Ideas

The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Raised Questions About Interdisciplinary Degrees

8 min read.Life and reality, in and of themselves, are already interdisciplinary. There is therefore need to heal Kenyan higher education so that it reflects life itself. Universities need to be communities where skills are taught in the classrooms for professionals to practice in society, but interdisciplinary thinking is practiced through collaboration facilitated by the institutional culture.

A few years ago, I noticed an interesting phenomenon in the profile of applicants for language faculty positions. A number of degree holders had studied, especially in the UK, language teaching, rather than linguistics or education. This meant that the interviews revealed gaps in the candidates’ theoretical and technical grasp of either field.

An additional phenomenon, which was more worrying, was that when we asked some about their PhD aspirations, some of the applicants were not interested in pursuing their discipline. Some wanted to go into development and related fields, others into the more attractive degrees like communication. More disturbing among the literature aspirants was that some were not familiar with the latest fiction and other artistic output by Kenyans.

Because of Kenya’s anti-intellectual culture rooted in colonial rule and post-independence autocracy, most Kenyans reading this will collapse into the age-old narrative that Kenyan universities are at their usual game of producing graduates with “useless degrees.” However, I will argue in this article that these gaps are not just structural, but also neoliberal and global.

My interest in this issue has been ongoing, but especially in my concern that key professions in Kenya are being overwhelmed by administrative bloat, where the bulk of decisions are made by people who do not have experience or training in the professional area they are making decisions about. But my concern recently got a boost when a recent conversation about the Covid-19 pandemic shut down when I mentioned the current debates about privatization of healthcare.

Another thing that struck me about the conversation was the faith in policy to fix structural problems. This faith is not unique to health. However, I find it interesting that in several cases, many of these policies are foreign or “international” (to remove the overt Euro-American provenance), and Kenyans take the assumptions about the policies for granted. As such, people get surprised when I question the policy itself, or its ability to resolve the problems which it is being offered to solve.

I therefore decided to sample the syllabi of postgraduate degrees in public health in universities in Kenya, UK and the US. Of key interest to me were

- Were these degrees for medical practitioners?

- Was there any unit that potentially tackles imperialism, capitalism and privatization as a health financing model; non-western forms of medicine; and history of imperialism and medicine in the global south?

In answer to the first question, the degrees were open to graduates not just from medicine, but from a wide range of disciplines. I am not against this in principle, but I am concerned that in a country like Kenya where business graduates have colonized the professions, this degree baptizes such graduates with health qualifications when they are not able to treat.

On the second question, none of the topics is explicitly addressed, but more interesting is that there is at least a unit or two on traditional economics and on management systems. With international pharmaceutical companies and financiers interested in commercializing health, the absence of units on racism, imperialism and neoliberalism raises a flag about the possibility that universities are creating a cohort of policy bureaucrats to infuse the neoliberal logic in public healthcare systems worldwide. This would explain the rise in such scholarships from Western government bodies to students in the global south.

And yet, if this pandemic has revealed anything, it is that health is a multi-faceted area that requires the cooperation of people with specialization in humanities, social sciences, the life sciences and physical sciences. In other words, every discipline has to be involved in discussions, knowledge and politics of health.

So why do I question interdisciplinary degrees like public health? Am I against interdisciplinary studies in principle?

Interdisciplinary degrees are a luxury

In every conversation where we are reminded how pathetic we Kenyan academics are, there is a mention of the need for interdisciplinary research. African scholars abroad also emphasize the need for African universities to introduce more interdisciplinary programmes and do more interdisciplinary research.

The problem is that advocates for interdisciplinary research do not address the culture of the Kenyan university as it now stands. These days, each discipline and department is a competitor, not a collaborator. We are all competing for student numbers to avoid the risk of being shut down or losing our jobs. That means that people whose disciplines sound job oriented, like media studies or conflict resolution, or even “public health,” attract more students than language, performing arts, history, political science or medicine. Departments would now rather create units in their departments that cover the necessary skills from traditional disciplines than allow their students to come study in the departments of traditional disciplines. Some faculty even go as far as telling their own students that the units are not available in sister departments.

To compound matters, the managerial overload in Kenyan universities means that the spontaneous interdisciplinary conversations among academics have basically died. Large class sizes mean that we can afford little time to chat and think. When we meet, we are meeting to trouble shoot inefficient systems, or to discuss administration matters such as how to fulfill the government’s regulation requirements or which new program would attract students.

This culture of self-consciousness and competition is carried into academic conferences. We don’t read or discuss each others’ work, partly because, as I noticed when I was researching on education, our research agendas are dominated by government policy and not by public conversation or challenges.

With universities divided like this into silos, students can graduate without ever hearing people from disciplines outside their degrees. The days when Anyang’ Nyong’o was a political science student publishing poetry, or when Kivutha Kibwana was a law student writing plays, have gone. For those of us in the arts, the bulk of our students are now in our classes just to meet the bureaucratic requirements and to sign the attendance sheet. And when we try to tie your discipline to actual issues in society or other disciplines, the students feel that we are deviating from the syllabus. We are asking them to think, and university education is not for their minds. University education is for employers.

This situation has been brought about by the failure of Kenyan academics to challenge the language of the market imposed by government and private sector, who often accuse universities of offering programmes that are “too theoretical” and have no practical use in the market.

But a more serious problem is now gaining root. We have less and less workers in the fundamental areas, because Kenyans are shunning arts and science-based courses, and going for interdisciplinary degrees, in the belief that they will pursue careers as policy makers in either government, business or NGO sector.

This scenario has produced the frustration of professionals in the arts and sciences. As a literary scholar, for example, I was recently frustrated by journalism which collapsed melodrama into investigative reporting. Mordecai Ogada, an ecologist, writes of the strange situation of seeking an internship at Kenya Wildlife Service, and being told by no less than the research director, that KWS did not need research scientists but wildlife managers (who are often trained in business schools). Some time back, a medical doctor expressed frustration with public health graduates, saying that their top applicant for a job “couldn’t differentiate between air borne diseases and water borne diseases. Or give an example of a bacterial STI.”

Interdisciplinary courses are failing our students because they are teaching students to integrate and apply knowledge which the students have not mastered in the first place. It is my opinion that we need a moratorium on these programs in Kenya, until such a time that we have enough health workers to treat, enough teachers to teach, and enough professionals to practice their skills in the field. Interdisciplinary fields are flooding the market with health professionals who can’t or have never treated, education bureaucrats who make policy that does not work in the classroom, and, as Ogada said, research officers who are basically revenue collection agents.

Disciplinary healing

In his book Disciplinary Decadence: Living Thought in Trying Times, philosopher Lewis Gordon addresses this silo mentality of university departments, noting that disciplines have collapsed on themselves and stopped talking to each other. Instead, he notes, everybody attacks the other for not being them. For instance, philosophers attack religion scholars for not being philosophical, literature scholars attack medics for not being literary, and medics attack artists for not being medical. The economists attack everybody else for not being entrepreneurial. What is lacking, Gordon argues, is the recognition that education is necessarily interdisciplinary, and requires conversations across disciplines.

These silos need to be replaced with the “teleological suspension” of our subject areas in our pursuit of knowledge. Teleological suspension, Gordon explains, “is when a discipline suspends its own centering because of a commitment to questions greater than the discipline itself.” We implement this suspension because it is more important to answer real life questions using knowledge from various disciplines, than it is to be a stickler for rules and insist that a question can only be answered by one’s own discipline, and that people who are not trained in that area cannot participate in the conversation. Just like we suspend reality when we read fiction or watch a play, we professionals and academics should be able to suspend our professional titles and trainings as a doctor, philosopher, literary scholar, scientist or anthropologist, and be able to talk to people in other disciplines over the common issues confronting all of us.

What is lacking in Kenya is not graduates. It’s real education in its true interdisciplinary character. Kenyans are unable to talk with each other across the disciplines because they have been compartmentalized by the market logic imposed by the private sector, enforced by the government and popularized by the media.

We need to return to true education, because education is the space in which society suspends disciplinary boundaries and discusses real life issues. Instead of bureaucratizing interdisciplinary-ness through degrees, we should reconstruct the university to become a community where the public, not just academics and students, come together from across the disciplines to discuss issues facing all of us. Education needs to return to being the public space through which, as Gordon says, “the unpredictable can leap forth and the creative can shine.”

Achieving such an education system requires the following:

- 1. Constant debunking of the market logic that is imposed on education. Academics need to stop bowing to private sector’s demands for employees who subsidize company profits by paying for their own specialized training. In its demands for work-ready graduates, the private sector behaves as if the entire society must revolve around it. We need to resist this abuse.

- A university environment that creates the opportunity for conversation and human interaction, because the supremacy wars between departments and disciplines will have ended together with the market logic. With more academic faculty and a lower teaching load, departments can invite people outside their discipline to give lectures and debates on real-life issues which can be attended by students and the general public. The discussions and questions from the audience will nurture interdisciplinary thinking without universities needing to invent interdisciplinary degrees for the students. And students will get to build interprofessional relationships with their classmates, relationships which they can use once they are working in the larger society.

- Revive theoretical studies in the university. The popular idea of “theory” as irrelevant thinking has scared academics away from theoretical engagement and to interdisciplinary degrees to display their “relevance.” However, theory is, simplistically put, a story, no matter which discipline the story is told from. Different disciplines unite when they discuss theory. For instance, the work by Frantz Fanon is relevant to his professional training in medicine, to education, literature, politics, psychology, environmental studies and so many other disciplines. And yet Fanon is little spoken about in Kenyan academic spaces.

The war against theory, Gordon says, is in reality a war against truth and reality. In fact, one striking feature of the public health programs I surveyed is that there is no unit dedicated to theory. How are the students able to talk across diversity of disciplinary backgrounds with no theory?

Life and reality, in and of themselves, are already interdisciplinary. There is therefore need to heal Kenyan higher education so that it reflects life itself. Universities need to be communities where skills are taught in the classrooms for professionals to practice in society, but interdisciplinary thinking is practiced through collaboration facilitated by the institutional culture. With only 2% of the Kenyan population having attended university, and with the number of health workers way, way below minimum per population, we cannot afford to pour resources into interdisciplinary degrees, especially not for health.

Let us emulate the Cubans and train and employ more health workers who actually treat Kenyans, and who can resist being outnumbered and outpowered by bureaucrats implementing the neoliberal and bureaucratic logic that is destroying our healthcare. The health workers can then team up with the “useless” graduates in the arts and social sciences to come up with an experience-based, technically robust and human response to health challenges such as pandemics. That way, we would not rely on bureaucratic and “policy” responses that are proving to be more neoliberal than anything else.

Support The Elephant.

The Elephant is helping to build a truly public platform, while producing consistent, quality investigations, opinions and analysis. The Elephant cannot survive and grow without your participation. Now, more than ever, it is vital for The Elephant to reach as many people as possible.

Your support helps protect The Elephant's independence and it means we can continue keeping the democratic space free, open and robust. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our collective future.

Ideas

The World Seen Anew Through Dani Nabudere’s Eyes

If Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s notion of decolonisation incorporates the linguistic perspective, Dani Nabudere’s project, on the other hand, takes in the fundamental philosophical component as an indispensable foundation, a call to rebuild self, society, culture and civilisation from the very beginning.

I first met the distinguished Ugandan scholar Dani Nabudere in 2011, the very year he passed. I had been co-organiser of a conference held in Pretoria, South Africa, to mark the 50th anniversary of the African Union (formerly the Organisation of African Unity — OAU). The conference had been largely organised and funded by Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, the Thabo Mbeki Leadership Institute, University of South Africa, the National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF) and the Department of Science and Technology, South Africa.

Nabudere was a sprightly 79-year-old, alert, engaged and lively in conversation.

Before the Pretoria meeting, I had actually seen him in action at a conference held in Cairo in 2005 under the auspices of the African Association of Political Science. This was a huge international event with delegates from all over the world and there had been no opportunity to engage with him one-on-one; buying a number of his writings was as close as I got to Nabudere.

Cairo is a metropolis replete with history, culture and countless visual delights. In the permanent whirl of exciting people, cultural riches and hot dry air, not meeting Nabudere then did not seem like such a great loss.

The visit to the art shops that target tourists was an experience in advanced marketing. I bought four scrolls depicting ancient Egyptian heroes, symbols and hieroglyphics. An unusually vibrant woman ensured that I did not leave her shop empty-handed.

The trip to the famed pyramids was nothing short of awe-inspiring. I had gone with an overly cautious delegate from Nigeria who simply did not get the magic of the magnificent edifices, was not willing to explore the mysteries of the inner vaults or take any chances digging deeper below the surface. He saw his holding back as absolute good sense rather than an almost criminal failure of the imagination.

I had tripped and almost suffered a bad fall during our initial explorations at the base of the pyramids and that provided him with the awful excuse not to venture further. What was the point of venturing forth if it could end with a broken leg or worse?

But the Pretoria meeting with Nabudere was very different. It was held at St Georges Hotel in Irene, outside Pretoria, in secluded and serene environs. Also, because it was a slightly smaller event than the Cairo conference, it was possible to really speak with Nabudere as opposed to only seeing him from afar.

During the 2000s, Nabudere had studied and written extensively about the events in the Great Lakes Region (GLR) in the aftermath of Mobutu Sese Seko’s ousting as the paramount ruler of what was then Zaire. Nabudere’s writings on the topic are impassioned, lively and clearly of an activist nature. He was outraged by the rape and plunder of the region by unscrupulous Western speculators and mercenaries out for loot and illicit gain.

But by the end of the decade, Nabudere had found another equally fascinating subject of interest: Afrikology. Afrikology is concerned with the primary retrieval of the lost, submerged and obscured knowledges of ancient Egypt (Kemet), Nubia and Meroe, all of which are great civilisations of ancient Africa.

In Nabudere’s view, contemporary human existence is irreparably fractured, alienating and thus ultimately dissatisfying. Part of the reason for this sorry state of affairs is that ancient Greek scholars who visited ancient Egypt in search of knowledge, culture and civilization misinterpreted and misappropriated what they were given or had been able discover.

The first effect of this gross misappropriation led to the creation of a philosophical pseudo-problem known as the mind/body dichotomy, which is a central motif in contemporary philosophy. Nabudere argues that this motif is both false and misleading. There is nothing, he asserts, that exists as the mind/body problem which has in turn caused societal fragmentation, alienation and false thinking in current human existence. Nabudere then makes his boldest conceptual move, which is to call for a return to ancient Kemetian thought that he believed to be imbued with therapeutic epistemological holism.

But when I spoke with Nabudere during breaks in between conference sessions, he did not dwell on these revolutionary ideas. Instead, he struck me as a seasoned village elder more concerned with indigenous systems of knowledge uncorrupted by Western methods. He freely shared remedies for bites from venomous snakes. We also spoke about the difficulties in pursuing bold independent thought in the current academic environment. And then he indicated that he wanted us to continue our conversations by email.

Nabudere sent me a flurry of unpublished manuscripts. One would eventually be published as Afrikology, Philosophy and Wholeness: An Epistemology in 2011. Afrikology and Transdisciplinarity: A Restorative Epistemology was released the following year. Nabudere argues that “Afrikology seeks to retrace the evolution of knowledge and wisdom from its source to the current epistemologies, and to try and situate them in their historical and cultural contexts, especially with a view to establishing a new science for generating and accessing knowledge for sustainable use.”

I, on my part, began a journey that took me from Nabudere to Cheikh Anta Diop to Molefi Kete Asante and back. There are conceptual links between Afrikology and Afrocentricity. Not only did these philosophies need to be re-discovered, there were entire civilisations waiting to be explored as broken, fragmented selves sought collective healing.

Before he passed, Nabudere founded the Marcus Garvey Pan-African University in Mbale, Uganda. Garvey, as we know, attempted to launch a “back to Africa” movement for the black people of the Americas living under the yoke of racial oppression. Of course, he angered the powers that be and was prosecuted, convicted and eventually deported from the United States back to his native Jamaica on trumped up charges of mail fraud.

Nabudere’s adoption of Garvey’s name for his institution speaks volumes. It demonstrates how serious he was about the project of epistemological decolonisation, an endeavour pursued in other ways by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, another great East African writer and thinker. wa Thiong’o makes language his focal point in order to restore epistemic truth and continuity. In his view, our attachment to European languages is the most obvious manifestation of our state of dependency and most chronically, our psychological unfreedom.

Not only did these philosophies need to be re-discovered, there were entire civilisations waiting to be explored as broken, fragmented selves sought collective healing.

Indeed, the range of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s project of decolonisation is a result of focused examination of the workings of colonialism and its accompanying effects. He began by questioning the neo-colonial educational arrangement in Kenya as far back as the late sixties when he was still a rather young scholar. In his important book Writers in Politics (1981), he asserts:

Let us not mince words. The truth is that the content of our syllabi, the approach to and presentation of the literature, the persons and the machinery for determining the choice of texts and their interpretation, were all an integral part of imperialism in its classical colonial phase, and they are today an integral part of the same imperialism but now in its neo-colonial phase..

wa Thiong’o goes on to examine the relationship between literature and society and how this linkage in turn radically affects a people’s cultural orientation. A central assertion of his is that “literature was used in the colonization of our people”. To transform this situation, it is then necessary to employ literature for the subversion of imperialism. Throughout Writers in Politics, wa Thiong’o maintains a decidedly Marxist ideological stance and so his analyses of the forces that control the economy, politics, education and culture are based upon the socialist conception of class and society.

In the early stages of his career, wa Thiong’o had reasoned:

For the last four hundred years, Africa has been part and parcel of the growth and development of world capitalism, no matter the degree of penetration of European capitalism in the interior. Europe has thriven, in the words of C.L.R. James, on the devastation of a continent and the brutal exploitation of millions, with great consequences on the economic political, cultural and literary spheres.

Colonialism gave way to neo-colonialism, which wa Thiong’o defines thus:

Neocolonialism . . . means the continued economic exploitation of Africa’s total resources and of Africa’s labour power by international monopoly capitalism through continued creation and encouragement of subservient weak capitalistic structures, captained or overseered by a native ruling class..

In turn, this compromised ruling class makes defence pacts and other unequal agreements with its former colonial overlords in order to secure its grip on political power. The underclass, for its part, is effectively alienated from the structures of power. wa Thiong’o urges that “we must insist on the primacy and centrality of African literature and the literature of African people in the West Indies and America” so as to present a unified front against the cultural and psychological effects of global imperialism. In this regard, the oral literature of our people is of particular importance. Furthermore, he argues that, “where we import literature from outside, it should be relevant to our situation. It should be the literature that treats of historical situations, historical struggles, similar to our own.”

This is a point wa Thiong’o stresses repeatedly in his numerous texts, and one reason that his notion of decolonisation can be recognised to be not only radical but also quite expansive in the way he views the world. Indeed, his understanding of decolonisation has an undoubtedly global dimension, as would be seen later. Furthermore, wa Thiong’o agrees with Fanon that decolonisation is a radical process in which the oppressed and disenfranchised classes all over the world would have to “adopt a scientific materialistic world outlook on nature, human society and human thought”. Hence it is not enough to indulge in “a glorification of an ossified past”. Indeed, he is critical of the somewhat unproductive aspects of traditional societies, as well as of imperialism. As he writes, “The embrace of western imperialism led by America’s finance capitalism is total (economic, political, cultural); and of necessity our struggle against it must be total. Literature and writers cannot be exempted from the battlefield.”

Our attachment to European languages is the most obvious manifestation of our state of dependency and most chronically, our psychological unfreedom.

Since wa Thiong’o’s project of decolonisation is concerned with imperialism on a global scale, he stresses the need for oppressed people all over the world to unite in order to confront it. In other words, if the dynamics of imperialism are global in nature then the counter-power to them should equally be global in its articulation.

However, the task of true psychological and epistemic liberation is first and foremost philosophical. In the recent past in Africa, it was an endeavour that was usurped by charlatans and political opportunists who managed to recast it as a crude politics of nativism or indigeneity as occurred in Mobutu’s Zaire.

If Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s notion of decolonisation incorporates the linguistic perspective, Nabudere’s project, on the other hand, takes in the fundamental philosophical component as an indispensable foundation. It is in essence a call to rebuild self, society, culture and civilisation from the very beginning. It is also a repudiation of contemporary human culture in its entirety as it is incomplete, truncated and therefore profoundly misguided.

It is also in every sense a call to arms, an annihilation of the false consciousness and civilisation that veil themselves in a cloak of authenticity. In fact, Nabudere proceeds to question our current genetic state of being which might have undergone a fatally inappropriate mutation. And in order to institute a crucial re-alignment, we must reject everything about ourselves, our society and contemporary culture. Nothing could be more radical.

To imagine that such radical ideas had been formulated in the distinguished head of the old, patient and pleasant man I met with in Pretoria a few times. He perhaps did not bother to share them with me then because he knew that he would eventually send me his manuscripts. In this way, he had bridged several disparate worlds: ancient and contemporary, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity, traditional griot and modern-day polymath. Moreover, he had promoted a tradition our modern institutions would find too off-kilter to handle because it had been bold enough to question their existence. And being a custodian of gnostic or esoteric knowledge, when he died, it was akin to a giant baobab falling in a forest. Without a successful passing of the torch, a huge vacuum would definitely be left in the culture, one that has been denied, vilified and suppressed for centuries. First, by external detractors and then subsequently, by the children of the Dark Continent themselves, caught up and invariably obscured, stunted and masticated by the paroxysms of modernity.

Ideas

COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates in the Light of Public Health Ethics

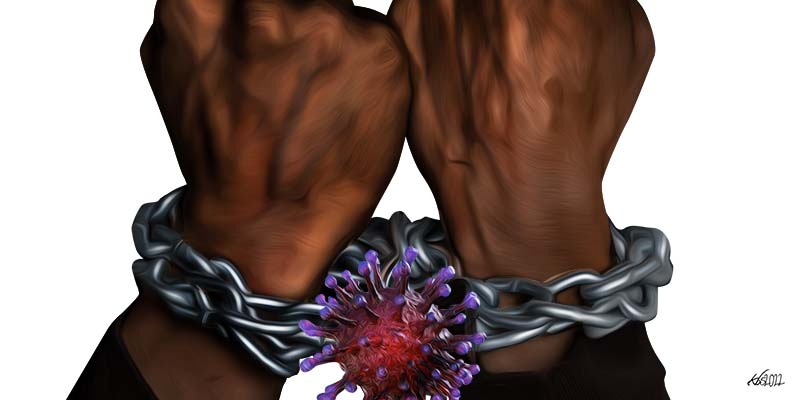

Vaccine mandates are instances of state overreach, as they violate human dignity, human agency and human rights, thereby eroding the very foundation of democratic society.

In the wake of COVID-19 vaccine mandates (in which governments require citizens to be vaccinated regardless of their preferences), moral issues need to take centre stage. This is because we human beings are not simply matter, but also rational consciousness – we think and feel, and so it matters how we treat other people, and also how they treat us. Morality is the judging of human action in terms of rightness and wrongness, and human traits of character in terms of virtue (desirable quality) and vice (undesirable quality). While in everyday usage “morality” and “ethics” are considered to mean one and the same thing, we also use the term “ethics” to refer to philosophical reflections on morality, and this latter sense is my focus here.

Countries usually have various public health authorities that issue directives that should ideally enhance the overall well-being of their citizens. In Kenya, for example, the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS), the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB), and the Ministry of Health are among such bodies. Thus, the various COVID-19 protocols from the Ministry of Health are public health measures rather than medical care ones. At the global level, public health measures are currently mostly formulated and implemented under the auspices of the World Health Organisation (WHO).

As Hirschberg, Littmann and Strech explain in the edited volume Ethics in Public Health and Health Policy, central to both medical care (for ill individuals in health facilities) and public health measures (instituted by governmental authorities for the overall welfare of society) is the notion of the right to healthcare, which encompasses multiple dimensions, and ranges from concern for individual access to healthcare to the provision of a social structure conducive to healthy living. Yet the ultimate aim of public health measures is the overall well-being of the individuals who necessarily constitute the public — there can never be a public without the individuals who constitute it. Besides, both medical care policies and public health measures ought to be formulated and implemented with a deep commitment to respecting the dictates of morality, giving rise to medical ethics and public health ethics.

The ethical implications of COVID-19 vaccine mandates

As Hirschberg, Littmann and Strech explain, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, efforts aimed at improving and sustaining public health were primarily directed towards combating the spread of infectious diseases and plagues. However, as they further explain, the number of those falling ill and/or dying from infectious diseases was already on the decline before the discovery of the responsible pathogens (viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, etc.), and the development of effective treatments and/or vaccines. Hirschberg, Littmann and Strech further observe that this marked improvement in the quality of health can be explained by improvements in socioeconomic, environmental and living conditions, greater awareness of personal hygiene, and better nutrition. They point out that the nineteenth century thus saw the emergence of the sub-discipline of social medicine that focused on the effect that conditions such as poverty and relative social status had on the public’s health. Scholars of social medicine advocated for the establishment of a healthcare system that would not only attend to those who were already sick, but also promote health for the population.

Thus, public health policies are usually designed to address prevention and health promotion. Regarding this Hirschberg, Littmann and Strech write:

[P]ublic health measures can either target behaviour and lifestyle choices of the individual, or society more generally. The former applies to Public Health programmes such as the promotion of healthy diets, abstinence from tobacco or alcohol, and participation in medical screening programmes. Examples of the latter include immunisation programmes that achieve herd immunity and projects to eradicate certain pathogens regionally, nationally, or globally, e.g. by defining targets for lowering incidence of measles or polio.

Among the many ethical issues that arise from public health measures with regard to COVID-19 vaccine mandates, I highlight five below.

Individual liberty and well-being versus the public good

There are measures that might promote the well-being of a few individuals but hurt the public, and vice versa. While, in the name of public health, many would quickly resort to the principle that the majority ought to have their way, that principle disregards the dignity (infinite intrinsic worth), agency (capacity to act) and human rights (entitlements) of the minority by treating them as though they were of relatively little significance by virtue of their numbers.

In his On Liberty, John Stuart Mill, one of the greatest champions of liberal democracy, observed that the individual ought to be protected against the tyranny of the majority in the same way as he or she ought to be protected against political despotism. In fact, while many now think democracy is rule by the majority, in Considerations on Representative Government, Mill distinguished between true democracy in which all are represented, and false democracy in which only the majority is represented. Thus, COVID-19 vaccination ought not to be a requirement on the basis of the preferences or benefit of the majority, but ought rather to be made available to all those members of the public who choose to have it without the fear of losing their jobs or their access to public spaces and services.

Freedom to accept or decline a medical procedure

The notions of human dignity (infinite intrinsic worth), human agency (capacity to act) and human rights (entitlements) have usually been acknowledged in medical care through the principle of informed consent — that the doctor is morally obligated to explain in detail the implications of any medical procedure, and to let the patient decide whether or not to receive it. Anything less than this is paternalism, that is, the treating of adults as though they were children. Since public health measures, by promoting the health of a population ought to ultimately promote the overall well-being of the individuals that constitute that population, the principle of informed consent ought not to be violated in the name of public health.

In Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing, Miranda Fricker argues that there is a type of injustice in which someone is wronged specifically in his or her capacity as a knower (“epistemic injustice”). She distinguishes two forms of epistemic injustice — testimonial injustice (the injustice that a speaker suffers in receiving deflated credibility from the hearer owing to identity prejudice on the hearer’s part), and hermeneutical injustice (suffered by people who participate unequally in the practices through which social meanings are generated). In the era of COVID-19, humanity is suffering both types of epistemic injustice, as the principle of informed consent is blatantly violated through manipulative social and traditional media, and through intimidation by public authorities issuing vaccine mandates. Indeed, populations are now regularly treated as though they are devoid of knowledge, and must therefore rely solely on instructions from political authorities purportedly to control the spread of the virus and to take care of those who fall ill from it. This approach challenges our belief in human dignity, human agency and human rights, as it reduces us to helpless, ignorant beings who must wait for government to tell us what to do, not only about our conduct in public, but also what to expose our bodies to (read “vaccine mandates”).

The individual ought to be protected against the tyranny of the majority in the same way as he or she ought to be protected against political despotism.

Currently, the narrative in social and traditional media is that the vaccine is a must, and any information about its adverse effects is quickly suppressed or explained away. This manipulative approach is evident in the talk about “vaccine hesitancy”, as though all who have so far refrained from taking the “vaccine” will eventually “come round”. A more honest discourse would have acknowledged vaccine enthusiasm, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccine rejection. Besides, the individual’s freedom is often infringed on the grounds that members of the public are not adequately equipped to make informed decisions about their own health. This amounts to treating adults as though they were children (“paternalism”). The Ottawa Charter, which focuses on patient empowerment and the strengthening of health literacy, is relevant in this regard, as is health communication, encompassing multiple levels, from the formulation of written information on specific diseases to educational campaigns aimed at the general public.

Inadequate public health communication was evident when a Kenyan citizen filed a Constitutional Petition against the vaccine mandate issued by the Kenyan government on 21st November 2021. Mutahi Kagwe, Cabinet Secretary for Health, announced that there was no vaccine mandate, and that therefore no one needed to have gone to court. At the same time, he reiterated that the unvaccinated would be denied in-person access to government services from 21st December 2021. The import of that announcement was that “There is a vaccine mandate and there is no vaccine mandate”. Furthermore, on 22nd December 2021, Health Chief Administrative Secretary Mercy Mwangangi announced that one would have to show proof of vaccination to enter public spaces such as buses, grocery stores, restaurants and game reserves. This set of statements must surely be categorised as bad public health communication.

Besides, Cabinet Secretary Mutahi Kagwe had sought to justify the vaccine mandate on the basis of the Public Health Act. However, Section 36 (d) of the Act addresses situations in which Kenya appears to be existentially threatened by any formidable epidemic, endemic or infectious disease. Yet the public health data shows that COVID-19 is not leading to massive deaths that would warrant invoking these provisions. The Public Health Act is also subordinate to the Constitution of Kenya in which the Bill of Rights is enshrined. As such, it cannot legitimately serve as a basis for COVID-19 vaccine mandates, but only for vaccine programmes. Furthermore, the dominant COVID-19 narrative emphasizes that the vaccines do not rule out one getting infected, but rather reduce the chances of hospitalization and death. Thus, vaccine-free shoppers or travellers in public transport risk their own lives, not those of fellow shoppers or fellow travellers. As such, forcing them to be vaccinated is a violation of their personal freedoms entrenched in the Constitution of Kenya 2010.

In sum, public health authorities are violating the ethical principle of informed consent by compelling members of the public to take COVID-19 vaccines. Furthermore, by making online databases accessible to a large number of people to verify the vaccination status of individuals, health authorities are also violating the principle of patient confidentiality.

Responsibility for adverse effects of vaccines

It is common knowledge that each and every vaccine has adverse effects. As such, the individual has a right to accept or decline a vaccine because it is he or she who bears any adverse effects that it may produce. Yet by enforcing COVID-19 vaccine mandates, health authorities are blatantly disregarding this important consideration. As David Ngira and John Harrington explain, a system of quality control before the deployment and use of medicines in Kenya is set out in the Pharmacy and Poisons Act, the Standards Act, the Food, Drugs and Chemical Substances Act, and the Consumer Protection Act. They however point out that none of these Acts provides for comprehensive compensation after deployment and use of vaccines. Yet any monetary disbursements that citizens might receive for adverse effects of vaccines cannot possibly restore them to their previous state of health, and must therefore be viewed more as tokens than as adequate compensation.

A more honest discourse would have acknowledged vaccine enthusiasm, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccine rejection.

What is more, observe Ngira and Harrington, to minimise liability and incentivise research and development, pharmaceutical companies require states to undertake to meet any costs arising from successful suits against the pharmaceuticals for any harm caused by vaccines. Put simply, the victims would be awarded for damages through their own taxes rather than through the profits of the vaccine manufacturers. Besides, as Ngira and Harrington also explain, in Kenya’s legal environment, victims of adverse effects from vaccines would have to demonstrate that the vaccine maker or distributor fell below widely accepted best practice, and yet acquiring the evidence to prove this and finding experts in the sector willing to testify against the manufacturer can be very difficult.

Ngira and Harrington further note that while the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) have undertaken to honour a one-year compensation (“indemnity”) for adverse effects of AstraZeneca vaccines distributed in Kenya which allows victims to be compensated without litigation up to a maximum of US$40,000 (approx. KSh4 million), COVAX has indicated that the scheme will end once the allocated resources have been exhausted. This is a matter of concern, because there is no evidence that side effects of the vaccine fully manifest within a year. Besides, one wonders how the allocated resources for compensation were arrived at, bearing in mind that no one would have had information on how much resources would actually be needed for this purpose. Furthermore, according to Ngira and Harrington, beneficiaries of the COVAX compensation scheme are barred from pursuing compensation claims in court. COVAX also requires that before governments receive its vaccines, they undertake to pay any damages awarded to victims of adverse vaccine effects against manufacturers in any lawsuits.

The foregoing considerations lead to the conclusion that the individual, as the one who bears the full brunt of any adverse effects from COVID-19 vaccines, ought to be free to accept or decline them.

Debatable use of some primary prevention programmes

According to Hirschberg, Littmann and Strech, there is the question of the use of some primary preventive programmes such as vaccination campaigns, cancer screening, and assessment of psychological malfunctions. They further observe that problems that arise in this context include, but are not limited to, unnecessary treatment, financial interests of actors, and the role of pharmaceutical companies. For example, in Deadly Medicines and Organized Crime: How Big Pharma Has Corrupted Healthcare, Peter Gotzsche shows that drugs are the third leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer, and illustrates how pharmaceutical companies have developed toxic drugs that have caused untold suffering to many, and how law courts have awarded damages to the injured. Similarly, Neil Z. Miller discusses 400 scientific papers that show how vaccines have caused injuries, and how policy-makers ignore this information.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, the public was told that once the vaccines are developed and procured, those who receive them would be safe from the virus; then more recently it has been announced that those who are fully vaccinated will need a “booster shot” after six months. The question arises as to whether the “booster shots” are really necessary, or simply the innovation of the big pharmaceutical companies to make more profits, which would be a case of conflict of interest. Besides, it is not clear if humanity will ever be free from the vaccines if people will be required to take boosters every time a new variant emerges. What is more, while there is wide consensus among virologists on the effectiveness of natural immunity, very little is being said about this, giving the false impression that humanity’s hope only lies in the vaccines, as though humanity has not weathered numerous viruses without vaccines for millennia.

Monitoring and evaluation of public health measures

According to Hirschberg, Littmann and Strech, public health measures ought to be analysed within a framework that takes into consideration how decisions to implement the measures were reached, and how the expected impact can be evaluated and regulated effectively. As such, write Hirschberg and her colleagues, all phases of planning, implementation and evaluation of a public health measure should take into account the available scientific evidence.

In the edited volume Ethics in Public Health and Health Policy, Marckmann and his colleagues address the question of what strategies are ethically appropriate to achieve sufficiently high rates of influenza vaccination among healthcare personnel in long-term care facilities for the protection of the elderly care home residents under their charge. They contend that mandatory influenza vaccination for healthcare personnel can only be justified if the available empirical evidence on the effectiveness of the vaccine is more conclusive, and if all other less restrictive measures have failed to achieve a sufficiently high vaccination rate.

Beneficiaries of the COVAX compensation scheme are barred from pursuing compensation claims in court.

In view of the foregoing considerations, monitoring and evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine mandates ought to address the following four questions: To what extent were decisions to implement COVID-19 vaccine mandates transparent and participatory? How effective have the COVID-19 vaccines been in limiting the spread of the virus? In the light of a holistic conception of health as entailing physical, social and mental well-being, are vaccine mandates the most effective way to deal with the spread and impact of COVID-19? What is the impact of COVID-19 vaccine mandates on the overall physical, social and mental well-being of citizens?

Which way forward?

In view of the foregoing considerations, it is high time we insisted on respect for the Bill of Rights in the Constitution of Kenya 2010 that upholds the autonomy of the person and proscribes discrimination. It is high time we upheld the national principle of public participation in the formulation of public health policies. It is high time we insisted on the right to information, which implies the right to uncensored information, including free access to all shades of opinion regarding the safety or danger of taking the COVID-19 vaccines, and personal testimonies of those who have taken them, as well as reasons advanced by those who have refrained from taking them. In the end, what we are dealing with here is not simply the right to accept or decline the COVID-19 vaccines, but rather the whole range of individual freedoms, which implies the limits of state action. In sum, it is squarely within the mandate of the state to institute vaccine programmes, in which it makes vaccines available and seeks to convince citizens to receive them. However, vaccine mandates are instances of state overreach, as they violate human dignity, human agency and human rights, thereby eroding the very foundation of democratic society. If government can determine what goes into my body, what remains of my personal liberty?

Ideas

Development as Maendeleo and Its Undergirding Capitalist, Violent and Brutal Nature

Graham Harrison argues that all development is capitalist development. Based on his recent book, Developmentalism, he argues that development is not only risky and likely to fail but also very unpleasant. Contemporary notions of development see it is as a stable, incremental, and positive process but this is a fantasy in which capitalist development is reimagined as a planned, inclusive, and socially just modernisation.

My book Developmentalism starts with speculation. It imagines Tanzania in 2090 as a middle-income country. Average incomes are an adjusted $12,000; wage labour has expanded and become more regulated; the fiscal effort of the state has improved; large-scale infrastructural investments have increased and generated a more densely connected national market; production has diversified; rates of saving have increased; technological innovations have taken place and been embedded in local production chains.

One might respond to this futurology by arguing that it is a fantasy that ignores well-known diagnostics of Tanzania’s—and more generally Africa’s—development problems and failures. The dependency-minded thinker might refute the optimistic 2090 prospective by arguing that Tanzania is locked into an exploitative global capitalism that makes this kind of transformation impossible. The outcome: Tanzania—and again by extrapolation many other African countries as well—cannot develop because of some combination of its own properties and its location in a global economy.

The book argues that these responses are misguided. There is nothing in Tanzania’s current condition that looks exceptional or categorically different to any other country. There is no need to foreclose the possibility that Tanzania will be a middle-income country in 2090. Yes: Tanzania is unique; it has its own troubled historical and geographical inheritance; and it faces very significant challenges. But, so does everywhere else.

Capitalist development

One of the most powerful bourgeois ideological sleights of hand has been the naming of capitalist development as simply development. ‘Development’ discursively serves to naturalise what is a profoundly disruptive and political transformation, a transformation based in an imposed reallocation of property and wealth that relies on an invigorated and restless putting to work of people, requiring sustained and muscular state action. A transformation, above all, that is extremely risky and unlikely to succeed.

Development is capitalist development. This means not only that it is very risky and likely to fail but also that it is very unpleasant. The bourgeois coinage of development is that it is stable, incremental, and positive sum. In a word: liberal. Liberal development strategies—operationalised through a massive institutionalisation of international aid from the late 1950s—is in essence a theatre of global fantasy, a fantasy in which capitalist development is reimagined as a planned, inclusive, and socially just modernisation. The ideological erasure of enclosure, corporal punishment in law, forced labour, slavery, genocidal frontier expansion, theft and fraud, and war from the concrete manifestations of capitalist development has been sustained through the rolling out of a multi-trillion-dollar aid industry underpinned by an international elite institutionalism.

The fact is that capitalist development is fundamentally Hobbesian: nasty and brutish; destructive of existing community and extremely exploitative. It is in the DNA of capital’s ascendance that it remakes societies for its own purpose and the foundation of that purpose is not ‘making money’ or ‘earning income’ (the liberal vocabulary) but maximising profit, and extracting surplus labour: again and again, maximally and forever.

This brings me to two cardinal points that address our focus back to Tanzania or many other African countries. Firstly, that capitalist development requires the emergence of strong, purposeful, and well-resourced capitals. Secondly, that the conditions under which these emerge are, vitally, politically secured. Let me comment briefly on each.

In relation to the first point, we should note that much of the more progressive mainstream development discourse revolves around capabilities, microfinance, poverty reduction strategies, participatory development, empowerment, and resilience. All of these aid-driven devices are variations on a theme which the book describes as strategies to allow mass populations to ‘enjoy poverty’. That is, to live in an enduring and untransformed condition of material scarcity in meagre relative comfort. This discourse is at heart—and despite the often pleasing imagery it purveys—neoliberal. The story goes something like this: the enhanced capabilities of an individual lead them to secure a loan that allows them to earn a little more money that brings them to purchase a second-hand motorbike, a solar panel, a corrugated roof or a three-month class at a night school to learn accounting methods. Often told in vignette, these narratives bear slender connection to the major engines of poverty reduction which reside in those zones of capitalist industrialisation in northeast Asia and elsewhere in which tens of millions of people have experienced increases in income. All of the evidence indicates that capitalist industrialisation generates poverty reduction not through individual or community vignettes but through the structural changes wrought by capitalist industrialisation.

So, capitalist development is nasty, brutish, and impoverishing and also the world’s most tenacious engine of poverty reduction. It might seem that there is a contradiction here, but it is only apparent, not substantive. Capitalist development is the rolling out of what Anwar Shaikh calls turbulent trends: a collision of disorders set in unstable social relations that in their own dynamics generate the conditions of possibility for a generalised improvement in mass material well-being. Conditions of possibility, no more than this. There is no modernisation-style certainty of mass consumption; there is, paceThe Economist, no inexorable rise of a global middle class. But, in a way that is historically unprecedented, capitalism presents the possibility that a level and breadth of shared wealth can be achieved. This possibility depends on levels of economic growth and productivity and the strength of social mobilisation to makes claims on the commonwealth that capitalism generates and alienates.

The second point indicates what is, intellectually, a considerable lacuna in studies of capitalist development: its normative foundations. The major attraction of liberal visions of (capitalist) development resides in its ability to suture over the violence. The liberal vision is, to twist Rousseau, all freedom, and no force. This is a seductive fiction. It evades what is the most important political question facing any state that aspires to achieve capitalist development: how to engineer the social transformation within which capital can ascend into a dominant position within a national political economy. But this question is unavoidable. The book goes through variants of an answer to this question: England, America, Japan, Taiwan, Israel, China. All different; all the same. All extreme, not exceptional. All coercive, all risky. Only enjoying success after generations of uncertainty, chaos, and violence, and even then, success is not permanent. Developmentalism argues that, in radically different geographical and historical circumstances, all of these states only succeeded in forging capitalist transformation when this transformation was seen as inextricably integrated into a major-order or existential threat to sovereignty. Forging a nation, securing a border, or consolidating a besieged elite’s rule… in these circumstances in which states are seen as inextricably part of a project to promote the ascendance of capital one can identify the emergence of ideologies where capitalist development is not desirable but necessary. This ideological family is developmentalism.

So, the core question for African states that wish to pursue capitalist development is political-strategic. It is not about ‘getting the institutions right’ or good governance. It is broader and more ambitious than that and set in a temporality that is generational, not what economists call medium-term. It requires authoritarian state action—as it did in almost all other cases.

The book’s argument here is unlikeable: that there is no implicit commensurability between capitalist development and rights. If a ruling elite wishes to promote capitalist development it will only succeed if it deploys top-down and coercive state action—through law, programmes of social engineering, and also police action—to reallocate property, discipline workforces, secure exploitation, and push money into ascending capitals. One of the most unhelpful conflations in development studies in Amartya Sen’s development as freedom. To see development as an expanding freedom is to define away the central feature of capitalist development.

This is, of course, normatively very troubling. Does this perspective serve as an apology for forced resettlement, the detention of labour leaders, the top-down enclosure of land and resources for capital? No, it does not. There are three co-ordinates here.

In the first place, a theoretical orientation towards political realism. Realism is not amoral—this is a caricature that cannot really be found centrally in major Realist texts. Realism simply argues that normative politics is contextual: the modes of address to justice and right are not ideally-derived but produced in specific circumstances. So: the normativity of development does not disappear, it simply relocates into the processes of struggle themselves. This orientation leads to a better awareness of the political norms and normative contestation that accompany capitalist development. This is because the focus on rights is enriched through a recognition that socially-embedded political normativity is only in part about rights. It is also about a stability that allows people to see a better future, a sense of value in community and/or nationhood, religious cosmologies, economic growth, and other situated values which can only be understood through actual research. From a Realist point of view, these other value-clusters enjoy equal status with equally contextualised manifestations of rights norms and their significance and value are empirical matters. As a result, normative investigations from a Realist perspective do not insist on an a priori and idealised derivation from universal and absolute rights. And, they are all the richer for that.

Secondly, analytically, the book insists that there must be a separation of rights and development. They are not commensurable. They are antagonistic, or perhaps in the midst of capitalist transformation, highly strained: constantly requiring non-ideal play-offs. Capitalist development requires active deception from states; force strategically deployed; heavy ideological underlabour; secrecy and cronyism. In other words: politics… politics in the sense of making least-worst decisions in the midst of incomplete information and risk. Human rights scholars and activists work within a very well-specified moral universe that is founded on a meta-norm of justice. But this is not the province of the development scholar.

Thirdly, the political agencies that drive justice claims and indeed underpin the sustained demands for generalised material improvement emerge from concrete situations, not idealised norms. Consequently, we need to situate them in the very turbulence of capitalist transformation itself. As political economies change, so do the possibilities for political mobilisation. Normative agency itself develops within organisation, mobilisation, debate, and public action. This is, historically, a story of the changing organisation of labourers, but also of middle-class organisations, and mobilisations that intersect across poverty, race, gender, and other identities. None of these mobilisations exist because they are intrinsically or ideally right; they exist because they are produced within the transformations themselves.

In summary, the normativity of capitalist development is a non-ideal pluralised normativity that is composed within transition itself. It does not accept rights as its master norm because to do so would be to relinquish the necessary acceptance that capitalist development is not rights compatible.

All of which takes us to Rwanda, the African country that ends the case studies in the book. The Rwandan government is clearly not a ‘rights state’. What kind of a state it is, is still intensely contested. Rwanda does illustrate what a contemporary developmentalism might look like. Its future is very uncertain, but the government constantly and heavily claims otherwise, and portrays the government’s strategy as one of national revitalisation and esteem. It has used covert and extra-legal devices to allocate property and wealth in ways that have, arguably and in some instances, been based in securing expanded circuits of accumulation rather than simply graft. It has achieved a high degree of re-engineering of its rural areas through diktats on habitation, cropping, water usage, the formation of co-operatives, agrarian-ecological zoning, village governance, and performance management. It has invested in the infrastructure of an upgraded service economy: IT, hospitality, air freight, and national highways. It has done all of this whilst consistently reiterating a discourse of national economic transformation. The Rwandan government, in the midst of its authoritarianism and security obsessions, pins its legitimacy on its ability to generate development through an ascendance of capital. Its chances of success are slender; its record on human rights is poor; the challenges it faces are major-order or even existential. In short, it is, for now, developing.

–

This article was published in the Review of African political Economy (ROAPE).

Graham Harrison’s book Developmentalism: The Normative and Transformative within Capitalism is published by Oxford University Press.

-

Op-Eds1 week ago

Op-Eds1 week agoAfrica: The Russians Are Coming!

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoThe Wagalla Massacre: What Really Happened

-

Long Reads1 week ago

Long Reads1 week agoNon–Animal Pastoralism and the Emergence of the Rangeland Capitalist

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoKenya Goes to the Polls in 2022: But Where is the Nation?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSudan: The Storm Gathers in the Desert in Wave of Darfur Violence

-

Op-Eds1 week ago

Op-Eds1 week agoVoter Apathy Among the Youth Reveal Fundamental Flaws in Kenya’s Democracy

-

Videos2 weeks ago

Videos2 weeks agoDrought Management in Kenya Should Pivot from Crisis to Risk Management

-

Videos1 week ago

Videos1 week agoThe Challenges of Implementing The Community Land Act in Kenya