Hydraulic binder used in the composition of mortar and concrete

For other uses, see Cement (disambiguation).

Not to be confused with Concrete.

Cement powder in a bag, ready to be mixed with aggregates and water.[1]

Cement powder in a bag, ready to be mixed with aggregates and water.[1]

Cement block construction examples from the Multiplex Manufacturing Company of Toledo, Ohio, in 1905

Cement block construction examples from the Multiplex Manufacturing Company of Toledo, Ohio, in 1905

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel (aggregate) together. Cement mixed with fine aggregate produces mortar for masonry, or with sand and gravel, produces concrete. Concrete is the most widely used material in existence and is behind only water as the planet's most-consumed resource.[2]

Cements used in construction are usually inorganic, often lime- or calcium silicate-based, and are either hydraulic or less commonly non-hydraulic, depending on the ability of the cement to set in the presence of water (see hydraulic and non-hydraulic lime plaster).

Hydraulic cements (e.g., Portland cement) set and become adhesive through a chemical reaction between the dry ingredients and water. The chemical reaction results in mineral hydrates that are not very water-soluble. This allows setting in wet conditions or under water and further protects the hardened material from chemical attack. The chemical process for hydraulic cement was found by ancient Romans who used volcanic ash (pozzolana) with added lime (calcium oxide).

Non-hydraulic cement (less common) does not set in wet conditions or under water. Rather, it sets as it dries and reacts with carbon dioxide in the air. It is resistant to attack by chemicals after setting.

The word "cement" can be traced back to the Ancient Roman term opus caementicium, used to describe masonry resembling modern concrete that was made from crushed rock with burnt lime as binder.[3] The volcanic ash and pulverized brick supplements that were added to the burnt lime, to obtain a hydraulic binder, were later referred to as cementum, cimentum, cäment, and cement. In modern times, organic polymers are sometimes used as cements in concrete.

World production of cement is about 4.4 billion tonnes per year (2021, estimation),[4][5] of which about half is made in China, followed by India and Vietnam.[4][6]

The cement production process is responsible for nearly 8% (2018) of global CO2 emissions,[5] which includes heating raw materials in a cement kiln by fuel combustion and release of CO2 stored in the calcium carbonate (calcination process). Its hydrated products, such as concrete, gradually reabsorb atmospheric CO2 (carbonation process), compensating for approximately 30% of the initial CO2 emissions.[7]

Chemistry

[edit]

Cement materials can be classified into two distinct categories: hydraulic cements and non-hydraulic cements according to their respective setting and hardening mechanisms. Hydraulic cement setting and hardening involves hydration reactions and therefore requires water, while non-hydraulic cements only react with a gas and can directly set under air.

Hydraulic cement

[edit]

Clinker nodules produced by sintering at 1450 °C

Clinker nodules produced by sintering at 1450 °C

By far the most common type of cement is hydraulic cement, which hardens by hydration (when water is added) of the clinker minerals. Hydraulic cements (such as Portland cement) are made of a mixture of silicates and oxides, the four main mineral phases of the clinker, abbreviated in the cement chemist notation, being:

- C3S: alite (3CaO·SiO2);

- C2S: belite (2CaO·SiO2);

- C3A: tricalcium aluminate (3CaO·Al2O3) (historically, and still occasionally, called celite);

- C4AF: brownmillerite (4CaO·Al2O3·Fe2O3).

The silicates are responsible for the cement's mechanical properties — the tricalcium aluminate and brownmillerite are essential for the formation of the liquid phase during the sintering (firing) process of clinker at high temperature in the kiln. The chemistry of these reactions is not completely clear and is still the object of research.[8]

First, the limestone (calcium carbonate) is burned to remove its carbon, producing lime (calcium oxide) in what is known as a calcination reaction. This single chemical reaction is a major emitter of global carbon dioxide emissions.[9]

The lime reacts with silicon dioxide to produce dicalcium silicate and tricalcium silicate.

The lime also reacts with aluminium oxide to form tricalcium aluminate.

In the last step, calcium oxide, aluminium oxide, and ferric oxide react together to form brownmillerite.

Non-hydraulic cement

[edit]

Calcium oxide obtained by thermal decomposition of calcium carbonate at high temperature (above 825 °C).

Calcium oxide obtained by thermal decomposition of calcium carbonate at high temperature (above 825 °C).

A less common form of cement is non-hydraulic cement, such as slaked lime (calcium oxide mixed with water), which hardens by carbonation in contact with carbon dioxide, which is present in the air (~ 412 vol. ppm ≃ 0.04 vol. %). First calcium oxide (lime) is produced from calcium carbonate (limestone or chalk) by calcination at temperatures above 825 °C (1,517 °F) for about 10 hours at atmospheric pressure:

The calcium oxide is then spent (slaked) by mixing it with water to make slaked lime (calcium hydroxide):

Once the excess water is completely evaporated (this process is technically called setting), the carbonation starts:

This reaction is slow, because the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the air is low (~ 0.4 millibar). The carbonation reaction requires that the dry cement be exposed to air, so the slaked lime is a non-hydraulic cement and cannot be used under water. This process is called the lime cycle.

History

[edit]

Perhaps the earliest known occurrence of cement is from twelve million years ago. A deposit of cement was formed after an occurrence of oil shale located adjacent to a bed of limestone burned by natural causes. These ancient deposits were investigated in the 1960s and 1970s.[10]

Alternatives to cement used in antiquity

[edit]

Cement, chemically speaking, is a product that includes lime as the primary binding ingredient, but is far from the first material used for cementation. The Babylonians and Assyrians used bitumen (asphalt or pitch) to bind together burnt brick or alabaster slabs. In Ancient Egypt, stone blocks were cemented together with a mortar made of sand and roughly burnt gypsum (CaSO4 · 2H2O), which is plaster of Paris, which often contained calcium carbonate (CaCO3),[11]

Ancient Greece and Rome

[edit]

Lime (calcium oxide) was used on Crete and by the Ancient Greeks. There is evidence that the Minoans of Crete used crushed potsherds as an artificial pozzolan for hydraulic cement.[11] Nobody knows who first discovered that a combination of hydrated non-hydraulic lime and a pozzolan produces a hydraulic mixture (see also: Pozzolanic reaction), but such concrete was used by the Greeks, specifically the Ancient Macedonians,[12][13] and three centuries later on a large scale by Roman engineers.[14][15][16]

There is... a kind of powder which from natural causes produces astonishing results. It is found in the neighborhood of Baiae and in the country belonging to the towns round about Mount Vesuvius. This substance when mixed with lime and rubble not only lends strength to buildings of other kinds but even when piers of it are constructed in the sea, they set hard underwater.

— Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, Liber II, De Architectura, Chapter VI "Pozzolana" Sec. 1

The Greeks used volcanic tuff from the island of Thera as their pozzolan and the Romans used crushed volcanic ash (activated aluminium silicates) with lime. This mixture could set under water, increasing its resistance to corrosion like rust.[17] The material was called pozzolana from the town of Pozzuoli, west of Naples where volcanic ash was extracted.[18] In the absence of pozzolanic ash, the Romans used powdered brick or pottery as a substitute and they may have used crushed tiles for this purpose before discovering natural sources near Rome.[11] The huge dome of the Pantheon in Rome and the massive Baths of Caracalla are examples of ancient structures made from these concretes, many of which still stand.[19][2] The vast system of Roman aqueducts also made extensive use of hydraulic cement.[20] Roman concrete was rarely used on the outside of buildings. The normal technique was to use brick facing material as the formwork for an infill of mortar mixed with an aggregate of broken pieces of stone, brick, potsherds, recycled chunks of concrete, or other building rubble.[21]

Mesoamerica

[edit]

Lightweight concrete was designed and used for the construction of structural elements by the pre-Columbian builders who lived in a very advanced civilisation in El Tajin near Mexico City, in Mexico. A detailed study of the composition of the aggregate and binder show that the aggregate was pumice and the binder was a pozzolanic cement made with volcanic ash and lime.[22]

Middle Ages

[edit]

Any preservation of this knowledge in literature from the Middle Ages is unknown, but medieval masons and some military engineers actively used hydraulic cement in structures such as canals, fortresses, harbors, and shipbuilding facilities.[23][24] A mixture of lime mortar and aggregate with brick or stone facing material was used in the Eastern Roman Empire as well as in the West into the Gothic period. The German Rhineland continued to use hydraulic mortar throughout the Middle Ages, having local pozzolana deposits called trass.[21]

16th century

[edit]

Tabby is a building material made from oyster shell lime, sand, and whole oyster shells to form a concrete. The Spanish introduced it to the Americas in the sixteenth century.[25]

18th century

[edit]

The technical knowledge for making hydraulic cement was formalized by French and British engineers in the 18th century.[23]

John Smeaton made an important contribution to the development of cements while planning the construction of the third Eddystone Lighthouse (1755–59) in the English Channel now known as Smeaton's Tower. He needed a hydraulic mortar that would set and develop some strength in the twelve-hour period between successive high tides. He performed experiments with combinations of different limestones and additives including trass and pozzolanas[11] and did exhaustive market research on the available hydraulic limes, visiting their production sites, and noted that the "hydraulicity" of the lime was directly related to the clay content of the limestone used to make it. Smeaton was a civil engineer by profession, and took the idea no further.

In the South Atlantic seaboard of the United States, tabby relying on the oyster-shell middens of earlier Native American populations was used in house construction from the 1730s to the 1860s.[25]

In Britain particularly, good quality building stone became ever more expensive during a period of rapid growth, and it became a common practice to construct prestige buildings from the new industrial bricks, and to finish them with a stucco to imitate stone. Hydraulic limes were favored for this, but the need for a fast set time encouraged the development of new cements. Most famous was Parker's "Roman cement".[26] This was developed by James Parker in the 1780s, and finally patented in 1796. It was, in fact, nothing like material used by the Romans, but was a "natural cement" made by burning septaria – nodules that are found in certain clay deposits, and that contain both clay minerals and calcium carbonate. The burnt nodules were ground to a fine powder. This product, made into a mortar with sand, set in 5–15 minutes. The success of "Roman cement" led other manufacturers to develop rival products by burning artificial hydraulic lime cements of clay and chalk. Roman cement quickly became popular but was largely replaced by Portland cement in the 1850s.[11]

19th century

[edit]

Apparently unaware of Smeaton's work, the same principle was identified by Frenchman Louis Vicat in the first decade of the nineteenth century. Vicat went on to devise a method of combining chalk and clay into an intimate mixture, and, burning this, produced an "artificial cement" in 1817[27] considered the "principal forerunner"[11] of Portland cement and "...Edgar Dobbs of Southwark patented a cement of this kind in 1811."[11]

In Russia, Egor Cheliev created a new binder by mixing lime and clay. His results were published in 1822 in his book A Treatise on the Art to Prepare a Good Mortar published in St. Petersburg. A few years later in 1825, he published another book, which described various methods of making cement and concrete, and the benefits of cement in the construction of buildings and embankments.[28][29]

William Aspdin is considered the inventor of "modern" Portland cement.[30]

William Aspdin is considered the inventor of "modern" Portland cement.[30]

Portland cement, the most common type of cement in general use around the world as a basic ingredient of concrete, mortar, stucco, and non-speciality grout, was developed in England in the mid 19th century, and usually originates from limestone. James Frost produced what he called "British cement" in a similar manner around the same time, but did not obtain a patent until 1822.[31] In 1824, Joseph Aspdin patented a similar material, which he called Portland cement, because the render made from it was in color similar to the prestigious Portland stone quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset, England. However, Aspdins' cement was nothing like modern Portland cement but was a first step in its development, called a proto-Portland cement.[11] Joseph Aspdins' son William Aspdin had left his father's company and in his cement manufacturing apparently accidentally produced calcium silicates in the 1840s, a middle step in the development of Portland cement. William Aspdin's innovation was counterintuitive for manufacturers of "artificial cements", because they required more lime in the mix (a problem for his father), a much higher kiln temperature (and therefore more fuel), and the resulting clinker was very hard and rapidly wore down the millstones, which were the only available grinding technology of the time. Manufacturing costs were therefore considerably higher, but the product set reasonably slowly and developed strength quickly, thus opening up a market for use in concrete. The use of concrete in construction grew rapidly from 1850 onward, and was soon the dominant use for cements. Thus Portland cement began its predominant role. Isaac Charles Johnson further refined the production of meso-Portland cement (middle stage of development) and claimed he was the real father of Portland cement.[32]

Setting time and "early strength" are important characteristics of cements. Hydraulic limes, "natural" cements, and "artificial" cements all rely on their belite (2 CaO · SiO2, abbreviated as C2S) content for strength development. Belite develops strength slowly. Because they were burned at temperatures below 1,250 °C (2,280 °F), they contained no alite (3 CaO · SiO2, abbreviated as C3S), which is responsible for early strength in modern cements. The first cement to consistently contain alite was made by William Aspdin in the early 1840s: This was what we call today "modern" Portland cement. Because of the air of mystery with which William Aspdin surrounded his product, others (e.g., Vicat and Johnson) have claimed precedence in this invention, but recent analysis[33] of both his concrete and raw cement have shown that William Aspdin's product made at Northfleet, Kent was a true alite-based cement. However, Aspdin's methods were "rule-of-thumb": Vicat is responsible for establishing the chemical basis of these cements, and Johnson established the importance of sintering the mix in the kiln.

In the US the first large-scale use of cement was Rosendale cement, a natural cement mined from a massive deposit of dolomite discovered in the early 19th century near Rosendale, New York. Rosendale cement was extremely popular for the foundation of buildings (e.g., Statue of Liberty, Capitol Building, Brooklyn Bridge) and lining water pipes.[34] Sorel cement, or magnesia-based cement, was patented in 1867 by the Frenchman Stanislas Sorel.[35] It was stronger than Portland cement but its poor water resistance (leaching) and corrosive properties (pitting corrosion due to the presence of leachable chloride anions and the low pH (8.5–9.5) of its pore water) limited its use as reinforced concrete for building construction.[36]

The next development in the manufacture of Portland cement was the introduction of the rotary kiln. It produced a clinker mixture that was both stronger, because more alite (C3S) is formed at the higher temperature it achieved (1450 °C), and more homogeneous. Because raw material is constantly fed into a rotary kiln, it allowed a continuous manufacturing process to replace lower capacity batch production processes.[11]

20th century

[edit]

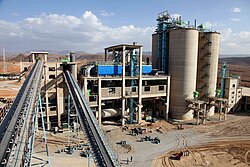

The National Cement Share Company of Ethiopia's new plant in Dire Dawa

The National Cement Share Company of Ethiopia's new plant in Dire Dawa

Calcium aluminate cements were patented in 1908 in France by Jules Bied for better resistance to sulfates.[37] Also in 1908, Thomas Edison experimented with pre-cast concrete in houses in Union, N.J.[38]

In the US, after World War One, the long curing time of at least a month for Rosendale cement made it unpopular for constructing highways and bridges, and many states and construction firms turned to Portland cement. Because of the switch to Portland cement, by the end of the 1920s only one of the 15 Rosendale cement companies had survived. But in the early 1930s, builders discovered that, while Portland cement set faster, it was not as durable, especially for highways—to the point that some states stopped building highways and roads with cement. Bertrain H. Wait, an engineer whose company had helped construct the New York City's Catskill Aqueduct, was impressed with the durability of Rosendale cement, and came up with a blend of both Rosendale and Portland cements that had the good attributes of both. It was highly durable and had a much faster setting time. Wait convinced the New York Commissioner of Highways to construct an experimental section of highway near New Paltz, New York, using one sack of Rosendale to six sacks of Portland cement. It was a success, and for decades the Rosendale-Portland cement blend was used in concrete highway and concrete bridge construction.[34]

Cementitious materials have been used as a nuclear waste immobilizing matrix for more than a half-century.[39] Technologies of waste cementation have been developed and deployed at industrial scale in many countries. Cementitious wasteforms require a careful selection and design process adapted to each specific type of waste to satisfy the strict waste acceptance criteria for long-term storage and disposal.[40]

Types

[edit]

Components of cement:

comparison of chemical and physical characteristics[a][41][42][43]

| Property |

Portland

cement |

Siliceous[b]

fly ash |

Calcareous[c]

fly ash |

Slag

cement |

Silica

fume |

| SiO2 |

21.9 |

52 |

35 |

35 |

85–97 |

| Al2O3 |

6.9 |

23 |

18 |

12 |

— |

| Fe2O3 |

3 |

11 |

6 |

1 |

— |

| CaO |

63 |

5 |

21 |

40 |

< 1 |

| MgO |

2.5 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| SO3 |

1.7 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| Specific surface (m2/kg)[d] |

370 |

420 |

420 |

400 |

15,000

– 30,000 |

| Specific gravity |

3.15 |

2.38 |

2.65 |

2.94 |

2.22 |

| General purpose |

Primary binder |

Cement replacement |

Cement replacement |

Cement replacement |

Property enhancer |

- ^ Values shown are approximate: those of a specific material may vary.

- ^ ASTM C618 Class F

- ^ ASTM C618 Class C

- ^ Specific surface measurements for silica fume by nitrogen adsorption (BET) method, others by air permeability method (Blaine).

|

Modern development of hydraulic cement began with the start of the Industrial Revolution (around 1800), driven by three main needs:

- Hydraulic cement render (stucco) for finishing brick buildings in wet climates

- Hydraulic mortars for masonry construction of harbor works, etc., in contact with sea water

- Development of strong concretes

Modern cements are often Portland cement or Portland cement blends, but other cement blends are used in some industrial settings.

Portland cement

[edit]

Main article: Portland cement

Portland cement, a form of hydraulic cement, is by far the most common type of cement in general use around the world. This cement is made by heating limestone (calcium carbonate) with other materials (such as clay) to 1,450 °C (2,640 °F) in a kiln, in a process known as calcination that liberates a molecule of carbon dioxide from the calcium carbonate to form calcium oxide, or quicklime, which then chemically combines with the other materials in the mix to form calcium silicates and other cementitious compounds. The resulting hard substance, called 'clinker', is then ground with a small amount of gypsum (

CaSO4·2H2O) into a powder to make ordinary Portland cement, the most commonly used type of cement (often referred to as OPC). Portland cement is a basic ingredient of concrete, mortar, and most non-specialty grout. The most common use for Portland cement is to make concrete. Portland cement may be grey or white.

Portland cement blend

[edit]

Portland cement blends are often available as inter-ground mixtures from cement producers, but similar formulations are often also mixed from the ground components at the concrete mixing plant.

Portland blast-furnace slag cement, or blast furnace cement (ASTM C595 and EN 197-1 nomenclature respectively), contains up to 95% ground granulated blast furnace slag, with the rest Portland clinker and a little gypsum. All compositions produce high ultimate strength, but as slag content is increased, early strength is reduced, while sulfate resistance increases and heat evolution diminishes. Used as an economic alternative to Portland sulfate-resisting and low-heat cements.

Portland-fly ash cement contains up to 40% fly ash under ASTM standards (ASTM C595), or 35% under EN standards (EN 197–1). The fly ash is pozzolanic, so that ultimate strength is maintained. Because fly ash addition allows a lower concrete water content, early strength can also be maintained. Where good quality cheap fly ash is available, this can be an economic alternative to ordinary Portland cement.[44]

Portland pozzolan cement includes fly ash cement, since fly ash is a pozzolan, but also includes cements made from other natural or artificial pozzolans. In countries where volcanic ashes are available (e.g., Italy, Chile, Mexico, the Philippines), these cements are often the most common form in use. The maximum replacement ratios are generally defined as for Portland-fly ash cement.

Portland silica fume cement. Addition of silica fume can yield exceptionally high strengths, and cements containing 5–20% silica fume are occasionally produced, with 10% being the maximum allowed addition under EN 197–1. However, silica fume is more usually added to Portland cement at the concrete mixer.[45]

Masonry cements are used for preparing bricklaying mortars and stuccos, and must not be used in concrete. They are usually complex proprietary formulations containing Portland clinker and a number of other ingredients that may include limestone, hydrated lime, air entrainers, retarders, waterproofers, and coloring agents. They are formulated to yield workable mortars that allow rapid and consistent masonry work. Subtle variations of masonry cement in North America are plastic cements and stucco cements. These are designed to produce a controlled bond with masonry blocks.

Expansive cements contain, in addition to Portland clinker, expansive clinkers (usually sulfoaluminate clinkers), and are designed to offset the effects of drying shrinkage normally encountered in hydraulic cements. This cement can make concrete for floor slabs (up to 60 m square) without contraction joints.

White blended cements may be made using white clinker (containing little or no iron) and white supplementary materials such as high-purity metakaolin. Colored cements serve decorative purposes. Some standards allow the addition of pigments to produce colored Portland cement. Other standards (e.g., ASTM) do not allow pigments in Portland cement, and colored cements are sold as blended hydraulic cements.

Very finely ground cements are cement mixed with sand or with slag or other pozzolan type minerals that are extremely finely ground together. Such cements can have the same physical characteristics as normal cement but with 50% less cement, particularly because there is more surface area for the chemical reaction. Even with intensive grinding they can use up to 50% less energy (and thus less carbon emissions) to fabricate than ordinary Portland cements.[46]

Other

[edit]

Pozzolan-lime cements are mixtures of ground pozzolan and lime. These are the cements the Romans used, and are present in surviving Roman structures like the Pantheon in Rome. They develop strength slowly, but their ultimate strength can be very high. The hydration products that produce strength are essentially the same as those in Portland cement.

Slag-lime cements—ground granulated blast-furnace slag—are not hydraulic on their own, but are "activated" by addition of alkalis, most economically using lime. They are similar to pozzolan lime cements in their properties. Only granulated slag (i.e., water-quenched, glassy slag) is effective as a cement component.

Supersulfated cements contain about 80% ground granulated blast furnace slag, 15% gypsum or anhydrite and a little Portland clinker or lime as an activator. They produce strength by formation of ettringite, with strength growth similar to a slow Portland cement. They exhibit good resistance to aggressive agents, including sulfate.

Calcium aluminate cements are hydraulic cements made primarily from limestone and bauxite. The active ingredients are monocalcium aluminate CaAl2O4 (CaO · Al2O3 or CA in cement chemist notation, CCN) and mayenite Ca12Al14O33 (12 CaO · 7 Al2O3, or C12A7 in CCN). Strength forms by hydration to calcium aluminate hydrates. They are well-adapted for use in refractory (high-temperature resistant) concretes, e.g., for furnace linings.

Calcium sulfoaluminate cements are made from clinkers that include ye'elimite (Ca4(AlO2)6SO4 or C4A3S in Cement chemist's notation) as a primary phase. They are used in expansive cements, in ultra-high early strength cements, and in "low-energy" cements. Hydration produces ettringite, and specialized physical properties (such as expansion or rapid reaction) are obtained by adjustment of the availability of calcium and sulfate ions. Their use as a low-energy alternative to Portland cement has been pioneered in China, where several million tonnes per year are produced.[47][48] Energy requirements are lower because of the lower kiln temperatures required for reaction, and the lower amount of limestone (which must be endothermically decarbonated) in the mix. In addition, the lower limestone content and lower fuel consumption leads to a CO

2 emission around half that associated with Portland clinker. However, SO2 emissions are usually significantly higher.

"Natural" cements corresponding to certain cements of the pre-Portland era, are produced by burning argillaceous limestones at moderate temperatures. The level of clay components in the limestone (around 30–35%) is such that large amounts of belite (the low-early strength, high-late strength mineral in Portland cement) are formed without the formation of excessive amounts of free lime. As with any natural material, such cements have highly variable properties.

Geopolymer cements are made from mixtures of water-soluble alkali metal silicates, and aluminosilicate mineral powders such as fly ash and metakaolin.

Polymer cements are made from organic chemicals that polymerise. Producers often use thermoset materials. While they are often significantly more expensive, they can give a water proof material that has useful tensile strength.

Sorel cement is a hard, durable cement made by combining magnesium oxide and a magnesium chloride solution

Fiber mesh cement or fiber reinforced concrete is cement that is made up of fibrous materials like synthetic fibers, glass fibers, natural fibers, and steel fibers. This type of mesh is distributed evenly throughout the wet concrete. The purpose of fiber mesh is to reduce water loss from the concrete as well as enhance its structural integrity.[49] When used in plasters, fiber mesh increases cohesiveness, tensile strength, impact resistance, and to reduce shrinkage; ultimately, the main purpose of these combined properties is to reduce cracking.[50]

Electric cement is proposed to be made by recycling cement from demolition wastes in an electric arc furnace as part of a steelmaking process. The recycled cement is intended to be used to replace part or all of the lime used in steelmaking, resulting in a slag-like material that is similar in mineralogy to Portland cement, eliminating most of the associated carbon emissions.[51]

Setting, hardening and curing

[edit]

Cement starts to set when mixed with water, which causes a series of hydration chemical reactions. The constituents slowly hydrate and the mineral hydrates solidify and harden. The interlocking of the hydrates gives cement its strength. Contrary to popular belief, hydraulic cement does not set by drying out — proper curing requires maintaining the appropriate moisture content necessary for the hydration reactions during the setting and the hardening processes. If hydraulic cements dry out during the curing phase, the resulting product can be insufficiently hydrated and significantly weakened. A minimum temperature of 5 °C is recommended, and no more than 30 °C.[52] The concrete at young age must be protected against water evaporation due to direct insolation, elevated temperature, low relative humidity and wind.

The interfacial transition zone (ITZ) is a region of the cement paste around the aggregate particles in concrete. In the zone, a gradual transition in the microstructural features occurs.[53] This zone can be up to 35 micrometer wide.[54]: 351  Other studies have shown that the width can be up to 50 micrometer. The average content of unreacted clinker phase decreases and porosity decreases towards the aggregate surface. Similarly, the content of ettringite increases in ITZ. [54]: 352

Safety issues

[edit]

Bags of cement routinely have health and safety warnings printed on them because not only is cement highly alkaline, but the setting process is exothermic. As a result, wet cement is strongly caustic (pH = 13.5) and can easily cause severe skin burns if not promptly washed off with water. Similarly, dry cement powder in contact with mucous membranes can cause severe eye or respiratory irritation. Some trace elements, such as chromium, from impurities naturally present in the raw materials used to produce cement may cause allergic dermatitis.[55] Reducing agents such as ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) are often added to cement to convert the carcinogenic hexavalent chromate (CrO42−) into trivalent chromium (Cr3+), a less toxic chemical species. Cement users need also to wear appropriate gloves and protective clothing.[56]

Cement industry in the world

[edit]

Global cement production in 2022

Global cement production in 2022

Global cement capacity in 2022

Global cement capacity in 2022

See also: List of countries by cement production and Cement industry in the United States

In 2010, the world production of hydraulic cement was 3,300 megatonnes (3,600×10^6 short tons). The top three producers were China with 1,800, India with 220, and the United States with 63.5 million tonnes for a total of over half the world total by the world's three most populated states.[57]

For the world capacity to produce cement in 2010, the situation was similar with the top three states (China, India, and the US) accounting for just under half the world total capacity.[58]

Over 2011 and 2012, global consumption continued to climb, rising to 3585 Mt in 2011 and 3736 Mt in 2012, while annual growth rates eased to 8.3% and 4.2%, respectively.

China, representing an increasing share of world cement consumption, remains the main engine of global growth. By 2012, Chinese demand was recorded at 2160 Mt, representing 58% of world consumption. Annual growth rates, which reached 16% in 2010, appear to have softened, slowing to 5–6% over 2011 and 2012, as China's economy targets a more sustainable growth rate.

Outside of China, worldwide consumption climbed by 4.4% to 1462 Mt in 2010, 5% to 1535 Mt in 2011, and finally 2.7% to 1576 Mt in 2012.

Iran is now the 3rd largest cement producer in the world and has increased its output by over 10% from 2008 to 2011.[59] Because of climbing energy costs in Pakistan and other major cement-producing countries, Iran is in a unique position as a trading partner, utilizing its own surplus petroleum to power clinker plants. Now a top producer in the Middle-East, Iran is further increasing its dominant position in local markets and abroad.[60]

The performance in North America and Europe over the 2010–12 period contrasted strikingly with that of China, as the global financial crisis evolved into a sovereign debt crisis for many economies in this region[clarification needed] and recession. Cement consumption levels for this region fell by 1.9% in 2010 to 445 Mt, recovered by 4.9% in 2011, then dipped again by 1.1% in 2012.

The performance in the rest of the world, which includes many emerging economies in Asia, Africa and Latin America and representing some 1020 Mt cement demand in 2010, was positive and more than offset the declines in North America and Europe. Annual consumption growth was recorded at 7.4% in 2010, moderating to 5.1% and 4.3% in 2011 and 2012, respectively.

As at year-end 2012, the global cement industry consisted of 5673 cement production facilities, including both integrated and grinding, of which 3900 were located in China and 1773 in the rest of the world.

Total cement capacity worldwide was recorded at 5245 Mt in 2012, with 2950 Mt located in China and 2295 Mt in the rest of the world.[6]

China

[edit]

Main article: Cement industry in China

"For the past 18 years, China consistently has produced more cement than any other country in the world. [...] (However,) China's cement export peaked in 1994 with 11 million tonnes shipped out and has been in steady decline ever since. Only 5.18 million tonnes were exported out of China in 2002. Offered at $34 a ton, Chinese cement is pricing itself out of the market as Thailand is asking as little as $20 for the same quality."[61]

In 2006, it was estimated that China manufactured 1.235 billion tonnes of cement, which was 44% of the world total cement production.[62] "Demand for cement in China is expected to advance 5.4% annually and exceed 1 billion tonnes in 2008, driven by slowing but healthy growth in construction expenditures. Cement consumed in China will amount to 44% of global demand, and China will remain the world's largest national consumer of cement by a large margin."[63]

In 2010, 3.3 billion tonnes of cement was consumed globally. Of this, China accounted for 1.8 billion tonnes.[64]

Environmental impacts

[edit]

Further information: Environmental impact of concrete

Cement manufacture causes environmental impacts at all stages of the process. These include emissions of airborne pollution in the form of dust, gases, noise and vibration when operating machinery and during blasting in quarries, and damage to countryside from quarrying. Equipment to reduce dust emissions during quarrying and manufacture of cement is widely used, and equipment to trap and separate exhaust gases are coming into increased use. Environmental protection also includes the re-integration of quarries into the countryside after they have been closed down by returning them to nature or re-cultivating them.

CO

2 emissions

[edit]

Global carbon emission by type to 2018

Global carbon emission by type to 2018

Carbon concentration in cement spans from ≈5% in cement structures to ≈8% in the case of roads in cement.[65] Cement manufacturing releases CO2 in the atmosphere both directly when calcium carbonate is heated, producing lime and carbon dioxide,[66][67] and also indirectly through the use of energy if its production involves the emission of CO

2. The cement industry produces about 10% of global human-made CO

2 emissions, of which 60% is from the chemical process, and 40% from burning fuel.[68] A Chatham House study from 2018 estimates that the 4 billion tonnes of cement produced annually account for 8% of worldwide CO

2 emissions.[5]

Nearly 900 kg of CO

2 are emitted for every 1000 kg of Portland cement produced. In the European Union, the specific energy consumption for the production of cement clinker has been reduced by approximately 30% since the 1970s. This reduction in primary energy requirements is equivalent to approximately 11 million tonnes of coal per year with corresponding benefits in reduction of CO

2 emissions. This accounts for approximately 5% of anthropogenic CO

2.[69]

The majority of carbon dioxide emissions in the manufacture of Portland cement (approximately 60%) are produced from the chemical decomposition of limestone to lime, an ingredient in Portland cement clinker. These emissions may be reduced by lowering the clinker content of cement. They can also be reduced by alternative fabrication methods such as the intergrinding cement with sand or with slag or other pozzolan type minerals to a very fine powder.[70]

To reduce the transport of heavier raw materials and to minimize the associated costs, it is more economical to build cement plants closer to the limestone quarries rather than to the consumer centers.[71]

As of 2019[update] carbon capture and storage is about to be trialed, but its financial viability is uncertain.[72]

CO

2 absorption

[edit]

Hydrated products of Portland cement, such as concrete and mortars, slowly reabsorb atmospheric CO2 gas, which has been released during calcination in a kiln. This natural process, reversed to calcination, is called carbonation.[73] As it depends on CO2 diffusion into the bulk of concrete, its rate depends on many parameters, such as environmental conditions and surface area exposed to the atmosphere.[74][75] Carbonation is particularly significant at the latter stages of the concrete life - after demolition and crushing of the debris. It was estimated that during the whole life-cycle of cement products, it can be reabsorbed nearly 30% of atmospheric CO2 generated by cement production.[75]

Carbonation process is considered as a mechanism of concrete degradation. It reduces pH of concrete that promotes reinforcement steel corrosion.[73] However, as the product of Ca(OH)2 carbonation, CaCO3, occupies a greater volume, porosity of concrete reduces. This increases strength and hardness of concrete.[76]

There are proposals to reduce carbon footprint of hydraulic cement by adopting non-hydraulic cement, lime mortar, for certain applications. It reabsorbs some of the CO

2 during hardening, and has a lower energy requirement in production than Portland cement.[77]

A few other attempts to increase absorption of carbon dioxide include cements based on magnesium (Sorel cement).[78][79][80]

[edit]

In some circumstances, mainly depending on the origin and the composition of the raw materials used, the high-temperature calcination process of limestone and clay minerals can release in the atmosphere gases and dust rich in volatile heavy metals, e.g. thallium,[81] cadmium and mercury are the most toxic. Heavy metals (Tl, Cd, Hg, ...) and also selenium are often found as trace elements in common metal sulfides (pyrite (FeS2), zinc blende (ZnS), galena (PbS), ...) present as secondary minerals in most of the raw materials. Environmental regulations exist in many countries to limit these emissions. As of 2011 in the United States, cement kilns are "legally allowed to pump more toxins into the air than are hazardous-waste incinerators."[82]

[edit]

The presence of heavy metals in the clinker arises both from the natural raw materials and from the use of recycled by-products or alternative fuels. The high pH prevailing in the cement porewater (12.5 < pH < 13.5) limits the mobility of many heavy metals by decreasing their solubility and increasing their sorption onto the cement mineral phases. Nickel, zinc and lead are commonly found in cement in non-negligible concentrations. Chromium may also directly arise as natural impurity from the raw materials or as secondary contamination from the abrasion of hard chromium steel alloys used in the ball mills when the clinker is ground. As chromate (CrO42−) is toxic and may cause severe skin allergies at trace concentration, it is sometimes reduced into trivalent Cr(III) by addition of ferrous sulfate (FeSO4).

Use of alternative fuels and by-products materials

[edit]

A cement plant consumes 3 to 6 GJ of fuel per tonne of clinker produced, depending on the raw materials and the process used. Most cement kilns today use coal and petroleum coke as primary fuels, and to a lesser extent natural gas and fuel oil. Selected waste and by-products with recoverable calorific value can be used as fuels in a cement kiln (referred to as co-processing), replacing a portion of conventional fossil fuels, like coal, if they meet strict specifications. Selected waste and by-products containing useful minerals such as calcium, silica, alumina, and iron can be used as raw materials in the kiln, replacing raw materials such as clay, shale, and limestone. Because some materials have both useful mineral content and recoverable calorific value, the distinction between alternative fuels and raw materials is not always clear. For example, sewage sludge has a low but significant calorific value, and burns to give ash containing minerals useful in the clinker matrix.[83] Scrap automobile and truck tires are useful in cement manufacturing as they have high calorific value and the iron embedded in tires is useful as a feed stock.[84]: p. 27

Clinker is manufactured by heating raw materials inside the main burner of a kiln to a temperature of 1,450 °C. The flame reaches temperatures of 1,800 °C. The material remains at 1,200 °C for 12–15 seconds at 1,800 °C or sometimes for 5–8 seconds (also referred to as residence time). These characteristics of a clinker kiln offer numerous benefits and they ensure a complete destruction of organic compounds, a total neutralization of acid gases, sulphur oxides and hydrogen chloride. Furthermore, heavy metal traces are embedded in the clinker structure and no by-products, such as ash or residues, are produced.[85]

The EU cement industry already uses more than 40% fuels derived from waste and biomass in supplying the thermal energy to the grey clinker making process. Although the choice for this so-called alternative fuels (AF) is typically cost driven, other factors are becoming more important. Use of alternative fuels provides benefits for both society and the company: CO

2-emissions are lower than with fossil fuels, waste can be co-processed in an efficient and sustainable manner and the demand for certain virgin materials can be reduced. Yet there are large differences in the share of alternative fuels used between the European Union (EU) member states. The societal benefits could be improved if more member states increase their alternative fuels share. The Ecofys study[86] assessed the barriers and opportunities for further uptake of alternative fuels in 14 EU member states. The Ecofys study found that local factors constrain the market potential to a much larger extent than the technical and economic feasibility of the cement industry itself.

[edit]

Growing environmental concerns and the increasing cost of fossil fuels have resulted, in many countries, in a sharp reduction of the resources needed to produce cement, as well as effluents (dust and exhaust gases).[87] Reduced-footprint cement is a cementitious material that meets or exceeds the functional performance capabilities of Portland cement. Various techniques are under development. One is geopolymer cement, which incorporates recycled materials, thereby reducing consumption of raw materials, water, and energy. Another approach is to reduce or eliminate the production and release of damaging pollutants and greenhouse gasses, particularly CO

2.[88] Recycling old cement in electric arc furnaces is another approach.[89] Also, a team at the University of Edinburgh has developed the 'DUPE' process based on the microbial activity of Sporosarcina pasteurii, a bacterium precipitating calcium carbonate, which, when mixed with sand and urine, can produce mortar blocks with a compressive strength 70% of that of concrete.[90] An overview of climate-friendly methods for cement production can be found here.[91]

See also

[edit]

- Asphalt concrete

- Calcium aluminate cements

- Cement chemist notation

- Cement render

- Cenocell

- Energetically modified cement (EMC)

- Fly ash

- Geopolymer cement

- Portland cement

- Rosendale cement

- Sulfate attack in concrete and mortar

- Sulfur concrete

- Tiocem

- List of countries by cement production

References

[edit]

- ^

"Draeger: Guide for selection and use of filtering devices" (PDF). Draeger. 22 May 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b Rodgers, Lucy (17 December 2018). "The massive CO

2 emitter you may not know about". BBC News. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Cement Analyst, Milan A (2015), Lancaster, Lynne C. (ed.), "Opus Caementicium", Innovative Vaulting in the Architecture of the Roman Empire: 1st to 4th Centuries CE, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–38, ISBN 978-1-107-05935-1, retrieved 7 March 2025

- ^ a b "Cement" (PDF). United States Geological Survey (USGS). Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "Making Concrete Change: Innovation in Low-carbon Cement and Concrete". Chatham House. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ a b Hargreaves, David (March 2013). "The Global Cement Report 10th Edition" (PDF). International Cement Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2013.

- ^ Cao, Zhi; Myers, Rupert J.; Lupton, Richard C.; Duan, Huabo; Sacchi, Romain; Zhou, Nan; Reed Miller, T.; Cullen, Jonathan M.; Ge, Quansheng; Liu, Gang (29 July 2020). "The sponge effect and carbon emission mitigation potentials of the global cement cycle". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3777. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3777C. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17583-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7392754. PMID 32728073.

- ^ "Cement's basic molecular structure finally decoded (MIT, 2009)". Archived from the original on 21 February 2013.

- ^ "EPA Overview of Greenhouse Gases". 23 December 2015.

- ^ "The History of Concrete". Dept. of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Blezard, Robert G. (12 November 2003). "The History of Calcareous Cements". In Hewlett, Peter (ed.). Lea's Chemistry of Cement and Concrete. Elsevier. pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-0-08-053541-8.

- ^ Brabant, Malcolm (12 April 2011). Macedonians created cement three centuries before the Romans Archived 9 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News.

- ^ "Heracles to Alexander The Great: Treasures From The Royal Capital of Macedon, A Hellenic Kingdom in the Age of Democracy". Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ^ Hill, Donald (19 November 2013). A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-317-76157-0.

- ^ "History of cement". www.understanding-cement.com. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Trendacosta, Katharine (18 December 2014). "How the Ancient Romans Made Better Concrete Than We Do Now". Gizmodo.

- ^ "How Natural Pozzolans Improve Concrete". Natural Pozzolan Association. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Ridi, Francesca (April 2010). "Hydration of Cement: still a lot to be understood" (PDF). La Chimica & l'Industria (3): 110–117. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ "Pure natural pozzolan cement" (PDF). Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

cite web: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). chamorro.com

- ^ Russo, Ralph (2006) "Aqueduct Architecture: Moving Water to the Masses in Ancient Rome" Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, in Math in the Beauty and Realization of Architecture, Vol. IV, Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1978–2012, Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute.

- ^ a b Cowan, Henry J. (1975). "An Historical Note on Concrete". Architectural Science Review. 18: 10–13. doi:10.1080/00038628.1975.9696342.

- ^ Cabrera, J. G.; Rivera-Villarreal, R.; Sri Ravindrarajah, R. (1997). "Properties and Durability of a Pre-Columbian Lightweight Concrete". SP-170: Fourth CANMET/ACI International Conference on Durability of Concrete. Vol. 170. pp. 1215–1230. doi:10.14359/6874. ISBN 9780870316692. S2CID 138768044.

- ^ a b Sismondo, Sergio (20 November 2009). An Introduction to Science and Technology Studies. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4443-1512-7.

- ^ Mukerji, Chandra (2009). Impossible Engineering: Technology and Territoriality on the Canal Du Midi. Princeton University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-691-14032-2.

- ^ a b <Taves, Loren Sickels (27 October 2015). "Tabby Houses of the South Atlantic Seaboard". Old-House Journal. Active Interest Media, Inc.: 5.

- ^ Francis, A.J. (1977) The Cement Industry 1796–1914: A History, David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7386-2, Ch. 2.

- ^ "Who Discovered Cement". 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013.

- ^ Znachko-Iavorskii; I. L. (1969). Egor Gerasimovich Chelidze, izobretatelʹ tsementa. Sabchota Sakartvelo. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- ^ "Lafarge History of Cement". Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- ^ Courland, Robert (2011). Concrete planet : the strange and fascinating story of the world's most common man-made material. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. p. 190. ISBN 978-1616144814.

- ^ Francis, A.J. (1977) The Cement Industry 1796–1914: A History, David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7386-2, Ch. 5.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas F. and Kemp, Emory Leland (1994). Cement mills along the Potomac River. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781885907004

- ^ Hewlett, Peter (2003). Lea's Chemistry of Cement and Concrete. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. Ch. 1. ISBN 978-0-08-053541-8. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Natural Cement Comes Back". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. October 1941. p. 118.

- ^ Stanislas Sorel (1867). "Sur un nouveau ciment magnésien". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences, volume 65, pages 102–104.

- ^ Walling, Sam A.; Provis, John L. (2016). "Magnesia-based cements: A journey of 150 years, and cements for the future?". Chemical Reviews. 116 (7): 4170–4204. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00463. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 27002788.

- ^ McArthur, H.; Spalding, D. (1 January 2004). Engineering Materials Science: Properties, Uses, Degradation, Remediation. Elsevier. ISBN 9781782420491.

- ^ "How Cement Mixers Work". HowStuffWorks. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Glasser F. (2011). Application of inorganic cements to the conditioning and immobilisation of radioactive wastes. In: Ojovan M.I. (2011). Handbook of advanced radioactive waste conditioning technologies. Woodhead, Cambridge, 512 pp.

- ^ Abdel Rahman R.O., Rahimov R.Z., Rahimova N.R., Ojovan M.I. (2015). Cementitious materials for nuclear waste immobilization. Wiley, Chichester 232 pp.

- ^ Holland, Terence C. (2005). "Silica Fume User's Manual" (PDF). Silica Fume Association and United States Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Technical Report FHWA-IF-05-016. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Kosmatka, S.; Kerkhoff, B.; Panerese, W. (2002). Design and Control of Concrete Mixtures (14 ed.). Portland Cement Association, Skokie, Illinois.

- ^ Gamble, William. "Cement, Mortar, and Concrete". In Baumeister; Avallone; Baumeister (eds.). Mark's Handbook for Mechanical Engineers (Eighth ed.). McGraw Hill. Section 6, page 177.

- ^ U.S. Federal Highway Administration. "Fly Ash". Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2007.

- ^ U.S. Federal Highway Administration. "Silica Fume". Archived from the original on 22 January 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2007.

- ^ Justnes, Harald; Elfgren, Lennart; Ronin, Vladimir (2005). "Mechanism for performance of energetically modified cement versus corresponding blended cement" (PDF). Cement and Concrete Research. 35 (2): 315–323. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.05.022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2011.

- ^ Bye, G.C. (1999). Portland Cement. 2nd Ed., Thomas Telford. pp. 206–208. ISBN 0-7277-2766-4

- ^ Zhang, Liang; Su, Muzhen; Wang, Yanmou (1999). "Development of the use of sulfo- and ferroaluminate cements in China". Advances in Cement Research. 11: 15–21. doi:10.1680/adcr.1999.11.1.15.

- ^ Munsell, Faith (31 December 2019). "Concrete mesh: When to use fiber mesh or wire mesh | Port Aggregates". Port Aggregates. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Plaster / Stucco Manual" (PDF). Cement.org. 2003. p. 13. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Barnard, Michael (30 May 2024). "Many Green Cement Roads Lead Through Electric Arc Steel Furnaces". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Using cement based products during winter months". sovchem.co.uk. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018.

- ^ a b Scrivener, K.L., Crumbie, A.K., and Laugesen P. (2004). "The Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) between cement paste and aggregate in concrete." Interface Science, 12 (4), 411–421. doi: 10.1023/B:INTS.0000042339.92990.4c.

- ^ a b c H. F. W. Taylor, Cement chemistry, 2nd ed. London: T. Telford, 1997.

- ^ "Construction Information Sheet No 26 (revision2)" (PDF). hse.gov.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ "CIS26 – cement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ United States Geological Survey. "USGS Mineral Program Cement Report. (Jan 2011)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2011.

- ^ Edwards, P; McCaffrey, R. Global Cement Directory 2010. PRo Publications Archived 3 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Epsom, UK, 2010.

- ^ "Pakistan loses Afghan cement market share to Iran". International Cement Revie. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ ICR Newsroom. Pakistan loses Afghan cement market share to Iran Archived 22 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ Yan, Li Yong (7 January 2004) China's way forward paved in cement, Asia Times

- ^ "China now no. 1 in CO emissions; USA in second position: more info". NEAA. 19 June 2007. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007.

- ^ "China's cement demand to top 1 billion tonnes in 2008". CementAmericas. November 2004. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009.

- ^ "Uses of Coal and Cement". World Coal Association. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011.

- ^ Scalenghe, R.; Malucelli, F.; Ungaro, F.; Perazzone, L.; Filippi, N.; Edwards, A.C. (2011). "Influence of 150 years of land use on anthropogenic and natural carbon stocks in Emilia-Romagna Region (Italy)". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (12): 5112–5117. Bibcode:2011EnST...45.5112S. doi:10.1021/es1039437. PMID 21609007.

- ^ "EIA – Emissions of Greenhouse Gases in the U.S. 2006-Carbon Dioxide Emissions". US Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011.

- ^ Matar, W.; Elshurafa, A. M. (2017). "Striking a balance between profit and carbon dioxide emissions in the Saudi cement industry". International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control. 61: 111–123. Bibcode:2017IJGGC..61..111M. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2017.03.031.

- ^ "Trends in global CO

2 emissions: 2014 Report" (PDF). PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency & European Commission Joint Research Centre. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2016.

- ^ Mahasenan, Natesan; Smith, Steve; Humphreysm Kenneth; Kaya, Y. (2003). "The Cement Industry and Global Climate Change: Current and Potential Future Cement Industry CO

2 Emissions". Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies – 6th International Conference. Oxford: Pergamon. pp. 995–1000. ISBN 978-0-08-044276-1.

- ^ "Blended Cement". Science Direct. 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Chandak, Shobhit. "Report on cement industry in India". scribd. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "World's first zero-emission cement plant takes shape in Norway". Euractiv.com Ltd. 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b Pade, Claus; Guimaraes, Maria (1 September 2007). "The CO2 uptake of concrete in a 100 year perspective". Cement and Concrete Research. 37 (9): 1348–1356. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.06.009. ISSN 0008-8846.

- ^ Xi, Fengming; Davis, Steven J.; Ciais, Philippe; Crawford-Brown, Douglas; Guan, Dabo; Pade, Claus; Shi, Tiemao; Syddall, Mark; Lv, Jie; Ji, Lanzhu; Bing, Longfei; Wang, Jiaoyue; Wei, Wei; Yang, Keun-Hyeok; Lagerblad, Björn (December 2016). "Substantial global carbon uptake by cement carbonation". Nature Geoscience. 9 (12): 880–883. Bibcode:2016NatGe...9..880X. doi:10.1038/ngeo2840. ISSN 1752-0908.

- ^ a b Cao, Zhi; Myers, Rupert J.; Lupton, Richard C.; Duan, Huabo; Sacchi, Romain; Zhou, Nan; Reed Miller, T.; Cullen, Jonathan M.; Ge, Quansheng; Liu, Gang (29 July 2020). "The sponge effect and carbon emission mitigation potentials of the global cement cycle". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3777. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3777C. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17583-w. hdl:10044/1/81385. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7392754. PMID 32728073.

- ^ Kim, Jin-Keun; Kim, Chin-Yong; Yi, Seong-Tae; Lee, Yun (1 February 2009). "Effect of carbonation on the rebound number and compressive strength of concrete". Cement and Concrete Composites. 31 (2): 139–144. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2008.10.001. ISSN 0958-9465.

- ^ Kent, Douglas (22 October 2007). "Response: Lime is a much greener option than cement, says Douglas Kent". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Novacem's 'carbon negative cement'". The American Ceramic Society. 9 March 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "Novacem". imperialinnovations.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009.

- ^ Jha, Alok (31 December 2008). "Revealed: The cement that eats carbon dioxide". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Factsheet on: Thallium" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- ^ Berkes, Howard (10 November 2011). "EPA Regulations Give Kilns Permission To Pollute : NPR". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Guidelines for the selection and use of fuels and raw materials in the cement manufacturing process" (PDF). World Business Council for Sustainable Development. 1 June 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Increasing the use of alternative fuels at cement plants: International best practice" (PDF). International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group. 2017.

- ^ "Cement, concrete & the circular economy" (PDF). cembureau.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2018.

- ^ de Beer, Jeroen et al. (2017) Status and prospects of co-processing of waste in EU cement plants Archived 30 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine. ECOFYS study.

- ^ "Alternative fuels in cement manufacture – CEMBUREAU brochure, 1997" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013.

- ^ "Engineers develop cement with 97 percent smaller carbon dioxide and energy footprint – DrexelNow". DrexelNow. 20 February 2012. Archived from the original on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "How to make low-carbon concrete from old cement". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Monks, Kieron (22 May 2014). "Would you live in a house made of sand and bacteria? It's a surprisingly good idea". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Top-Innovationen 2020: Zement lässt sich auch klimafreundlich produzieren". www.spektrum.de (in German). Retrieved 28 December 2020.

Further reading

[edit]

- Taylor, Harry F. W. (1997). Cement Chemistry. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-2592-9.

- Peter Hewlett; Martin Liska (2019). Lea's Chemistry of Cement and Concrete. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-100795-2.

- Aitcin, Pierre-Claude (2000). "Cements of yesterday and today: Concrete of tomorrow". Cement and Concrete Research. 30 (9): 1349–1359. doi:10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00365-3.

- van Oss, Hendrik G.; Padovani, Amy C. (2002). "Cement manufacture and the environment, Part I: Chemistry and Technology". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 6 (1): 89–105. Bibcode:2002JInEc...6...89O. doi:10.1162/108819802320971650. S2CID 96660377.

- van Oss, Hendrik G.; Padovani, Amy C. (2003). "Cement manufacture and the environment, Part II: Environmental challenges and opportunities" (PDF). Journal of Industrial Ecology. 7 (1): 93–126. Bibcode:2003JInEc...7...93O. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.469.2404. doi:10.1162/108819803766729212. S2CID 44083686. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Deolalkar, S. P. (2016). Designing green cement plants. Amsterdam: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 9780128034354. OCLC 919920182.

- Friedrich W. Locher: Cement : Principles of production and use, Düsseldorf, Germany: Verlag Bau + Technik GmbH, 2006, ISBN 3-7640-0420-7

- Javed I. Bhatty, F. MacGregor Miller, Steven H. Kosmatka; editors: Innovations in Portland Cement Manufacturing, SP400, Portland Cement Association, Skokie, Illinois, U.S., 2004, ISBN 0-89312-234-3

- "Why cement emissions matter for climate change" Archived 21 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine Carbon Brief 2018

- Neville, A.M. (1996). Properties of concrete. Fourth and final edition standards. Pearson, Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-582-23070-5. OCLC 33837400.

- Taylor, H.F.W. (1990). Cement chemistry. Academic Press. p. 475. ISBN 978-0-12-683900-5.

- Ulm, Franz-Josef; Roland J.-M. Pellenq; Akihiro Kushima; Rouzbeh Shahsavari; Krystyn J. Van Vliet; Markus J. Buehler; Sidney Yip (2009). "A realistic molecular model of cement hydrates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16102–16107. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616102P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902180106. PMC 2739865. PMID 19805265.

External links

[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cement.

- "Cement" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

Technology and related concepts

| |

|

|

|

|

Perspectives

|

|

| Criticism |

- Appropriate technology

- Luddite

- Precautionary principle

|

| Ecotechnology |

- Environmental technology

- Sustainable design

|

| Policy & politics |

- Government by algorithm

- Intellectual property

- Persuasive technology

- Science policy

- Strategy of Technology

- Technology assessment

- Technorealism

|

| Progressivism |

- Futures studies

- Technological utopianism

- Technocracy movement

- Technological singularity

- Transhumanism

|

| Studies |

- Diffusion of innovations

- History

- Timeline of historic inventions

- Philosophy

- Social construction of technology

- Technological determinism

- Technology acceptance model

|

|

|

|

|

Related concepts

|

|

| Applied science |

- Agronomy

- Architecture

- Construction

- Engineering

- Forensics

- Forestry

- Logistics

- Medicine

- Mining

- Navigation

- Surveying

|

| Innovation |

- Design

- High tech

- Invention

- Mature technology

- Research and development

- Technological convergence

- Technology lifecycle

|

|

|

|

|

Concrete

| |

| History |

- Ancient Roman architecture

- Roman architectural revolution

- Roman concrete

- Roman engineering

- Roman technology

|

| Composition |

- Cement

- Calcium aluminate

- Energetically modified

- Portland

- Rosendale

- Water

- Water–cement ratio

- Aggregate

- Reinforcement

- Fly ash

- Ground granulated blast-furnace slag

- Silica fume

- Metakaolin

|

| Production |

- Plant

- Concrete mixer

- Volumetric mixer

- Reversing drum mixer

- Slump test

- Flow table test

- Curing

- Concrete cover

- Cover meter

- Rebar

|

| Construction |

- Precast

- Cast-in-place

- Formwork

- Climbing formwork

- Slip forming

- Screed

- Power screed

- Finisher

- Grinder

- Power trowel

- Pump

- Float

- Sealer

- Tremie

|

| Science |

- Properties

- Durability

- Degradation

- Environmental impact

- Recycling

- Segregation

- Alkali–silica reaction

|

| Types |

- AstroCrete

- Fiber-reinforced

- Filigree

- Foam

- Lunarcrete

- Mass

- Nanoconcrete

- Pervious

- Polished

- Polymer

- Prestressed

- Ready-mix

- Reinforced

- Roller-compacting

- Self-consolidating

- Self-leveling

- Sulfur

- Tabby

- Translucent

- Waste light

- Aerated

|

| Applications |

- Slab

- waffle

- hollow-core

- voided biaxial

- slab on grade

- Concrete block

- Step barrier

- Roads

- Columns

- Structures

|

| Organizations |

- American Concrete Institute

- Concrete Society

- Institution of Structural Engineers

- Indian Concrete Institute

- Nanocem

- Portland Cement Association

- International Federation for Structural Concrete

|

| Standards |

- Eurocode 2

- EN 197-1

- EN 206-1

- EN 10080

|

| See also |

|

Category:Concrete Category:Concrete

|

Major industries

| |

|

|

|

|

Industrial sector

|

|

| Manufacturing |

|

| Utilities |

- Power

- Electric

- Gas distribution

- Renewable

- Water

- Waste management

- Collection

- Dumping

- Hazardous

- Recycling

- Remediation

- Telecom networks

- Cable TV

- Internet

- Mobile

- Satellite

- Telephone

|

| Construction |

- Buildings

- Commercial

- Industrial

- Residential

- Civil engineering

- Bridges

- Railways

- Roads

- Tunnels

- Canals

- Dams

- Dredging

- Harbors

- Specialty trades

- Cabinetry

- Demolition

- Electrical wiring

- Elevators

- HVAC

- Painting and decorating

- Plumbing

- Site preparation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related

|

|

Classification

standards |

- Production-based

- ANZSIC

- ISIC

- NACE

- NAICS

- SIC

- UKSIC

- Market-based

- Other

|

Inputs

& outputs |

- Externalities

- Community

- Crime

- Culture

- Pollution

- Well-being

- Funding

- Goods

- Commodities

- Final

- Intermediate

- Raw material

- Innovation

- Primary inputs

- Labor

- Natural resources

- Physical capital

- Services

- Technology

|

| Organization |

- Centralization

- Cartel

- Conglomerate

- Horizontal integration

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Monopoly

- Monopsony

- Vertical integration

- Decentralization

- Enforced breakup

- Freelancing

- Homesteading

- Outsourcing

- Putting-out system

- Spinning-off

- Temporary work

- Ownership

- Cooperative

- Joint-stock company

- Nationalization

- Nonprofit organization

- Partnership

- Privatization

- Sole proprietorship

- State-owned enterprise

|

|

|

|

|

Authority control databases  |

| International |

|

| National |

- Germany

- United States

- France

- BnF data

- Japan

- Spain

- Latvia

- Israel

|

| Other |

- IdRef

- Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

|