Data Stories

Punitive Government Policies Jeopardise Kenya’s Food Security

The government is criminalising Kenyan farmers and leaving the country’s food security at the mercy of multinational corporations.

By 2021 your typical Kenyan smallholder farmer was producing 75 per cent of the foods consumed in the country. Yet the draconian laws imposed on the agriculture sector by the government have been facilitating their exploitation by private sector actors including multinational corporations. This is in total contradiction with President Uhuru Kenyatta’s move to include food security in his Big Four Agenda and begs the question of how the country can achieve food security when farmers are discouraged from producing food by these punitive laws.

Recently, there was an uproar on social media regarding the Livestock Bill 2021. The point of contention in the yet to be gazetted Bill is a clause that bars Kenyan farmers from keeping bees for commercial purposes unless they are registered under the Apiary Act. The government, through the Permanent Secretary for Livestock Mr Harry Kimutai, tried to justify this by saying that the aim of registering beekeepers is to commercialise beekeeping instead of it being a traditional practice.

Local pastoralist, agrarian and forest-dwelling communities have practiced beekeeping since time immemorial and it has been part of the subsistence economy of smallholder farmers who pass on this rich knowledge and expertise from generation to generation.

Bee-reaucracy

In its current form, the Livestock Bill 2021 will drive smallholder beekeepers out of honey production and pave the way for multinational corporations under the guise of regulating the sector. It is no different from the Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy 2019-2029 that seeks to move farmers out of farming into “more productive jobs”, opening the door for their exploitation and impoverishment by agro-capitalists.

In a recent media interview, Mr Kimutai said that Kenyan honey is contaminated with pesticide residues. But if the government is indeed concerned about improving honey production, it should start by banning the use of toxic pesticides that are detrimental to bees and contaminate the quality of honey. Pesticides such as Deltamethrin have been found to be toxic to bees yet they are still used in Kenya.

Local pastoralist, agrarian and forest-dwelling communities have practiced beekeeping since time immemorial.

Section 93 subsection(1) of the Bill bars the importation, manufacturing, compounding, mixing or selling of any animal foodstuff other than a product that the authority may by order declare to be an approved animal product. This offence attracts a fine of KSh500,000 or imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months, or both.

Smallholder livestock farmers in Kenya have been growing “napier grass” to feed their cows and for sale to other farmers. Do these new regulations mean that they shall be committing an offence by growing their own feed and selling it within their localities?

Another punitive regulation is the Crops (Irish Potato) Regulations 2019, that requires transporters, traders and dealers to be registered with their counties, failure to which they face up to KSh5 million in fines, three years imprisonment, or both. This regulation also punishes an unregistered farmer with a one-year imprisonment or KSh500,000 or both, for growing a scheduled crop. It is no coincidence that capitalist-funded organisations like Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) applaud the Irish Potato regulations as a new dawn for Kenyan farmers.

Through the Seed and Plant Varieties Act 2012, the government once again fails to protect farmers from capitalist exploitation. Part 1 of the Act defines selling as including barter, exchange and offering or exposing for a product for sale, taking away a farmer’s right to sell, share and exchange seed, a right that is recognised in the constitution.

Through the Seed and Plant Varieties Act 2012, the government once again fails to protect farmers from capitalist exploitation. Part 1 of the Act defines selling as including barter, exchange and offering or exposing for a product for sale, taking away a farmer’s right to sell, share and exchange seed, a right that is recognised in the constitution.

Part 2 section 3 of the Act prohibits the sale of uncertified seed. The good old practice of selling and sharing seeds is further criminalised in section 7(5) which requires only seed appearing in the Variety Index or the National Variety List to be sold. This limits farmers from selling their varieties which they have been sharing, exchanging and selling for generations. Moreover, this automatically means that farmers selling their seed varieties are committing an offence if such varieties are not listed in the index.

Further, section 18 part 4 of this act allows for the discovery of a plant variety whether growing in the wild or occurring as a genetic variant, whether artificially induced or not. This section allows for the discovery of farmers’ indigenous seeds by multinational corporations keen to patent them for profit.

It is no coincidence that capitalist-funded organisations like Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) applaud the Irish Potato regulations as a new dawn for Kenyan farmers.

The implication here is that since farmers’ seed varieties are not registered or owned by anyone, anybody can obtain the seeds of any crop variety, apply for their registration and claim their “discovery”. Farmers who have been conserving and reusing the “discovered” seeds will then lose the right to continue doing so and they will be required to pay royalties to the new “owners” of these seeds.

This act contravenes certain provisions of the constitution, in particular Article 11 (3) (b) of the Kenya Constitution 2010 which states that parliament shall enact legislation to recognise and protect the ownership of indigenous seeds and plant varieties, their genetic and diverse characteristics and their use by the communities of Kenya.

Foreign laws

The parliament has forfeited its obligation to enact laws that protect and enhance our intellectual property rights over the indigenous knowledge of the biodiversity and the genetic resources of Kenyan communities as mandated by Article 69 (1) (a) of the Kenyan constitution. It has allowed external actors to pirate local resources and trample indigenous rights.

Patenting indigenous seeds, barring farmers from keeping bees, and regulating the growing and selling of animal feed and potatoes is theft of the commons. The government is in cahoots with large corporations determined to kill the smallholder farmers’ sources of livelihood while singing about food security being part of the Big Four Agenda.

What sense does it make to frustrate smallholder farmers who grow 75 per cent of our food to serve the interests of imperialist multinational corporations keen on holding our farmers at ransom through abhorrent fines?

What sense does it make to frustrate smallholder farmers who grow 75 per cent of our food to serve the interests of imperialist multinational corporations keen on holding our farmers at ransom through abhorrent fines?

Patenting indigenous seeds, barring farmers from keeping bees, and regulating the growing and selling of animal feed and potatoes is theft of the commons.

It is time to reclaim and protect the commons that our communities have for a very long time thrived on. In her book Reclaiming the commons Dr Vandana Shiva points out that indigenous communities, including farmers, co-create and co-evolve biodiversity with nature, practises that have seen them overcome ecological challenges for generations. Our policies, plans and laws need to protect these practices for posterity.

Our parliamentarians should endeavour to defend our biodiversity, indigenous cultures and national systems – reclaiming the commons. We need policies that will allow farmers to produce food using indigenous seeds that are readily available and that they can be share amongst themselves. We need policies that will allow farmers to produce safer and more healthy food in an environmentally safe way, not punitive policies designed to eliminate farmers and have our food system controlled by corporations out to make profits at the expense of our health and our environment.

Support The Elephant.

The Elephant is helping to build a truly public platform, while producing consistent, quality investigations, opinions and analysis. The Elephant cannot survive and grow without your participation. Now, more than ever, it is vital for The Elephant to reach as many people as possible.

Your support helps protect The Elephant's independence and it means we can continue keeping the democratic space free, open and robust. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our collective future.

Data Stories

Tech Disruption in the Agricultural Sector

The future of farming in Kenya counties, whether in knowledge sharing, collaborations, funding, or market access primarily lies in the farmer’s abilities to harness the respective strengths of the available and emerging Disruptive Agricultural Technologies. As the tech-platforms become cheaper, more available and affordable farmers yield and fortunes will likely inch upwards.

Disruptive technologies in agriculture (DATs) have been in Kenya since the early 1900s and can simply be defined as the digital and technical innovations that enable farmers and agri-firms to increase their productivity, efficiency, and competitive edge.

These platforms essentially help local farmers make more precise decisions about resource use through accurate, timely, and location-specific price, weather predictions. The agronomic data and information that they provide in Kenya is becoming increasingly important in the context of climate change. Besides, leveling the playing field, it can make small-scale or local marginalized farmers in Kenya to be more competitive.

Sophisticated off-line digital agri-tech can provide opportunities even in poorly-connected rural contexts, or with marginalized groups who have lower access to information and markets. In short, Disruptive Agricultural Technologies (DATs) are overturning the sector status quo.

Some of the key disruptive technologies in agriculture (DAT’s) include Waterwatch Cooperative in Kenya (Real-time alert system), Tulaa and Farmshine (Digital platform for finding buyers and linking buyers and sellers).

There is also Agri-wallet (platform for input credit/e-wallets/insurance products), dutch-based Agrocares operating in Kenya and Ujuzi Kilimo (portable soil testers, satellite images, remote sensing) as well as SunCulture (solar-powered irrigation pumps)

These platforms have helped to facilitate access to local markets in counties such as Makueni and West Pokot, improve nutritional outcomes, and enhance resilience to climate change. Disruptive agricultural technologies are designed to help stakeholders by reducing the costs of linking various actors of the agri-food system both within and across countries through faster provision, processing, and analyzing of large amounts of data.

The Disruptive Agricultural Technologies Landscape

Over 75% of Disruptive Agricultural Technologies are digital. The remaining 25% of non-digital are either focused on energy (solar), or producers/suppliers of bio-products for agriculture.

Approximately 32% of the Disruptive Agricultural Technologies aim to enhance agricultural productivity, 26% are working to improve market linkages, 23% are engaged in data analytics, and another 15% are working on financial inclusion.

According to a 2019 World Bank report, Kenya has become a leading agri-tech hub with nearly 60 scalable Disruptive Agricultural Technologies (DATs) operational in the country, followed by South Africa and Nigeria. Kenya is said to have the third largest technology incubation and acceleration hub in the region. Examples of those technologies in Kenya include: Data-connected devices which use ICT to collect, store, and analyze data. This includes GPS, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. The Africa’s Regional Data Cube hosted in Nairobi,Kenya is a tool that helps various countries address issues related to agriculture, water, and sanitation.

The use of robotics and automation in farming in Kenya has gained widespread acceptance. For instance, drones are used to monitor and improve the efficiency of agricultural operations and its usage is governed by the Civil Aviation Act.

Majority of farmers in Kenya are smallholder farmers and having access to Disruptive agricultural technologies helps even the competition with medium and large scale farmers as tools are created for both low and high connectivity areas.

Over 83 percent of Disruptive agricultural technologies are e-marketplaces that do not require high connectivity. Example is Twiga Foods whose digital platform connects retailers and food manufacturers, delivering a streamlined and efficient supply chain.

Kenya’s financial sector is characterized by a robust mobile money ecosystem (MPESA) with over 70 percent of the population using mobile money regularly which increases its potential for farming for smallholder farmers.

Despite that one of the biggest challenges facing the agriculture sector in Kenya is access to finance. This is largely due to the high risk of loaning to small holder farmers. FinTech apps use alternative data and machine learning to improve the credit scoring of smallholder farmers.

These apps help minimize the gap between the demand for credit and the supply of financing for smallholder farmers. Kenya is a hotspot for agricultural apps. There are numerous organizations working on developing digital solutions that combine precision farming with remote sensing data.

Connectivity and Adoption of DATSs

A significant number of the existing digital tools and technologies can be utilized in areas with low network to improve the productivity of the agriculture sector. Despite the increasing number of mobile phone users in Kenya, the penetration rate among smallholder farmers remains relatively low.

It may be difficult for many of these smallholder farmers to adopt Disruptive agricultural technologies (DATs) due to the high costs, complexity and capabilities required. Meanwhile for large scale farmers, the DATs highly boost their productivity, especially if they have already developed the capabilities in-house to accelerate adoption of these tech platforms. Therefore, from the onset, we need to understand who uses the technology and the implications of this.

Kenya has a well-established start-up ecosystem, made up of mostly young, adaptive and brilliant innovators who are leveraging low-cost digital platforms. This is coupled with funding from international donors and incubation activities address agricultural value-chain issues. There is a mix of actors for Disruptive agricultural technologies depending on the categorization of the technology.

This ranges from DATS that support creation, facilitate adoption and oversee diffusion of innovation.

These actors need strong and cohesive ties, both between, the regulatory bodies, farmers, county leaders, financiers, state agencies, and fellow developers. The nature of the collaborations could be cohesive and cooperative, where all the local actors have shared goals, to fragmented, where not all actors are on board, causing resistance and slowing down the process.

Despite a myriad challenges these radical and innovative (DATs) are revolutionizing and changing the farming landscape in the counties and working with the Ministry of Agriculture using technologies to deliver agricultural services more efficiently and accountable.

The future of farming in Kenya counties whether in knowledge sharing, collaborations, funding, or market access primarily lies in the farmer’s abilities to harness the respective strengths of the available and emerging Disruptive Agricultural Technologies. As the tech-platforms become cheaper, more available and affordable farmers yield and fortunes will likely inch upwards.

–

This article is part of The Elephant Food Edition Series done in collaboration with Route to Food Initiative (RTFI). Views expressed in the article are not necessarily those of the RTFI.

Data Stories

Revealed: Majority of US Voters Support Patent Waiver on COVID-19 Vaccines

Shock poll reveals majority support for Joe Biden to suspend TRIPS and support global vaccination.

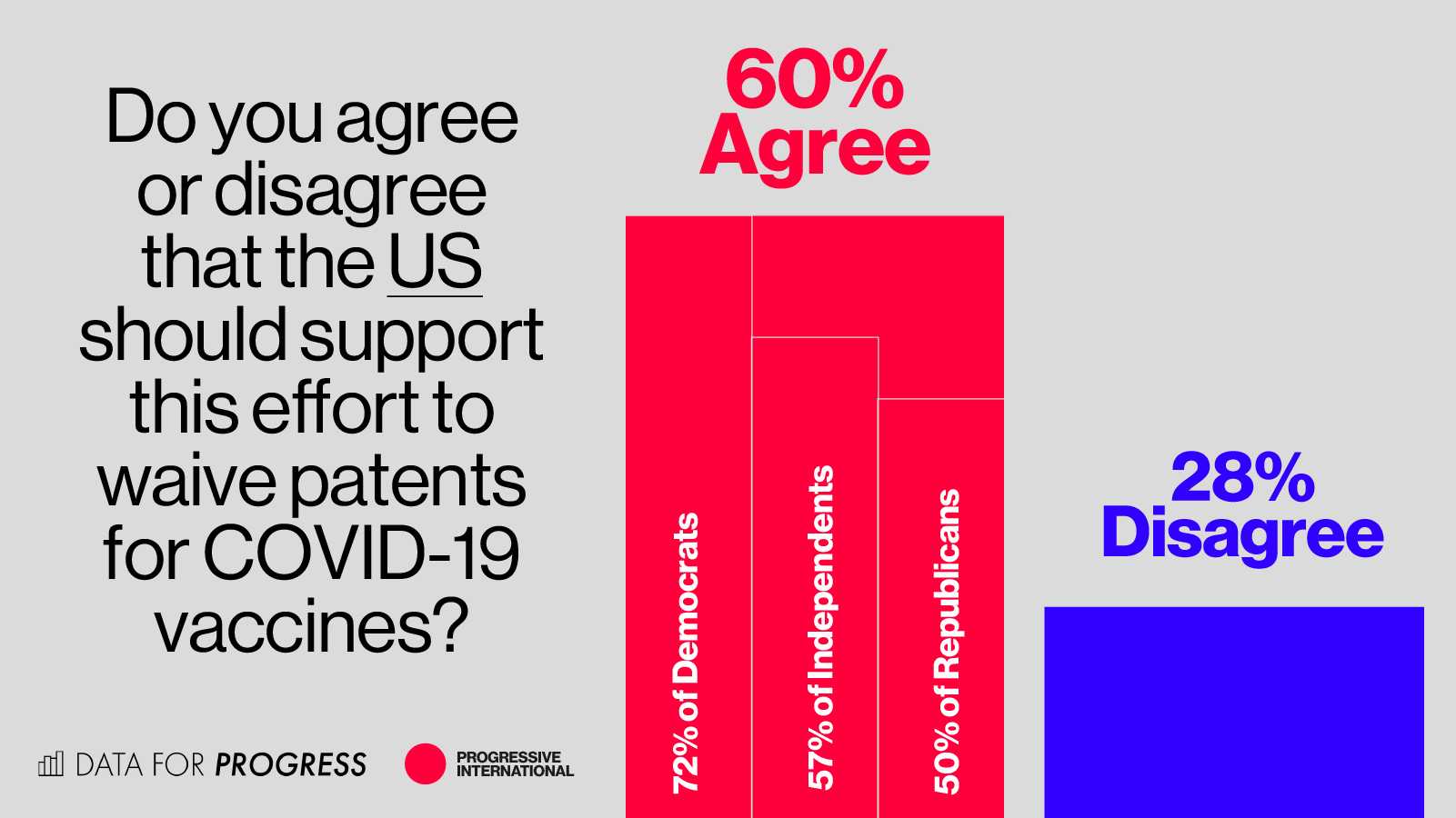

A new poll finds that 60% of US voters want President Joe Biden to endorse the motion by more than 100 lower- and middle-income countries to temporarily waive patent protections on Covid-19 vaccines at the World Trade Organization. Only 28% disagreed.

The survey, carried out by Data for Progress and the Progressive International, shows a super majority of 72% registered Democrats want Biden to temporarily waive patent barriers to speed vaccine roll out and reduce costs for developing nations. Even registered Republicans support the action by margin of 50% in favor to 36% opposed.

The new polling shows that “there is a popular mandate from the US American people to put human life and economic recovery ahead of corporate profits and a broken intellectual property system,” said David Adler, the general coordinator of the Progressive International. Burcu Kilic, research director of the access to medicines program at Public Citizen and member of Progressive International’s Council, called on Biden to “listen to Americans who put him in power” and “do the right thing.”

Due to WTO intellectual property rules, countries are barred from producing the current leading approved vaccines, including US-produced Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. In October of 2020, South Africa and India presented the WTO with a proposal to temporarily waive these rules for the duration of the pandemic so that vaccines can be manufactured across different countries, increasing their availability, reducing their cost and ensuring that they are delivered to everyone on earth as quickly as possible.

Due to WTO intellectual property rules, countries are barred from producing the current leading approved vaccines, including US-produced Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. In October of 2020, South Africa and India presented the WTO with a proposal to temporarily waive these rules for the duration of the pandemic so that vaccines can be manufactured across different countries, increasing their availability, reducing their cost and ensuring that they are delivered to everyone on earth as quickly as possible.

In the absence of the waiver, the current manufacturing and distribution rates are unlikely to stem the pandemic’s momentum, especially as new variants, which are more infectious and seem to evade the acquired immunity from prior infection or from the current vaccines, continue to emerge. The US under President Trump joined other richer nations to block them.

The shock poll reveals a level of public support for intellectual property waivers that will likely add to growing congressional pressure on Biden to join those pushing to save lives through a global vaccination drive. Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky is working on a letter to the president to which Schakowsky says more than 60 lawmakers have added their signature, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Senator Bernie Sanders, Chair of the Senate Budget Committee, responded to the poll saying the US should be “leading the global effort to end the coronavirus pandemic.” According to Sanders, “a temporary WTO waiver, which would enable the transfer of vaccine technologies to poorer countries, is a good way to do that.”

Responding to the new poll, Representative Ilhan Omar called on Biden to “support a waiver to boost the production of vaccines, treatment and tests worldwide,” arguing that it was “not just an issue of basic morality, but of public health.”

Adler argues, “US Americans know rigged rules to prop up big pharma’s profits are not in their interest. The longer the virus has to spread, the more it can mutate and become vaccine-resistant. Covid-19 anywhere is a threat to public health and economic wellbeing everywhere. If intellectual property restrictions are not lifted, the pandemic will go on for longer, killing more people and damaging more livelihoods.”

The threat to the Global South from vaccine apartheid is a “death sentence for millions around the world—and it is because giant pharmaceutical corporations would rather maximize profit than provide vaccines to people who need it,” according to Omar.

Sanders agrees, saying “the bottom line is, the faster we help vaccinate the global population, the safer we will all be. That should be our number one priority, not maximizing the profits of pharmaceutical companies and their shareholders.”

Data Stories

Erosion of Civil and Political Rights in Africa: Ibrahim Index (IIAG) 2020 Report

The IIAG report concludes that 2020 was a terrible year for democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa where political freedoms have deteriorated over the last decade, with citizens having less freedom to assemble in 2019 than they did in 2010.

Is there a link between democratic liberties and human rights on one hand, and good governance and economic progress on the other? Ever since the fall of the Berlin wall, a thirty-year orthodoxy has argued that the former are indispensable to the latter. However, a report by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation raises questions about this.

According to the 2020 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), political freedoms across the African continent have continued to deteriorate over the last decade, with citizens having less freedom to assemble in 2019 than they did in 2010, and the trend has accelerated since 2015. On the other hand, countries’ scores in the Human Development and Foundations for Economic Opportunity categories have improved, with the biggest strides being made in infrastructure and health.

According to the 2020 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), political freedoms across the African continent have continued to deteriorate over the last decade, with citizens having less freedom to assemble in 2019 than they did in 2010, and the trend has accelerated since 2015. On the other hand, countries’ scores in the Human Development and Foundations for Economic Opportunity categories have improved, with the biggest strides being made in infrastructure and health.

And although African countries made progress in overall governance during the last decade, the rate of improvement has slowed down over the last five years which explains the below average score in 2019.

Does this mean that the Chinese model of development—which views human and political rights as a barrier to economic progress—is supplanting the Western model, which proposes that they should go hand-in-hand on the continent?

Andrea Ngombet, a human rights activist and former presidential candidate in the Republic of Congo, says that there is more to it than that.

“To be completely honest, the combination of Chinese money, Western companies’ corruption and African autocrats’ lust for power are the causes of the retreat of democracy. All of them have no interest in a democratic Africa with tax to pay, protected workers and protected environment,” he said.

When asked why democracy is in retreat in African countries, Ngombet explained, “China [reinforces] African autocrats with cheap loans which they use for clientelism and populist projects. As the loans are without any democratic conditions, it allows the autocrats to resist the civil society pressure for democracy and accountability.”

Ngombet also explains that, “When looking at the quality of economic growth, it comes with bad loans over authoritarian regimes and those loans finance unprogressive infrastructure.”

The IIAG report shows that Gambia—the most improved of the 54 African countries—experienced the most changes after 2016 when Yahya Jammeh’s repressive 22-year-reign ended, although the current regime still faces challenges in enforcing environmental policies and in the areas of quality of education, law enforcement and compliance with international health regulations.

Source: 2020 Ibrahim’s Index

The study, whose goal was to help further the conversation on governance in the continent and assess current and emerging trends, analysed 237 variables from 40 different sources. It revealed that African countries are performing the worst in the Participation, Rights & Inclusion category (with an overall average score of 46.2 in 2019). This decline is caused by a deteriorating security situation and an increasingly “precarious environment for human rights and civic participation”.

Source: 2020 Ibrahim’s Index

Nearly half the countries on the continent had less freedom to associate and assemble and a shrinking space for political pluralism and civil society at the close of the 2010s than they had at the beginning of the decade. This was the continuation of a diminution of civil liberties in the second half of the 2000s following improvements in the first half of that decade.

In particular, compared to the country’s scores in 2010, Kenya’s scores for freedom of association and assembly as well as media freedom fell by over 20 per cent from 2015 while the indicators for transparency and accountability, as well as anti-corruption mechanisms also fell during the same period.

However, the Ibrahim report does indicate that the indicators for digital access, energy access, infrastructure and human resources in the education sector have shown a marked improvement under the current Kenyan regime. This is despite a huge debt burden and numerous unresolved corruption cases.

Increased restrictions have been placed on the establishment and operations of civil society and non-governmental organisations which have also experienced higher cases of repression and persecution in most African countries. Political parties have experienced reduced access to state-owned media and public financing for their campaigns which has curtailed their operations.

Democratic elections, the only indicator that had shown a steady improvement since 2010, took a downward spiral in 2015. Election results in countries such as Uganda, Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire, Central Africa Republic, Gabon and the Democratic Republic of Congo have been consistently disputed as the integrity of the electoral process and the independent functioning of election-monitoring bodies have been compromised.

“You can not have democratic elections in the absence of strong institutions such as Independent judiciary, a parliament that is not completely corrupted, independent press, civil societies to monitor and people to engage citizens ahead of elections and inform them by helping them understand democracy rest on their shoulders, governance rests on their shoulder, and not the person that they’ll vote in for,” Tutu Alicante, executive director at EG Justice in Equatorial Guinea explains.

“It is us that [create] democracy. It is us that [create] governance and all the security, rule of law and human development and not the person [who] as soon as elected will focus on their pockets and family.”

Countries such as Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Chad, DRC, Rwanda and Cameroon that have scored dismally in the participation, rights and inclusion category, have all been under the rule of African leaders who have clung on to power.

These findings resonate with those of the 2020 Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index which placed Chad, Central African Republic and Democratic Republic of Congo at the bottom of the rankings in democracy in Africa, measured by electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture and civil liberties.

It may be encouraging for citizens of Djibouti, Somalia and Eswatini that although their countries are among those with the least scores in terms of participation, they have registered improvements over the decade.

“Full democratic participation is essential for the development in our society. In Africa if we are thinking about Ubuntu as a basic principle of our society, then clearly democracy is needed in a way in which we all participate in order for us as a society to rise up,” Tutu adds.

Egypt has performed exceedingly well in the score for infrastructure (80/100), and health development indicators (all above 60/100) yet, surprisingly, the country is the third least performing country in Africa, after Burundi and Eritrea—with a score of 7.9/100—when it comes to participation as a principal of good governance.

Egypt has been under dictatorship since the Arab Spring overthrew Hosni Mubarak in 2011. The government has authorised the blocking of close to 500 websites belonging to news outlets, blogs and human rights organisations, and in 2017 blocked the use of internet tools such as VPNs.

Other countries that have experienced drastic internet shutdowns, legal digital restrictions and surveillance include Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Morocco, Benin, Rwanda, Morocco, DRC and Uganda. This often happens during electioneering periods or citizen protests despite “freedom of expression being a fundamental human right enshrined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the cornerstone of democracy”, according to UNESCO, an organisation to which most of these countries belong.

Countries that have managed to transition from dictatorships or civil wars, such as Sierra Leone, Gambia, Togo, Angola and Sudan manifest increasing improvement in their citizens’ access to the fundamental civil rights.

African governments are slowly becoming more inclusive and equal in the provision of public services and the creation of socioeconomic opportunities.

Kenya and Somalia have seen the most improvements under the Gender indicator. Although Kenya has faced difficulties in passing the two-thirds gender rule (leading former Chief Justice Maraga to direct that the president dissolve parliament), it has made impressive strides in providing social-economic opportunities for women and in the representation of women in the executive even though gender equality in civil rights has declined substantially.

In contrast, women in South Africa, Ghana and Equatorial Guinea are enjoying less protection against gender violence.

Is it a question of striking a delicate balance between good overall governance and maintaining the economic growth and security of a country? Or might too much freedom lead to coups and mutiny?

The EUI Democracy report ranked Mali and Burkina Faso—both of which do not have full control over their territories and experience rampant insecurity precipitated by jihadist insurgents—as the worst performing countries in West Africa in terms of democracy. They were downgraded from “hybrid regime” to “authoritarian regime”. The report concludes that overall it was a terrible year for democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 31 countries were downgraded, eight stagnated and only five improved their scores.

It is an interesting phenomenon that, despite low scores in civil and political rights, the best scores are to be found in the Foundations for Economic Opportunity and Human Development categories with 20 countries having improved their governance score in these two areas, albeit at a slowed rate in the last five years. The biggest strides have been made in the Infrastructure and Health indicators, complemented by improvements in Environmental Sustainability.

More often than not, infrastructure and health projects are marred by allegations of corruption and lack of transparency. Yet, a correlation model run by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation shows that there is a strong and positive correlation between the overall governance score and specific indicators such as rule of law and justice, inclusion and equality, anti-corruption, transparency and accountability and business environment. Even though statisticians agree that “correlation does not imply causation”, this model indicates that countries with higher scores in those indicators also have higher overall governance scores.

Yuen Ang argues that “the idea that economic growth needs good governance and good governance needs economic growth takes us to a perennial chicken-and-egg debate” whereas Meles Zenawi has claimed “There is no direct relationship between economic growth and democracy historically or theoretically. Democracy is a good thing in and of itself irrespective of its impact on economic growth and my view is that in Africa most of our countries are extremely diverse that maybe the only option of keeping relationships within nations sane. Democracy may be the only viable option of keeping these diverse nations together, we need to democratise but not in order to grow, we need to democratise in order to survive as a united same nation.”

The 2020 IIAG report paints a picture of a continent that had long embarked on the road to decline in rights, civil society space and participation before it was hit by COVID-19. Even though Africa accounts for 3.5 per cent of the global reported COVID-19 deaths, the pandemic is now threatening hard-won gains in areas such as foundations for economic opportunity and human development.

-

Long Reads2 weeks ago

Long Reads2 weeks agoPan-Africanism and the Unfinished Tasks of Liberation and Social Emancipation: Taking Stock of 50 Years of African Independence

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoPlunder and Theft: Ways of the African Oligarchs

-

Op-Eds7 days ago

Op-Eds7 days agoPalestine and the Necessary Evils of Settler Colonialism

-

Op-Eds2 weeks ago

Op-Eds2 weeks agoWill Kenya’s Vision 2030 Megaprojects Bring the North in From the Cold?

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoNortheastern Kenya: Theatre of Al-Shabaab Operations

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoThe Whitewashing of Empire and Britain’s Radical Historical Amnesia

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoUganda’s Huge Fossil Fuel Venture Raises Fears of Environmental Damage

-

Long Reads7 days ago

Long Reads7 days agoReturn to the Land of Jilali: Reflections From Kenya’s Northern Frontier