightning) special forces in its conspiracy, but this was quickly detected and shut down.

Like in Gedo, Villa Somalia established a discreet, informal chain of command that reported directly to NISA, with Sadiq Joon directly supervising the SNA and Haram’ad operations, in addition to his own Banaadir Police contingent. In parallel, Fahad entrusted a close aide named Ali Wardheere (or Ali ‘Yare’) with the financial arrangements, which involved bribing local politicians, clan elders, and leaders of the powerful Sufi militia, Ahlu Sunna wal Jama’a (ASWJ) to acquiesce in the FGS’ scheme.

Ironically, the principal threat to Villa Somalia’s plans came from then Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire, who tried to outmanoeuvre Fahad using his own ‘fixers’ to influence the Galmudug electoral process – a reckless overreach that ultimately cost him his job. But Fahad prevailed and his chosen flunky, Ahmed Abdi Kariye ‘Qoorqoor’, was duly installed as Galmudug’s president in February 2020

As in Gedo, Farmaajo and Fahad had employed loyalist federal forces to subvert the autonomy of an FMS – not to fight Al-Shabaab, which controlled the entire southern part of Galmudug. On the contrary, by installing a feckless political proxy and dismantling the vehemently anti-Shabaab ASWJ, Fahad prepared the ground for aggressive Al-Shabaab expansion the following year, followed by the most significant offensive by federal forces for over a decade – in support of the jihadists.

The Return of Al-Itihaad Al-Islaam

Al-Shabaab was not the only Islamist group to benefit during Farmaajo’s term of office. A little-known, like-minded affiliate known as Al-I’tisaam b’il Kitaab wa Sunna had also been growing from strength to strength – mainly thanks to the influence of its powerful representative in Villa Somalia: Fahad Yasin. Widely credited with having engineered Farmaajo’s 2017 electoral victory, Fahad had initially been rewarded with the post of Chief of Staff at the Presidency, followed by the leadership of NISA. With generous support from Qatar, he was able to refurbish NISA, not only as the most powerful instrument of FGS political authority, but also as a de facto secretariat for Al-I’tisaam.

Al-I’tisaam and Al-Shabaab share a common ancestor: the jihadist movement Al-Itihaad Al-Islaam, which first revealed itself following the collapse of the Siyaad Barre regime in 1991. Like Al-Qa’ida, Al-Itihaad was an offshoot of the militant Al-Sahwa (Awakening) movement that had been forged in the crucible of the Afghan jihad and which espoused an extreme, intolerant, and explicitly violent version of Islam. Al-Sahwa’s hostility to the Saudi establishment saw its proponents, including Osama bin Ladin, imprisoned or exiled. But Bin Ladin was welcomed by the ascendant Islamist government in Sudan in 1991, and he soon found an eager ally in Somalia’s Al-Itihaad.

Together, between 1992 and 1994, they strove to confront US military intervention in Somalia. But AIAI’s ambitions exceeded the narrow military goals of Al-Qa’ida and, against Bin Ladin’s advice, the movement sought to establish an Islamic ‘emirate’ on Somali territory. Their harsh attempts to pursue this objective found little purchase amongst the Somali population and backfired. Their ideology particularly alienated Somalia’s majority Sufi population by blaming Sufism for all the nation’s ills, including the collapse of the state. In 1996, following Bin Ladin’s expulsion from Sudan and relocation to Afghanistan, a much-deflated AIAI suffered successive defeats at the hands of the Ethiopian military and, in early 1997, made its calamitous last stand in Somalia’s southwestern Gedo region.

Among the young militants who survived Al-Itihaad’s final battle and escaped to neighbouring Kenya was Fahad Yasin. Born in 1977 or 1978 (his Somali and Kenyan passports contain different dates of birth and different names), his parents separated when he was young and he was raised by his mother and his stepfather, receiving a religious education in Mogadishu. When the Barre regime collapsed in 1991, Fahad and his family fled to Kenya as refugees, but he soon returned to Somalia under the wing of his stepfather, who had joined Al-Itihaad. Al-Itihaad’s military leader at the time was Hassan Dahir Aweys: an unrepentant extremist with whom Fahad would develop an almost filial relationship over the coming decades. Fahad’s stepfather was killed in battle against the Ethiopians in 1997, and when Al-Itihaad’s surviving leaders dispersed, the young Fahad found himself adrift.

After a couple of years searching for a new cause, Fahad eventually tried his hand at journalism, blogging for a provocative website called Somalitalk, where he mainly posted political commentary. A supporter of interim president Abdiqasim Salaad Hassam, who notionally held office as head of the then Transitional National Government between 2000 and 2004, Fahad was reportedly discouraged when Abdiqasim was ousted by Ethiopian-backed warlords through a skewed regional ‘peace process.’ Telling friends that he wanted to study Arabic, he travelled to Yemen, where regional intelligence sources say he enrolled at El Iman University: a sort of international finishing school for jihadists founded by Sheikh Abd al-Majid al-Zindani, a close spiritual adviser to Osama bin Ladin and a specially designated global terrorist (by both the US and UN) in his own right.

By some accounts, hundreds, possibly thousands, of these Somali trainees may have been dispatched to fight in Ethiopia in November 2000 against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, but a communications blackout on the conflict zone has made such reports difficult to verify.

While Fahad was carving out a career for himself in the aftermath of Al-Itihaad’s 1997 defeat, the movement’s other alumni had divided into two wings: one, asserting that Somalia was not yet ripe for jihad, pursued political and economic interests, while advancing the core tenets of Al-Sahwa’s radical ideology by establishing an underground organisation (tanzim) and by preaching (da’wa). They called themselves Al-I’tisaam. The other faction, unwilling to abandon the path of jihad, sought out foreign fields of battle on which to hone their beliefs and skills: notably Afghanistan, where they renewed their allegiance to Bin Ladin and Al-Qa’ida. Following America’s invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, veterans of these foreign battles would return to Somalia – their allegiance to Al-Qa’ida firmly intact – to establish the terror group that eventually became known as Al-Shabaab.

In the late 2000s, as Al-Shabaab emerged from the shadows to become a household name, Fahad Yasin found a job as a correspondent in Somalia for Qatar’s Al-Jazeera news network. Not surprisingly, given his jihadist credentials, he enjoyed unique access to Al-Shabaab’s senior leaders, apparently having no difficulty in obtaining exclusive interviews with reclusive ‘high value individuals’ or ‘HVIs’ whom Western intelligence agencies were desperately seeking to locate and, one way or another, remove from the battlefield.

During the course of his relationship with Al-Jazeera, Fahad apparently forged close ties with Qatar’s intelligence services, becoming a valued asset and, ultimately, an agent of influence. By 2011, he was back in the Somali political arena, working in the entourage of President Hassan Sheikh, who was elected to office in 2012. There was not much room in Hassan’s administration for Fahad to shine: although no Islamist himself, Hassan’s kitchen cabinet was dominated by members of Dam ul-Jadiid, an activist offshoot of Harakaat Al-Islaax (Somalia’s chapter of the Muslim Brotherhood), whose progressive ideals had little in common philosophically with Fahad’s conservative, militant upbringing. Moreover, Fahad was politically overshadowed by a close relative, Farah Abdulqadir, who outranked him within the clan hierarchy and served as Hassan Sheikh’s closest advisor.

By this time, Fahad had also apparently forged a close relationship with Farmaajo, a dull bureaucrat from Buffalo, New York, who he lobbied Hassan Sheikh to appoint as prime minister. Farmaajo had previously served a 6-month stint as prime minister under the previous president, Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed. Hassan sagely ignored Fahad’s advice, offering him instead the Ministry of Ports and Maritime Transport. By then, Fahad already had his sights set on NISA or, as a consolation prize, the Ministry of Internal Security, and he refused the position on offer. Some members of Hassan Sheikh’s entourage, however, aver that a profound clash of ideologies contributed to this parting of the ways.

Fahad returned to Qatar where, around 2014, he was assigned to Al-Jazeera’s Centre for Studies, an independent research institution that has earned a reputation for being, inter alia, a forum for reflection and exchange between various international Islamist movements. But by 2016 Fahad was back in the maelstrom of Somali politics, this time managing Farmaajo’s presidential campaign. Fahad not only shared his candidate’s authoritarian instincts, but he also treated Farmaajo like a kinsman, since his late stepfather had also been a member of Farmaajo’s Marehan clan. Farmaajo was not an Islamist, but from Fahad’s perspective, this rendered his candidate even more useful. During his studies abroad and exposure to members of other Islamist groups, Fahad had apparently internalised a practice more commonly associated with Shi’a Islam: taqqiya – the use of deception and dissimulation in defence of the faith, which Sunni jihadists have pragmatically appropriated in recent decades. Farmaajo’s secular profile, his ultranationalist populism, and his American passport, complemented by an entourage of technocratic cabinet ministers from the diaspora with Western accents and stylish suits, would help to camouflage Fahad’s real ambition: an Islamist coup.

In February 2017, through a combination of shrewd electioneering and injections of cash from Doha, Fahad helped steer Farmaajo to victory and was rewarded with the post of Chief of Staff at the Presidency. Having finally ascended to the apex of national power, Fahad wasted no time in impelling the appointment of former Al-Itihaad militants – now re-branded as Al-I’tisaam – to key positions, both formal and informal, in government. Since the FGS had virtually no revenue and Fahad held Qatar’s purse strings, Farmaajo acquiesced to his recommendations.

Over the next few years, Fahad succeeded in placing dozens of erstwhile jihadists in key positions throughout the federal administration and security services. Among them were the Deputy Chief of Staff at the Presidency, the Minister of Agriculture, a state minister in the Office of the Prime Minister, the State Ministers of Foreign Affairs and Finance, and at least five senior officials at NISA: a Chief of Staff, Deputy DG, and the directors of Cybersecurity, Counterintelligence, and Foreign Intelligence (subsequently appointed Deputy Ambassador to Qatar). Other members of the group served unofficially, both inside and outside Somalia, as promoters, couriers, financiers, online activists, and informal emissaries.

At the same time, Fahad began mobilising Al-I’tisaam networks across the region, including a powerful lobby of Salafi imams and businessmen in neighbouring Kenya. Many of these religious leaders were based in the largely Somali-inhabited enclave of Eastleigh in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, and had been active supporters of Al-Itihaad in the 1990s. Congregating mainly at a prominent mosque on 6th street, they held regular fund raisers for the jihadists and some of their most prominent activists were killed or captured fighting alongside Al-Itihaad in Somalia.

In October 2017, an Al-Shabaab suicide bombing in Mogadishu left more than five hundred people dead and thousands wounded. The disaster prompted an outpouring of sympathy and support from Somali communities worldwide, including the well-established and increasingly influential Salafi constituency in Kenya that had previously invested in Al-Itihaad. A high-level delegation was dispatched from Nairobi to Mogadishu to deliver their contribution for victims of the bombing.

Fahad seized upon the arrival of such prominent Kenyan-Somali imams and Al-Itihaad alumni for his own, ulterior motives: since the late 2000s, relations between Al-Itihaad’s two main successors – Al-I’tisaam and Al-Shabaab – had been strained nearly to the breaking point by public spats and mutual betrayal. Fahad saw not just an opportunity for reconciliation, but also to establish himself as an Islamist kingpin, and reportedly arranged a meeting between them. The initial encounter was successful, and a follow-up conference was convened in early 2018 in Kismayo.

During his studies abroad and exposure to members of other Islamist groups, Fahad had apparently internalised a practice more commonly associated with Shi’a Islam: taqqiya – the use of deception and dissimulation in defence of the faith, which Sunni jihadists have pragmatically appropriated in recent decades.

According to Somali media reports at the time, the meetings produced plans for the two groups to infiltrate Somali government institutions on a large scale, especially the security sector and judiciary. Al-Shabaab sought the integration of Al-Shabaab forces into FGS security forces, together with their weapons, and the departure of AMISOM. An as interim measure, they proposed that forces from Turkey and other Muslim countries could be deployed to supervise the process of integration. A committee was duly established to oversee the recruitment of former militants for training and insertion into the SNA and NISA.

The meetings also supported the establishment of ‘Popular Defence Forces’ (Ciidanka Difaaca Shacbiga ah), or PDF, to absorb urban youth and low-level Al-Shabaab fighters. Upon completion of training, these units would initially reinforce security at Villa Somalia and then gradually be expanded across in Mogadishu. However, the PDF never officially got off the ground and was eventually subsumed by Villa Somalia’s Xoogga Wadaniyiinta youth militia.

Beyond these security arrangements, Fahad briefed the participants that he had arranged an agreement between the FGS and an Islamic university in Kenya, bankrolled by Qatar, to train the Somali judiciary and Ulema (Islamic scholars). Not coincidentally, the university’s chancellor was a prominent Salafi scholar, businessman and former spokesman for Al-Itihaad.

Fahad’s aspirations for the consolidation of Al-Itihaad’s alumni under the umbrella of the FGS were gaining momentum. But in November 2019, he overplayed his hand, triggering a backlash from Somali Sufis. Somalis have traditionally followed the Shafi’i school of Islamic law, guided by several dominant Sufi turuuq, or sects. Despite the aggressive encroachment of exogenous Salafi movements, many Somalis still treasure their Sufi beliefs and practices. Fahad had invited to Mogadishu Sheikh Mohamed Abdi Umal, a prominent Kenyan cleric and businessman whom many consider to be Al-I’tisaam’s spiritual guide. The purpose of Umal’s visit was to donate some US$330,000 that he and his followers had raised for victims of flooding in Hiiraan region, and Fahad planned a lavish ceremony in his honour.

No one disputed the worthiness of the cause for which Sheikh Umal had raised the funds, but the high-profile reception planned for him by Villa Somalia did not sit well with Somali Sufis, who seized the moment to protest what they perceived as an alliance between Villa Somalia and Al-I’tisaam. The militant Sufi ASWJ interpreted Villa Somalia’s public embrace of a prominent Salafi imam as confirmation of Al-I’tisaam’s status as the de facto ruling party in Villa Somalia and, by extension, as undeclared custodian of the state religion. Sheikh Abdulqadir Soomow, a leader of the ASWJ and spokesman for the national Ulema Council, angrily charged Umal with inciting hatred against Sufis and their beliefs, promoting the rise of the “Kharijites” (a pejorative term for extremists like Al-Shabaab), and of “killing many people with his words.” Umal defended himself against the allegations, but his visit was hastily downgraded to a low-key affair, hosted in a hotel conference room near Mogadishu’s airport.

A serious clash between Sufis and Salafis had been avoided, but the episode foreshadowed a much bloodier reckoning between ASWJ and Villa Somalia less than two years later.

Farmaajo’s Extension, Fahad’s Second Term

In February 2021, having successfully stolen the elections in SWS, Hirshabelle and Galmudug, Farmaajo plotted another coup: stealing his own re-election. Despite having had four years to prepare the ground for federal elections, the Nabad iyo Nolol (‘Peace and Life’) government reached the end of its term – by design – utterly unprepared. For more than three years, Farmaajo had promised Somalis and international partners alike that he would deliver one-person one-vote (OPOV) elections for the next parliament, which would in turn elect the next president.

OPOV had always been a pipe dream, albeit one that Western diplomats enthusiastically subscribed to and, in many cases, oversold to their respective capitals. Not only did insecurity prohibit such an exercise and the federal government manifestly lacked the capacity to pull it off, but even more problematic was the fact that with less than one year remaining in Farmaajo’s term, there was no consensus between political stakeholders, including the FMS and the political opposition, on the electoral model that Villa Somalia was proposing.

Moreover, rushing into a hastily concocted, profoundly contested electoral process would be extremely dangerous: by scrapping the longstanding “4.5 formula” of clan-based power sharing, it would create winners and losers across the country. No one had bothered to do the math about which clan constituencies stood to win or lose most, or by how much. The risk of large parts of the population rejecting the electoral results, either because they distrusted an opaque process or because they felt unfairly deprived of representation, was extremely high.

The cabal in Villa Somalia was well aware of these considerations and was counting on the collapse of electoral preparations to buy them a term extension of at least two years to deliver on their OPOV commitment. But when they finally showed their hand and tabled the proposed extension in parliament in early April 2021, the opposition was infuriated and fighting erupted in the streets of Mogadishu. More than a hundred thousand people were displaced by the fighting, as the army fragmented along clan lines and opposition forces swiftly gained the upper hand. Faced by the prospect of being evicted from the presidency at gunpoint, Farmaajo reluctantly abandoned the scheme.

Seven months later, Farmaajo is nevertheless comfortably ensconced in Villa Somalia and Fahad’s plan to hijack the election is inching forward through iterative bargaining over excruciatingly esoteric electoral procedures. Although an “election” of some kind will almost certainly take place before Farmaajo reaches the benchmark of his coveted two-year extension, there is a clear and present danger that the Islamist ecosystem nurtured by Fahad Yasin will return to power in Villa Somalia – whether under Farmaajo’s leadership or another candidate of Fahad’s choosing.

The Talibanisation of Somalia

Any continuity of Fahad’s influence in Villa Somalia, with or without Farmaajo, would be disastrous for Somalia. It is increasingly clear what Fahad, his party and his patrons intend for the country: a process of staged negotiations between the federal government and Al-Shabaab, facilitated largely by Qatar and culminating in the ‘Talibanisation’ of Somalia. Notwithstanding the significant cultural and ideological differences between the Taliban and Al-Itihaad, the cynical abandonment of Somali aspirations for some form of liberal democracy in favour of an autocratic, absolutist theocracy would be no less treacherous or traumatic than it was for Kabul.

For several years, Qatar has been promoting the notion of dialogue between the FGS and Al-Shabaab as a way of winding down the insurgency. This would likely entail the opening of an Al-Shabaab office in Qatar, some preliminary proximity talks between the parties, followed by eventual face-to-face negotiations. Many Western governments are keenly interested in this possibility: the fight against Al-Shabaab will soon enter its third decade and the jihadists are stronger than ever. As every security analyst is taught, the dismantling of insurgencies and terrorist groups inevitably involves some form of negotiation. Force alone cannot prevail.

Villa Somalia has disingenuously reinforced that argument under Farmaajo’s leadership, not by trying to fight and failing, but by not really trying at all. The FGS has spent the past four years waging a war on federalism, on political pluralism and on democratic norms, but not on Al-Shabaab. The largest single offensive military operation undertaken since 2017 was an all-out assault against ASWJ, at Guri’el in Galmudug region in October 2021 that left at least 120 people dead and hundreds more wounded. Al-Shabaab’s nearby stronghold at Eel Buur, to the southeast, was, as ever, left in peace.

Guri’el was arguably the bloodiest battle in Somalia since Kenyan troops were overrun at El Adde, only it wasn’t waged against the jihadists. On the contrary, Al-I’tisaam clerics rushed to defend the government’s onslaught against Al-Shabaab’s sworn Sufi enemies: Sheikh Bashir Salaad, Al-I’tisaam’s senior cleric in Mogadishu and Chairman of the Ulema Council, equivocally equated ASWJ with Al-Shabaab, while Fahad’s old mentor, Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys (under comfortable “house arrest” in Villa Somalia) praised Al-Shabaab for being monotheists, in contrast with ASWJ’s “polytheist idolaters”.

Such sectarian hyperbole also helps to explain why Villa Somalia has been loath to share external support, and especially security assistance, with the FMS. Jubaland and Puntland would, for certain, have put such resources to good use combating Al-Shabaab. Even the other FMS, despite their political affiliations with the FGS, would have found it hard to prevent locally recruited Daraawiish forces from taking the fight to Al-Shabaab on their home turf. Even Galmudug’s own Daraawiish, operating essentially as a community defence force, engaged in several pitched battles against Al-Shabaab in the months prior to Guri’el– without the support of the FGS. Villa Somalia declines to devolve combat capabilities to the FMS, not – as FGS leaders like to repeat – simply because they might turn against Mogadishu, but because they would almost certainly employ them against Al-Shabaab.

By the same token, Farmaajo’s deliberate failure to advance the constitutional review process, and stunting of the development of a functional federation, as well as forsaking of any pretext of an electoral system, all serve to strengthen Al-Shabaab’s hand at a future bargaining table. Prior agreement between the FGS and FMS on these vital issues, enshrining them in a completed constitution and complementary legislation, would leave little space to accommodate Al-Shabaab’s demands. Entering a dialogue with these matters unresolved would award Al-Shabaab carte blanche to re-negotiate all aspects of the state building process.

Bringing Al-Shabaab into government would also solve another wicked problem that many Western governments feel strongly about: AMISOM. Integrating jihadist fighters into the Somali security sector would obviate the need for an international peace enforcement operation. Bilateral train-and-equip missions for Somali security forces might continue far into the future, but the enormous cost and commitment required to sustain the AU mission would finally come to an end.

Since the late 2000s, relations between Al-Itihaad’s two main successors – Al-I’tisaam and Al-Shabaab – had been strained nearly to the breaking point by public spats and mutual betrayal. Fahad saw not just an opportunity for reconciliation, but also to establish himself as an Islamist kingpin

As long as Fahad holds the reins of power in Villa Somalia, negotiations with Al-Shabaab would consign Somalia to one-party rule under a reunified Al-Itihaad: a post-jihadist state in the Horn of Africa, Afghanistan on the Gulf of Aden. That might sit well with some donor nations, but it is far less clear how it would be received by the Somali population. Although many have adopted Salafi beliefs and practices in the private and social spheres, the prospect of a totalitarian political system underpinned by ideological intolerance and policed by religious zealots is another proposition entirely.

Even more importantly, from the callow perspective of those who advocate stability as an end in itself, is whether such a dispensation would in fact bring enduring stability to Somalia and the region. None of Somalia’s neighbours is likely to be at ease sharing borders with a post-jihadist government that espouses radically different geopolitical perspectives and priorities. The level of discomfort would likely be even higher in those nations that host well-established chapters of Al-I’tisaam, chiefly Kenya and Ethiopia.

More distant foreign powers would likely share such concerns: the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt are all deeply hostile to Islamist political movements and especially to those that carry Al-Sahwa’s DNA. Cosy relations between Mogadishu, Doha, and Ankara would only heighten apprehension in Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, and Cairo – at least as long as the two camps remain strategic competitors across north Africa and much of the Middle East.

Conviction Not for Crime, but for Heresy

I’m not entirely sure what my FGS accusers were hoping to achieve, but life has changed little since I became a convicted felon. I’m still at liberty, my assets haven’t been frozen, and I face no travel ban. My family hasn’t spurned me, and I’ve been allowed to keep my old job. My colleagues and friends are sympathetic, and I’ve gained a few new ones on social media. The support and solidarity I’ve received from unexpected quarters has given me a small taste of that special kind of sympathy usually reserved for political prisoners — mercifully without actually having to go to prison.

If prosecution was intended to muzzle me or my colleagues, it has clearly backfired: the preceding pages offer a foretaste of the story that Villa Somalia had hoped would never be told. None of this information constitutes a national secret or is otherwise protected by law. Much of it has already been reported – albeit in disparate, disconnected fragments – by reputable Somali and international media houses. Few politically conscious Somalis, whether they support or oppose the FGS, will find any of it new or surprising. As an analyst, my only crime has been to arrange these pixels of information into what I hope is a consistent and compelling portrait: to organise the facts and present them in a way that is relevant to policy makers, both Somali and foreign, and that helps to ensure that decisions on the way forward – especially with respect to engaging Al-Shabaab — are based on evidence and reason – not sloth and expediency.

Like any other members of my audience, the current leaders of Somalia’s federal government – whether they hold those positions legitimately or not — may choose not to read what I have written. They may read it and disagree, and they might even decide to respond. They may try to sue me, under applicable laws and in an independent court. But to concoct a show trial, to lay charges without evidence or right of reply, and to convict me in absentia and ultra vires? These are the hallmarks of a totalitarian regime with a hidden agenda.

Such intrigues say far more about the cabal currently squatting in Villa Somalia than they do about me or the organisation I work with. And they appear to confirm, no doubt inadvertently, the conclusions I have reached in this article: that Somalia’s state building process has been hijacked by an ideological faction well practised in the arts of deceit and dissimulation – taqqiya.

The only threat to Somalia’s national security at issue here is the one that Farmaajo, Fahad, their accomplices and enablers collectively pose to the nation’s future: a creeping coup orchestrated by an absolutist clique that brooks no dissent or opposition, and whose dystopian theological worldview construes the truth, when it is inconvenient or inconsistent with their narrative, to be not simply a crime, but heresy.

Support The Elephant.

The Elephant is helping to build a truly public platform, while producing consistent, quality investigations, opinions and analysis. The Elephant cannot survive and grow without your participation. Now, more than ever, it is vital for The Elephant to reach as many people as possible.

Your support helps protect The Elephant's independence and it means we can continue keeping the democratic space free, open and robust. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our collective future.

Long Reads

How a Zimbabwe Tycoon Made a Fortune From a Trafigura Partnership and Spiralling National Debt

Kudakwashe Tagwirei, who is close to Zimbabwe’s president and his inner circle, leveraged his privileged access to fuel and mining markets to strike a lucrative partnership with commodities giant Trafigura. Sanctioned by the U.S. and U.K. for corruption, Tagwirei continued to do business by relocating his network to Mauritius.

- Tagwirei has earned at least $100 million in fees from a partnership with Swiss-based Trafigura. Together, they have profited extensively by dominating Zimbabwe’s fuel market since 2013.

- Trafigura quietly extended $1 billion in loans to the Zimbabwean government, at exorbitant interest rates.

- As controversy grew, Tagwirei moved his business network offshore to Mauritius, where he secured a new near-monopoly fuel deal with the government. He is still active in mining and fuel deals in Zimbabwe.

- Government officials appear on key company records and Tagwirei’s own correspondence, indicating that there might be more powerful people behind the network

When Zimbabwe’s long-ruling strongman Robert Mugabe was forced to resign in 2017, his downfall was greeted by jubilant crowds hopeful that decades of misrule and corruption were finally coming to an end.

His successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, set off on an international tour to declare Zimbabwe “open for business.” Sporting a scarf knitted in the five colors of the country’s flag, he assured world leaders that all that was needed to jumpstart Zimbabwe’s moribund economy was new leadership and an infusion of foreign investment.

Emmerson Mnangagwa in Moscow in 2019. Credit: ITAR-TASS News Agency/Alamy Live News

Four years on, Mnangagwa’s promised “New Dawn” has not arrived. Instead, Zimbabwe’s economy remains in tatters. Public debt — much of it illegally accrued — has ballooned, a lack of foreign currency and fuel shortages continue to cripple the economy, and the value of Zimbabwe’s local currency has plummeted.

The turmoil has not been without its winners, though. One man in particular has prospered from the state’s largesse: Kudakwashe Tagwirei, a tycoon known locally as “Queen Bee” because of his vast economic influence.

Under Mnangagwa’s reign, the businessman came to dominate Zimbabwe’s fuel, platinum, and gold sectors. Benefitting from opaquely awarded government contracts worth billions of dollars and preferential access to minerals as well as scarce foreign currency, Tagwirei’s network also got huge state loans he used to enrich himself while indebting the Zimbabwean public.

Those came from a surprising source that proved a key player in Tagiwirei’s network: Zimbabwe’s central bank. At least $3 billion in treasury bills issued by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe — which may have had no legal authority to do so — were awarded to Tagwirei’s group between 2017 and 2019, a parliamentary report said, with the group then funneling the windfall into a massive expansion that included a mining acquisition spree at bargain bin prices. As the country’s currency crashed, Tagwirei’s fortunes soared.

But it’s not clear if Tagwirei is the sole, or even the main beneficiary of this largesse. The presence of a handful of state officials in some of the network structures imply he is also a proxy for others. Since 2019 the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s governor, John Mangudya, was even named in Tagwirei-connected corporate trusts. Insiders say Tagwirei is close both to President Manangagwa and his deputy General Constantino Chiwenga.

Kudakwashe Tagwirei. Credit: Jekesai Njikizana/Getty

Besides the government, one foreign company also played a critical role in Tagwirei’s rise over nearly a decade: Swiss-headquartered commodity trader Trafigura Group Pte Ltd. Trafigura formed a joint venture with Tagwirei as far back as 2013 that gave the company priority access to the country’s fuel infrastructure and supply business through Tagwirei’s local influence. Tagwirei’s links to Trafigura, his business successes at home, and U.S. and U.K. sanctions against him have attracted critical press coverage in recent months.

Now, using contracts, invoices and email correspondence between Tagwirei’s network, former Trafigura officials involved in the joint venture, and government officials, OCCRP can reveal new details of how Trafigura and Tagwirei’s partnership worked.

OCCRP learned that Trafigura paid Tagwirei at least $100 million in fees through early 2018 for his help in creating a dominant position in the Zimbabwean fuel market. Their joint venture, initially called Sakunda Supplies and later renamed Trafigura Zimbabwe, would do this by advancing massive cash prepayments and fuel to the government in exchange for significant control over the Zimbabwean market and priority use of the state’s fuel pipelines.

“Only one set of interests controls the fuel: Trafigura and Tagwirei,” Zimbabwe’s former finance minister, Tendai Biti, told OCCRP.

The joint venture would last until December 2019, when Trafigura bought out the soon-to-be-sanctioned Tagwirei.

Only one set of interests controls the fuel: Trafigura and Tagwirei. ~ Tendai Biti, Former Zimbabwean Finance Minister

But the partnership may have been too lucrative to discontinue.

Instead, Trafigura sought to continue its relationship with Tagwirei via Sotic International Ltd., a new company that he had set up in Mauritius, and associated shell companies fronted by South Africa-based directors, several of whom were former Trafigura employees.

In an email to OCCRP, Tagwirei said, “Some of the questions you raise are an embarrassing demonstration of an apparent lack of understanding of the issues you purport to investigate … I unequivocally deny all the accusations and allegations you are making against me in your email.”

Wilfred Mutakeni, head of Zimbabwe’s National Oil Infrastructure Company, the regulatory agency that provided the joint venture its dominant rights, did not respond to a request for comment.

Trafigura’s offices in Johannesburg. Credit: Trafigura Pictures/CC BY-ND 2.0

In a response to OCCRP, a Trafigura spokesperson said, “Trafigura exited our business relationships with Mr Tagwirei in December 2019, prior to US sanctions being imposed, through the purchase of [[Tagwirei’s stake]]. All commercial arrangements are conducted in full compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Trafigura is one of a number of suppliers to Zimbabwe, South Africa and Mozambique. There is no exclusivity or market dominance.”

Trafigura said OCCRP’s details were “factually inaccurate,” but declined to answer specific questions about advance payments, payments to Tagwirei, or the purchase price of his shares. The company said “commercial arrangements are commercially sensitive and as such, are confidential.”

Preferential Contracts

On Harare’s bustling streets, where centuries-old churches compete for space with modern high-rises, one building stands above its neighbors. Century Towers, an imposing glass structure perched next to one of the capital’s main thoroughfares, houses the main office of Tagwirei’s holding company for his share of the joint venture, Sakunda Holdings Private Ltd, on several floors – including the 15th. One floor below are the offices of Zimbabwe’s energy regulator.

Century Towers in Harare. Credit: Christopher Scott/Alamy Stock Photo

This proximity hints at the closeness critics say allowed Tagwirei to make a fortune from preferential government contracts.

Tagwirei originally signed a contract in 2011 with the National Oil Infrastructure Company of Zimbabwe (NOIC) that gave him many of the rights he would later share with Trafigura.

In July 2013, Tagwirei and his companies Sakunda Holdings and Sakunda Trading agreed to sell access to their existing petroleum contract with NOIC to Trafigura, affording it 49 percent of the shares of a new joint venture.

They agreed to form Sakunda Supplies, based in Zimbabwe, which would hand Trafigura a host of benefits, including preferential access to the crucial Beira pipeline from Mozambique. NOIC, which had initially awarded Sakunda Holdings the deal in 2011, confirmed in a 2018 letter that Trafigura was entitled to all the benefits enjoyed by Sakunda.

In return, a service agreement between Trafigura and Tagwirei, ratified in 2014, granted a $12 million signing bonus and a further $12 million for Tagwirei when NOIC provided access to their pipeline and the project launched.

On paper, Tagwirei’s role in the new company was to provide his “significant market experience, network and contact base.” But an insider said Trafigura was simply paying for Tagwirei’s access to powerful figures in Zimbabwe.

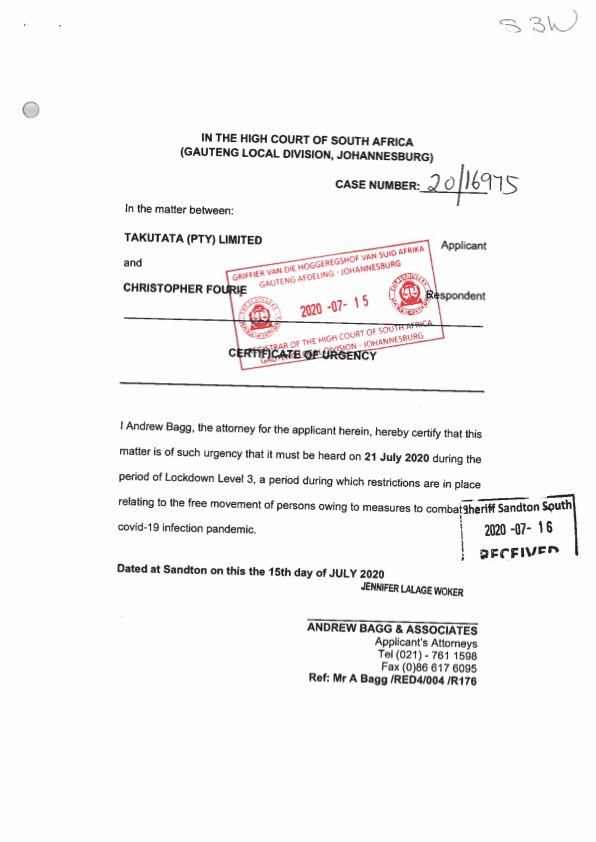

“Trafigura provided everything: the capital, the fuel, the expertise,” said former Trafigura Zimbabwe director Christopher Fourie.

“Sakunda [Holdings] – by which I mean just a few front guys under Tagwirei – were the political connections to the reserve bank, the president. Their aim was to keep profits low in Zimbabwean operations and pay Tagwirei offshore,” said Fourie, who later served as CEO and shareholder of another one of Tagwirei’s companies.

“A Captive Market”

In November 2013, just a few months after the joint venture was formed, Trafigura made the first in a series of cash advances to the Zimbabwean government’s pipeline operator.

Confidential documents show that, over the course of the next six years, Trafigura and its joint venture came up with at least $1 billion in prepayments to NOIC.

In exchange, Trafigura Zimbabwe got priority access to Zimbabwe’s key oil pipeline. In 2018 the joint venture paid what appears to be a favorable price of $1.24 per barrel moved. It costs about $2.19 a barrel to transport oil through the Feruka pipeline from Beira in Mozambique to Harare. Meanwhile Trafigura Zimbabwe earned up to 40 percent gross profits for the supply of oil — all with sparse competition and all negotiated opaquely.

A December 2018 amendment of the joint venture agreement sets out credit facilities made available by Trafigura’s head office to the government of Zimbabwe, including loans of $50 million and $13.6 million.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe guaranteed NOIC’s repayments of the advances, which were to be made in foreign currency. The interest if NOIC were to fail to pay its monthly obligation was a hefty 16 percent, which was to be compounded against the full outstanding sum, repayable immediately and in full. Zimbabwe is chronically short of foreign currency and heavily in debt, and has struggled to repay its obligations.

“If these terms are correct, 16 percent is a very high interest rate,” said Natasha White, an oil researcher at U.K.-based advocacy group Global Witness. “High interest rates are usually conditions to buffer the risk of non-payment (and are where the traders make their money on these deals).”

Commodity trader prepayments to states and state-backed entities often feature deals based on political connections and lack a tender process, according to White. “This raises serious red flags regarding the government’s decision to enter into them,” she said.

The 2018 agreement specified a base monthly repayment of $5 million until April 2019 and $3.2 million from May 2019 until the total sum of $63.6 million was fully repaid. By the time of the December 2018 agreement, NOIC had received almost $400 million in advances from Trafigura itself, while the total advances of both Trafigura and the joint venture were close to $1 billion, according to an internal Trafigura Zimbabwe document.

Zimbabwe’s central bank governor John Mangudya denied this to OCCRP, claiming the “outstanding balance by 2018 was only $130 million.” He declined to provide term sheets, stating that loan agreements are confidential.

Internal Trafigura Zimbabwe communications underscored the value of the company’s pre-financing of Mnangagwa’s government: “[Trafigura Zimbabwe] expects to maintain its pre-financing arrangements going forward,” as these allowed for the company to maintain “its role as a price leader,” as well as its dominant market position.

According to an internal 2018 company report, Trafigura Zimbabwe was supplying up to 60 percent of Zimbabwe’s required monthly fuel imports. Tendai Biti, the former finance minister and head of the parliamentary committee investigating Tagwirei’s company Sakunda, said the joint venture has supplied more than 80 percent of the country’s total fuel supply. Trafigura Zimbabwe internally labeled their deal as a “captive market.”

In an email to OCCRP, Trafigura said “we do not recognise” OCCRP’s figures for the prepayments, but would not discuss pre-financing arrangements.

“From time to time, Trafigura has agreed credit terms related to the supply of fuel to customers in Zimbabwe and subject to usual commercial terms and confidentiality,” a Trafigura spokesperson said.

Mangudya told OCCRP, “All strategic imports are a priority to the Bank,” and that Trafigura provided “a $390 million fuel line of credit.”

A Potent Partnership

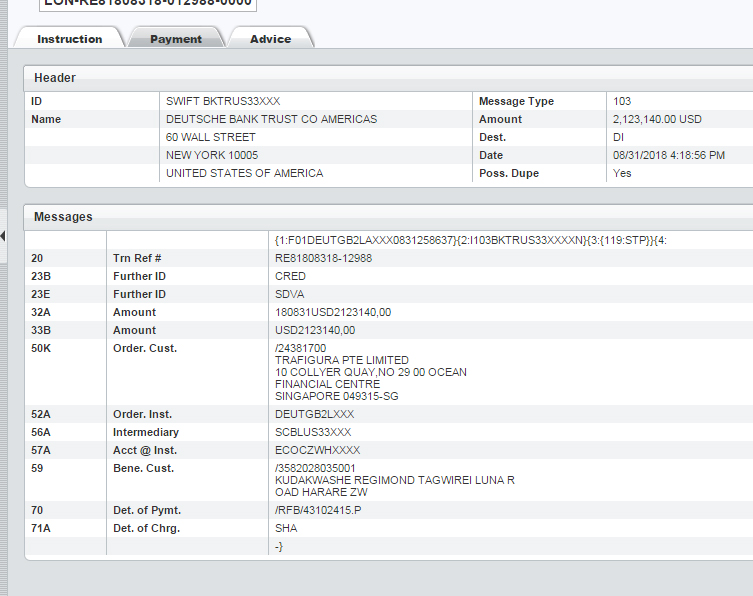

At the heart of the deal was the relationship between Trafigura and Tagwirei, who was paid over $100 million in fees through January 2018, with more than 40 percent of that money going directly to his Swiss and other offshore accounts, according to documents seen by OCCRP.

The payments made to Tagwirei raise a red flag, according to Global Witness’s Natasha White.

“Red flags include the personal involvement of politically exposed individuals in such deals. It would be extremely concerning if payments have been made into a personal account of Tagwirei by Trafigura, whether or not he was sanctioned at the time,” she said.

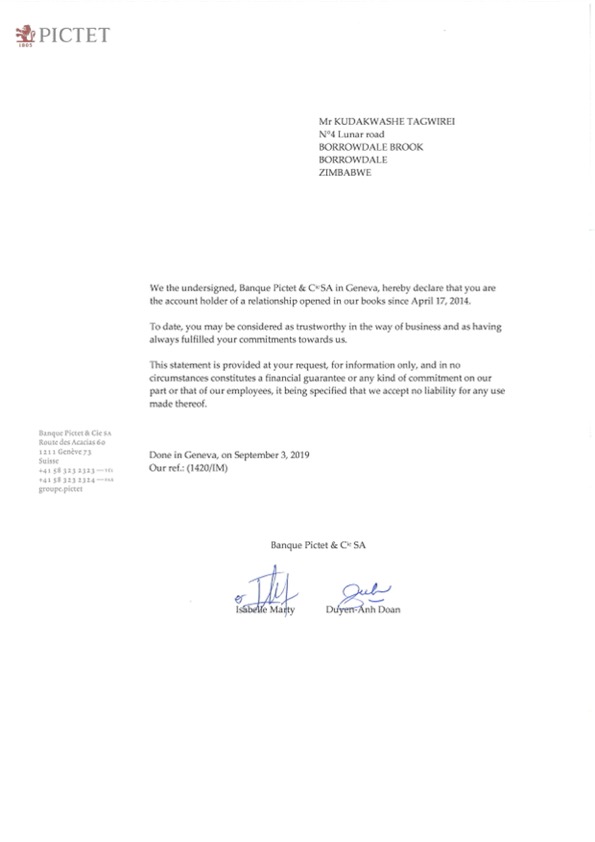

Reporters obtained internal emails discussing Tagwirei’s finances, which referenced an offshore account in Switzerland. He opened an account at Geneva-based Pictet Bank on April 17, 2014, about the same time he began to earn fees from his deal with Trafigura, according to a document signed by a bank official.

In addition to fees, Tagwirei received funds from Trafigura for “pipeline gain,” mineral deals, and project management, according to invoices obtained by OCCRP. He was paid in U.S. dollars through Trafigura accounts, including some held at New York-based Deutsche Bank Trust Company Americas.

Notably, Tagiwirei’s name may have been concealed from some payments based on invoices seen by OCCRP, due to correspondent banking practices. For transfers in the U.S., the recipient can be identified via the bank names and numbers of African banks where Tagwirei had an account, such as Zimbabwe’s Ecobank. These banks have correspondent links to U.S. banks to allow them to access U.S. dollars; Zimbabwe’s Ecobank, for example, is hosted by New York-based Standard Chartered Bank. By naming only the bank account number on the transfer rather than the account holder, Tagwirei’s name could have been omitted from compliance checks in the U.S.

Trafigura publicly cut ties with Tagwirei just before the businessman was sanctioned by the U.S. in August 2020. The U.S. said the move was made in response to the $3 billion allegedly misappropriated by his companies in connection with a flagship farming program called Command Agriculture.

Following years of hyperinflation and land grabs under Mugabe, then a devastating 2016 drought, Zimbabwe introduced the Command Agriculture program to bolster food security. The Central Bank funded the program using Treasury Bills — a form of short-dated, government-backed security — that ended up creating billions of dollars of debt and draining foreign exchange reserves. Taxpayers footed the bill.

Tagwirei’s Sakunda Holdings was awarded a $3 billion contract to supply fuel to the Command Agriculture scheme without tender, according to the U.S. government. In March 2020, the company submitted documents to a Zimbabwean parliamentary committee that showed it charged fees of more than 30 percent on a $1 billion contract.

Sakunda was granted so-called T-Bills as a kind of collateral in case farmers in the program failed to repay their credit lines. Tagwirei was then allowed to redeem the debt at a one-to-one ratio with the U.S. dollar rather than, as normal, against the lower value of Zimbabwean bond notes.

Rather than waiting to see how Command Agriculture played out, Sakunda quickly liquidated some Treasury Bills in Zimbabwe and sold others to Zimbabwean commercial banks at a discount. “Sakunda’s deal with the government crashed the currency in July 2019 when they cashed in some Treasury Bills directly with the central bank,” said Biti.

The International Monetary Fund confirmed that 99 percent of agricultural loans under the programme defaulted.

In August 2020 the U.S. sanctioned Tagwirei and Sakunda for corruption. The U.K. followed suit a year later, saying that Sakunda “redeemed Government of Zimbabwe Treasury Bills at up to ten times their official value.”

In December 2019, Trafigura announced it had bought out Sakunda’s 51 percent stake in Trafigura Zimbabwe without disclosing the amount it had paid for the shares. “This will bring improved clarity on Trafigura’s activities in the country,” the company said in a statement. Documents obtained by OCCRP indicate Tagwirei’s shares were worth “449 million” as of November 2018, but the currency is unclear.

Doing Business From Mauritius

Even before Tagwirei and Sakunda were sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury in 2020, plans were being laid to establish a new, clean corporate structure that could be used to continue the deal using the Mauritius-based Sotic International and other associated offshore companies.

Trafigura immediately started to do business with this new Mauritius network.

Excel sheets and invoices obtained by OCCRP show Trafigura contracted with and sold fuel to Sotic and its subsidiaries from 2018 onwards.

A 2019 deal between Sotic and NOIC signed by Mangudya, the central bank governor, as a guarantor for NOIC, allowed Sotic to effectively maintain control of the NOIC pipeline. The deal ensured the pipeline existed “solely at Sotic’s benefit” according to an internal email, and included “first rank priority pumping for all Sotic product.”

In an email to OCCRP, Mangudya claimed the pre-financing arrangement “was never consummated” and therefore there was “nothing to publicise.” However, a document obtained by OCCRP dated September 2019 shows NOIC asking for the payment from Sotic it was owed based on the deal’s “prepayment facility” guaranteed by the central bank.

Business as Usual

The fuel deal with Tagwirei’s new Sotic company is similar to the arrangement that existed with Sakunda until it was sanctioned by the U.S.

Prepayments worth $1.2 billion were again offered to NOIC, according to a contract between Sotic and Zimbabwe’s central bank governor on behalf of NOIC. The agreement allowed Sotic to effectively maintain control of the NOIC pipeline, ensuring it got “first rank priority pumping,” according to the term sheet.

Under the Sotic-drafted contract terms, Sotic would source foreign exchange of up to $600 million on behalf of the Reserve Bank, with the rest in RTGS currency, a local pseudo-currency that doesn’t trade on international markets and whose exchange rate is artificially set by the government. Minutes of a meeting reveal that $100 to $200 million would be provided by traders like Trafigura over a period of eight years after the initial drawdown.

The guarantor of the agreement was the Reserve Bank, with bank governor Mangudya listed as the contact person.

However, Sotic appeared to shortchange the country once more. By July 3, 2019, a payment of just 814 million RTGS (worth about $2.2 million) had been deposited by Tagwirei’s team into the Reserve Bank’s account — far short of the huge sums of foreign exchange required by the contract. Almost immediately, Sotic began to default on monthly payments. However, the documents show none of this seems to have affected Sotic’s priority status.

A leaked internal Sotic email provides an insight into how the group of companies artificially inflated the prices of their products.

The email shows that a Sotic subsidiary sold a petroleum-based product to Sotic at $590 per metric tonne. Sotic then proposed to sell the product for $820 per metric tonne to Tagwirei’s Zimbabwean structure, Fossil. The January 2019 email notes: “got these numbers from [Tagwirei]…Think the plan is that Fossil sells to the end consumer at $877…”

By moving the product between companies in their group and increasing the price each time, Tagwirei’s network stood to make an estimated $460,000 extra profit on this deal alone.

Friends in High Places

While Tagwirei is often credited as being the mastermind behind his business successes, correspondence between him and others shows he might be a proxy for political interests.

Tagwirei’s businesses appeared to involve President Mnangagwa, or “HE” (His Excellency), as he was sometimes referred to and other government officials. In private WhatsApp correspondence obtained by OCCRP, Tagwirei claimed to beneficially own 35 percent of Sotic, saying the “government” owned the rest.

In email correspondence obtained by OCCRP about payment for a mining deal, Tagwirei seemed to reference Mnangagwa by saying, “HE wants that money to be paid after I show him the directors, owners of Sotic-Documents.”

By the time Sotic was formed, Tagwirei and his associates understood he was a liability and avoided formally linking the businessman to the new network. Documents show Tagwirei’s company formation agent and administrator of his Mauritius companies described how he had to use his pre-existing relationship with the CEO of Mauritian bank AfrAsia to open an account there for Sotic because of the negative press Tagwirei was getting. The new bank accounts allowed Sotic to hold accounts denominated in U.S. dollars and euros, despite the compliance risks associated with Tagwirei. These accounts allowed the company access to US banks through AfrAsia’s correspondent banking.

As the businesses were shuffled, so were the key figures in the network. Tagwirei took a back seat, at least nominally, and proxies including at least one political figure and several South Africans took up key roles.

As revealed by U.S. anti-corruption group The Sentry, and confirmed in documents and emails from May 2019, Zimbabwe’s central bank governor John Mangudya is named as the legal protector of Lighthouse Trust, a co-owner of Sotic at the time. Lighthouse Trust, in turn, was owned by four beneficiary trusts: Amphion (15%), Norfolk (15%), Leonidas (35%), and Alcaston (35%). Mangudya, once again, served as the protector in all of them.

A legal protector is a person appointed to direct or restrain trustees in relation to their administration of a trust. Neither the government nor the Central Bank have disclosed a business interest in Sotic, so it is not clear why Mangudya would play such a role in Sotic-related trusts.

In an email to OCCRP, Mangudya claimed he was not part of the trust structures and was not aware his name had been listed as their legal protector. When asked directly if Tagwirei fraudulently used his name, he declined to respond further. Sotic’s former CEO confirmed to OCCRP that the instruction to include Mangudya came from Tagwirei.

Ronelle Sinclair and Jozef Behr – Sotic’s former head of finance and Trafigura’s former head of Africa trading – were both trustees in the trusts that held part of Sotic.

Former Sotic CEO and shareholder Christopher Fourie said it was clear that Tagwirei retained control over Sotic. Whenever he raised legal or financial concerns, employees invoked Tagwirei.

In an email to OCCRP, former Sotic CEO David Brown claimed he had no involvement in transactions prior to June 2020 and therefore could not comment on irregularities pointed out by reporters. “These matters are largely driven by a disgruntled employee who is part of a history that might well have taken place,” he added.

He also denied knowledge of Tagwirei’s ownership of Sotic group assets prior to that date but added, “Mr Tagwirei is a very prominent business man in Zimbabwe and …an official advisor to Government and being as Government are shareholders in the mining assets, it is hard not to occasionally cross paths.”

OCCRP provided Brown with evidence, including several hundred emails beginning in 2019, and information on major mining deals. Despite stating in an email to other Sotic staff that “[Tagwirei] has asked that I take a greater role,” Brown denied this to OCCRP, saying, “I was not brought in by Mr Tagwirei.”

A representative for Sincler and Behr said they had resigned all duties and were off the board of Sotic International as of June 2020. “Since then, there has been no further association with the business of Kudukwashe Tagwerei.” She also confirmed Behr and Sinclair work for Suzako. A since-removed website for Suzako listed Behr, Sinclair, and Weber as the company’s executive team as recently as May this year.

Yet Suzako was part of Sotic’s network, according to court records. When Sotic CEO at the time David Brown filed an application in South Africa’s high court to stop his predecessor Fourie from talking to the press, he included the full structure of Sotic’s corporate network. The application was quickly withdrawn but not before the companies were disclosed. Sukako was clearly listed as a Sotic company.

While everyone seems to be working hard to separate themselves from Tagwirei and his companies, Fourie is a rare voice who acknowledges crimes were committed and has reported them to the South African reserve bank and others.

“They did not care about the law, about financial crimes being committed. All they cared about was seeing that [Tagwirei’s] orders were executed,” Fourie told OCCRP. “I spoke out against them and I am paying the price.”

–

This article was first published by our partner OCCRP.

Long Reads

Cultural Nostalgia: Or How to Exploit Tradition for Political Ends

The fake councils of elders invented by the political class have robbed elders in northern Kenya of their legitimacy. It will take the intervention of professionals and true elders to end this adulteration of traditional institutions.

With devolution, northern Kenya has become an important regional cultural hub, and cultural elders have acquired a new political salience. The resources available to the governors have made the region once again attractive. Important geographical reconnections and essential cultural linkages have been re-established.

These cultural reconnections are happening on a spatial-temporal scale, and old cultures have been revived and given a new role. Contiguous regions hitherto separated by boundaries, state policies and wars are now forging new ways of engaging with each other, Mandera with southwestern Somalia and the Lower Shabelle region, Marsabit with the Yabello region the Borana hails from, and Wajir with southwestern Ethiopia.

The speed with which Mandera governor Ali Roba sent a congratulatory message to Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed Farmaajo when he was elected—before even the Kenyan president—or the meetings between the governor of Marsabit and Ethiopia’s premier, or how a delegation of northeastern politicians “covertly” visited Somalia, are just some of the new developments that have been encouraged by devolution.

With each of these connections, significant shifts are taking place in the region. But of even greater significance is how cultural institutions have been repurposed and given a central role in the north’s electoral politics.

The re-emergence of sultans