Data Stories

Deedha: How Pastoralists Communities Are Effectively Managing Drought and Conflict

With climate trend likely to worsen, it is crucial now for development partners, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and policymakers to rethink climate change adaptation and management in light of pastoralist’s indigenous knowledge and traditional resource governance structure such as Deedha to protect pastoralism which has continued to provide a lifeline to millions of households in the horn of Africa.

The first known drought in Northern Kenya was about 120 years ago (Wajir 1901, Mandera and Garissa 1902, Tana River 1905, and Isiolo 1927). Since then, 30 major droughts have been recorded in Northern Kenya. While a slow-onset disaster, drought occurrence has reduced to an interval of every 1-2 years in the last two decades.

Despite Africa’s minimal role in global warming, climate risks in Africa are growing bigger and continue to impact negatively rural agriculture and the pastoral economy.

In northern Kenya, drought often results in loss of lives and livelihoods, forcing thousands of households to drop out of pastoralism. Additionally, the Lack of rains undermines the growth of pasture and water availability for both humans and livestock. And as scarcity sets in, the use, control, and access to pasture and water are contested, often leading to risks of violent conflict.

Drought uncertainty triggers an old age survival strategy; – mobility where pastoralists either move to escape drought, conflict, or both. This strategy is incorporated within a traditional resource governance mechanism called Deedha amongst the Borana pastoralists group living in southern Ethiopia and Northern Kenya counties of Isiolo and Marsabit.

Practiced over a century, the system is elaborate; ‘it considers and plans how pasture and water resource’ is planned to last between seasons. Unique and structured, Deedha planning depends on the number of rains received and the pasture regenerated. So effective is the ‘system’ that the knowledge has supported the rearing of cattle to date despite high vulnerability and weak resilience traits.

For a long time in Kenya, cattle keeping has remained synonymous with the Maasai people. Yet in Kenya’s north and southern Ethiopia, the Borana communities have kept cows for equally long periods, so valued attached is that they have family names.

Various groups, including men, women, and young men, have also composed songs praising the cow’s beauty, walking style, milk yields, and how the herd owner moves around with them in the best of rangelands with constant surveillance against the raiders.

So emotive is any cattle disposal plan that a family meeting must be called, where reasons are evaluated to ascertain whether the sale is justified or not.

Another anecdote is also told of how various species respond to different needs, particularly water where camel would stay for a more extended period, followed by goats and sheep and cow in that order. At the same time, this story avers different resilience traits; the Boran has refused to divorce themselves from cattle keeping despite scaled up advocacy on the need for livelihood diversification in the wake of climate change and conflict risks.

Promotes Sustainable use of rangelands

Founded on the principle of sustainable use of the rangelands, the Deedha system is reciprocal. It encourages sharing resources and providing a safe drought haven for other pastoralist groups from other fragile counties such as Wajir, Garissa, Marsabit, Samburu, and even Laikipia.

The system is designed to encourage mobility over large tracts of land, helping the pastoralists break the pest cycle, aerate the soil (breakdown of soil with hooves), and manage unwanted vegetation.

The institution of Deedha is headed primarily by an elder, with each area having its Deedh (traditional grazing area to a particular group), which is linked to other deedha’s.

Informal but highly effective, the Deedha employs critical rangeland management, where the systems consider rangeland planning based on ecological vulnerabilities, livestock populations, an anticipated influx in determining when and where livestock moves, and whether there is a need for activation of the strategic boreholes.

The system partitions the rangeland into three grazing parts as dry, wet, and drought grazing areas, with also flash floods along the Ewaso Ngiro River considered as a season and blessing due to pasture regeneration in the swampy areas. In managing and protecting the rangelands, the Deedha traditional systems discourage sedentarization in strategic rangeland as part of conservation strategy after the use and boreholes areas, where Genset/pumps are mobilized during drought crises and demobilized on the fall of rain.

Manage drought and conflict

The system also incorporates the young people into Deedha resource planning and use and this is for two reasons; undertake pasture and security surveillance (Aburu and shalfa) in the far-flung Deedha’s which borders known or perceived enemy territory.

The system is so unique that critical access planning is done based on anticipated risks and livestock (species) vulnerabilities where Hawich (Milking herd) and non-milking herds (Guess) are split as defined by production and physical traits, respectively.

Hawich (Milking herds) are lactating, and some old and weak female breeds while non-Milking (Gues) are young female and male breeds with the ability to trek long distances searching for pasture and water. The system also calls for the protection of migratory and watering routes. While water for all livestock species is a priority, this customary system prioritized water for livestock in transit and the donkey over other livestock species for its role in household management. The system’s effectiveness has also seen it advocates for the protection of watershed areas and ensuring the cleanliness of the water point environs after all the livestock has been watered.

The Deedha also has in place resource sharing plans internally and externally, where Deedha in one location consult another Deedha before any decision is made. Such arrangement is also captured and advocated for by more recent attempts in enhancing resource sharing and ending conflict through such declaration as the Modogashe-Garissa, first entered in 2001 which calls for strengthening of resource governance and sharing framework between communities during drought. Thus, Deedha proactively enhances resilience through resource sharing and a framework for negotiations between communities during drought.

While Isiolo also had its fair share of drought, the use of this highly effective system has cushioned pastoralist group in Isiolo against the drought, only making foray into other communities’ rangeland in 1992 when Isiolo livestock moved to then Moyale District, Kauro in Samburu in 2000 and 2017 again to Moyale. The migration in 2017 was necessitated by fear following conflict escalation between the Borana and Samburu, leading to loss of 7 lives and over 3000 head of cattle in what the local Borana communities cite as security imbalances created by the Northern Rangeland Trust (NRT) to instil fear and force local pastoralists communities to abandon key strategic drought reserve in Chari Rangelands in favour of wildlife conservancies.

Untold, Deedha also calls for the protection of endangered tree species such as Acacia, Anthath and Qalqalch in which users are not allowed to overexploit, with individuals found out on the wrong punished. Equally, the system put communities at the Centre of wildlife conservation as it discourages reckless killing either for food or even trophies. The system also advocates for leaving water in the trough for wildlife to access in areas where the only water sources are deep wells.

Deedha is an example of bottom-up ‘law or rules’ for rangeland management; it addresses environmental and wildlife conservation. Like in predictive climate science, Deedha elders consider planning on how the previous seasons have performed. Further, the elders can predict trends and rain behaviour patterns based on Uchu, who closely work with the institution of elders.

With climate trend likely to worsen, it is crucial now for development partners, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and policymakers to rethink climate change adaptation and management in light of pastoralist’s indigenous knowledge and traditional resource governance structure such as Deedha to protect pastoralism which has continued to provide a lifeline to millions of households in the horn of Africa.

Support The Elephant.

The Elephant is helping to build a truly public platform, while producing consistent, quality investigations, opinions and analysis. The Elephant cannot survive and grow without your participation. Now, more than ever, it is vital for The Elephant to reach as many people as possible.

Your support helps protect The Elephant's independence and it means we can continue keeping the democratic space free, open and robust. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our collective future.

Data Stories

Punitive Government Policies Jeopardise Kenya’s Food Security

The government is criminalising Kenyan farmers and leaving the country’s food security at the mercy of multinational corporations.

By 2021 your typical Kenyan smallholder farmer was producing 75 per cent of the foods consumed in the country. Yet the draconian laws imposed on the agriculture sector by the government have been facilitating their exploitation by private sector actors including multinational corporations. This is in total contradiction with President Uhuru Kenyatta’s move to include food security in his Big Four Agenda and begs the question of how the country can achieve food security when farmers are discouraged from producing food by these punitive laws.

Recently, there was an uproar on social media regarding the Livestock Bill 2021. The point of contention in the yet to be gazetted Bill is a clause that bars Kenyan farmers from keeping bees for commercial purposes unless they are registered under the Apiary Act. The government, through the Permanent Secretary for Livestock Mr Harry Kimutai, tried to justify this by saying that the aim of registering beekeepers is to commercialise beekeeping instead of it being a traditional practice.

Local pastoralist, agrarian and forest-dwelling communities have practiced beekeeping since time immemorial and it has been part of the subsistence economy of smallholder farmers who pass on this rich knowledge and expertise from generation to generation.

Bee-reaucracy

In its current form, the Livestock Bill 2021 will drive smallholder beekeepers out of honey production and pave the way for multinational corporations under the guise of regulating the sector. It is no different from the Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy 2019-2029 that seeks to move farmers out of farming into “more productive jobs”, opening the door for their exploitation and impoverishment by agro-capitalists.

In a recent media interview, Mr Kimutai said that Kenyan honey is contaminated with pesticide residues. But if the government is indeed concerned about improving honey production, it should start by banning the use of toxic pesticides that are detrimental to bees and contaminate the quality of honey. Pesticides such as Deltamethrin have been found to be toxic to bees yet they are still used in Kenya.

Local pastoralist, agrarian and forest-dwelling communities have practiced beekeeping since time immemorial.

Section 93 subsection(1) of the Bill bars the importation, manufacturing, compounding, mixing or selling of any animal foodstuff other than a product that the authority may by order declare to be an approved animal product. This offence attracts a fine of KSh500,000 or imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months, or both.

Smallholder livestock farmers in Kenya have been growing “napier grass” to feed their cows and for sale to other farmers. Do these new regulations mean that they shall be committing an offence by growing their own feed and selling it within their localities?

Another punitive regulation is the Crops (Irish Potato) Regulations 2019, that requires transporters, traders and dealers to be registered with their counties, failure to which they face up to KSh5 million in fines, three years imprisonment, or both. This regulation also punishes an unregistered farmer with a one-year imprisonment or KSh500,000 or both, for growing a scheduled crop. It is no coincidence that capitalist-funded organisations like Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) applaud the Irish Potato regulations as a new dawn for Kenyan farmers.

Through the Seed and Plant Varieties Act 2012, the government once again fails to protect farmers from capitalist exploitation. Part 1 of the Act defines selling as including barter, exchange and offering or exposing for a product for sale, taking away a farmer’s right to sell, share and exchange seed, a right that is recognised in the constitution.

Through the Seed and Plant Varieties Act 2012, the government once again fails to protect farmers from capitalist exploitation. Part 1 of the Act defines selling as including barter, exchange and offering or exposing for a product for sale, taking away a farmer’s right to sell, share and exchange seed, a right that is recognised in the constitution.

Part 2 section 3 of the Act prohibits the sale of uncertified seed. The good old practice of selling and sharing seeds is further criminalised in section 7(5) which requires only seed appearing in the Variety Index or the National Variety List to be sold. This limits farmers from selling their varieties which they have been sharing, exchanging and selling for generations. Moreover, this automatically means that farmers selling their seed varieties are committing an offence if such varieties are not listed in the index.

Further, section 18 part 4 of this act allows for the discovery of a plant variety whether growing in the wild or occurring as a genetic variant, whether artificially induced or not. This section allows for the discovery of farmers’ indigenous seeds by multinational corporations keen to patent them for profit.

It is no coincidence that capitalist-funded organisations like Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) applaud the Irish Potato regulations as a new dawn for Kenyan farmers.

The implication here is that since farmers’ seed varieties are not registered or owned by anyone, anybody can obtain the seeds of any crop variety, apply for their registration and claim their “discovery”. Farmers who have been conserving and reusing the “discovered” seeds will then lose the right to continue doing so and they will be required to pay royalties to the new “owners” of these seeds.

This act contravenes certain provisions of the constitution, in particular Article 11 (3) (b) of the Kenya Constitution 2010 which states that parliament shall enact legislation to recognise and protect the ownership of indigenous seeds and plant varieties, their genetic and diverse characteristics and their use by the communities of Kenya.

Foreign laws

The parliament has forfeited its obligation to enact laws that protect and enhance our intellectual property rights over the indigenous knowledge of the biodiversity and the genetic resources of Kenyan communities as mandated by Article 69 (1) (a) of the Kenyan constitution. It has allowed external actors to pirate local resources and trample indigenous rights.

Patenting indigenous seeds, barring farmers from keeping bees, and regulating the growing and selling of animal feed and potatoes is theft of the commons. The government is in cahoots with large corporations determined to kill the smallholder farmers’ sources of livelihood while singing about food security being part of the Big Four Agenda.

What sense does it make to frustrate smallholder farmers who grow 75 per cent of our food to serve the interests of imperialist multinational corporations keen on holding our farmers at ransom through abhorrent fines?

What sense does it make to frustrate smallholder farmers who grow 75 per cent of our food to serve the interests of imperialist multinational corporations keen on holding our farmers at ransom through abhorrent fines?

Patenting indigenous seeds, barring farmers from keeping bees, and regulating the growing and selling of animal feed and potatoes is theft of the commons.

It is time to reclaim and protect the commons that our communities have for a very long time thrived on. In her book Reclaiming the commons Dr Vandana Shiva points out that indigenous communities, including farmers, co-create and co-evolve biodiversity with nature, practises that have seen them overcome ecological challenges for generations. Our policies, plans and laws need to protect these practices for posterity.

Our parliamentarians should endeavour to defend our biodiversity, indigenous cultures and national systems – reclaiming the commons. We need policies that will allow farmers to produce food using indigenous seeds that are readily available and that they can be share amongst themselves. We need policies that will allow farmers to produce safer and more healthy food in an environmentally safe way, not punitive policies designed to eliminate farmers and have our food system controlled by corporations out to make profits at the expense of our health and our environment.

Data Stories

Tech Disruption in the Agricultural Sector

The future of farming in Kenya counties, whether in knowledge sharing, collaborations, funding, or market access primarily lies in the farmer’s abilities to harness the respective strengths of the available and emerging Disruptive Agricultural Technologies. As the tech-platforms become cheaper, more available and affordable farmers yield and fortunes will likely inch upwards.

Disruptive technologies in agriculture (DATs) have been in Kenya since the early 1900s and can simply be defined as the digital and technical innovations that enable farmers and agri-firms to increase their productivity, efficiency, and competitive edge.

These platforms essentially help local farmers make more precise decisions about resource use through accurate, timely, and location-specific price, weather predictions. The agronomic data and information that they provide in Kenya is becoming increasingly important in the context of climate change. Besides, leveling the playing field, it can make small-scale or local marginalized farmers in Kenya to be more competitive.

Sophisticated off-line digital agri-tech can provide opportunities even in poorly-connected rural contexts, or with marginalized groups who have lower access to information and markets. In short, Disruptive Agricultural Technologies (DATs) are overturning the sector status quo.

Some of the key disruptive technologies in agriculture (DAT’s) include Waterwatch Cooperative in Kenya (Real-time alert system), Tulaa and Farmshine (Digital platform for finding buyers and linking buyers and sellers).

There is also Agri-wallet (platform for input credit/e-wallets/insurance products), dutch-based Agrocares operating in Kenya and Ujuzi Kilimo (portable soil testers, satellite images, remote sensing) as well as SunCulture (solar-powered irrigation pumps)

These platforms have helped to facilitate access to local markets in counties such as Makueni and West Pokot, improve nutritional outcomes, and enhance resilience to climate change. Disruptive agricultural technologies are designed to help stakeholders by reducing the costs of linking various actors of the agri-food system both within and across countries through faster provision, processing, and analyzing of large amounts of data.

The Disruptive Agricultural Technologies Landscape

Over 75% of Disruptive Agricultural Technologies are digital. The remaining 25% of non-digital are either focused on energy (solar), or producers/suppliers of bio-products for agriculture.

Approximately 32% of the Disruptive Agricultural Technologies aim to enhance agricultural productivity, 26% are working to improve market linkages, 23% are engaged in data analytics, and another 15% are working on financial inclusion.

According to a 2019 World Bank report, Kenya has become a leading agri-tech hub with nearly 60 scalable Disruptive Agricultural Technologies (DATs) operational in the country, followed by South Africa and Nigeria. Kenya is said to have the third largest technology incubation and acceleration hub in the region. Examples of those technologies in Kenya include: Data-connected devices which use ICT to collect, store, and analyze data. This includes GPS, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. The Africa’s Regional Data Cube hosted in Nairobi,Kenya is a tool that helps various countries address issues related to agriculture, water, and sanitation.

The use of robotics and automation in farming in Kenya has gained widespread acceptance. For instance, drones are used to monitor and improve the efficiency of agricultural operations and its usage is governed by the Civil Aviation Act.

Majority of farmers in Kenya are smallholder farmers and having access to Disruptive agricultural technologies helps even the competition with medium and large scale farmers as tools are created for both low and high connectivity areas.

Over 83 percent of Disruptive agricultural technologies are e-marketplaces that do not require high connectivity. Example is Twiga Foods whose digital platform connects retailers and food manufacturers, delivering a streamlined and efficient supply chain.

Kenya’s financial sector is characterized by a robust mobile money ecosystem (MPESA) with over 70 percent of the population using mobile money regularly which increases its potential for farming for smallholder farmers.

Despite that one of the biggest challenges facing the agriculture sector in Kenya is access to finance. This is largely due to the high risk of loaning to small holder farmers. FinTech apps use alternative data and machine learning to improve the credit scoring of smallholder farmers.

These apps help minimize the gap between the demand for credit and the supply of financing for smallholder farmers. Kenya is a hotspot for agricultural apps. There are numerous organizations working on developing digital solutions that combine precision farming with remote sensing data.

Connectivity and Adoption of DATSs

A significant number of the existing digital tools and technologies can be utilized in areas with low network to improve the productivity of the agriculture sector. Despite the increasing number of mobile phone users in Kenya, the penetration rate among smallholder farmers remains relatively low.

It may be difficult for many of these smallholder farmers to adopt Disruptive agricultural technologies (DATs) due to the high costs, complexity and capabilities required. Meanwhile for large scale farmers, the DATs highly boost their productivity, especially if they have already developed the capabilities in-house to accelerate adoption of these tech platforms. Therefore, from the onset, we need to understand who uses the technology and the implications of this.

Kenya has a well-established start-up ecosystem, made up of mostly young, adaptive and brilliant innovators who are leveraging low-cost digital platforms. This is coupled with funding from international donors and incubation activities address agricultural value-chain issues. There is a mix of actors for Disruptive agricultural technologies depending on the categorization of the technology.

This ranges from DATS that support creation, facilitate adoption and oversee diffusion of innovation.

These actors need strong and cohesive ties, both between, the regulatory bodies, farmers, county leaders, financiers, state agencies, and fellow developers. The nature of the collaborations could be cohesive and cooperative, where all the local actors have shared goals, to fragmented, where not all actors are on board, causing resistance and slowing down the process.

Despite a myriad challenges these radical and innovative (DATs) are revolutionizing and changing the farming landscape in the counties and working with the Ministry of Agriculture using technologies to deliver agricultural services more efficiently and accountable.

The future of farming in Kenya counties whether in knowledge sharing, collaborations, funding, or market access primarily lies in the farmer’s abilities to harness the respective strengths of the available and emerging Disruptive Agricultural Technologies. As the tech-platforms become cheaper, more available and affordable farmers yield and fortunes will likely inch upwards.

–

This article is part of The Elephant Food Edition Series done in collaboration with Route to Food Initiative (RTFI). Views expressed in the article are not necessarily those of the RTFI.

Data Stories

Revealed: Majority of US Voters Support Patent Waiver on COVID-19 Vaccines

Shock poll reveals majority support for Joe Biden to suspend TRIPS and support global vaccination.

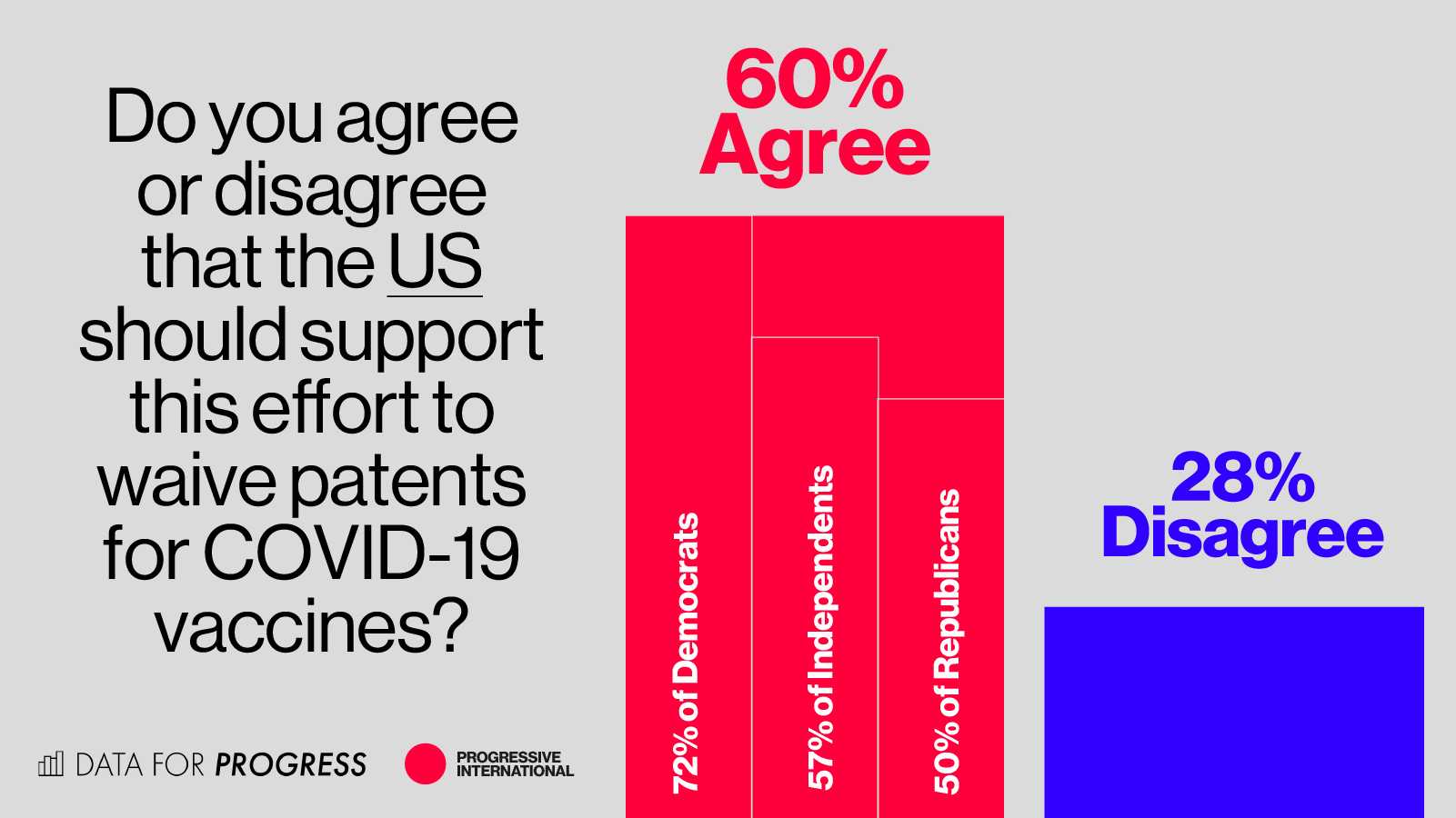

A new poll finds that 60% of US voters want President Joe Biden to endorse the motion by more than 100 lower- and middle-income countries to temporarily waive patent protections on Covid-19 vaccines at the World Trade Organization. Only 28% disagreed.

The survey, carried out by Data for Progress and the Progressive International, shows a super majority of 72% registered Democrats want Biden to temporarily waive patent barriers to speed vaccine roll out and reduce costs for developing nations. Even registered Republicans support the action by margin of 50% in favor to 36% opposed.

The new polling shows that “there is a popular mandate from the US American people to put human life and economic recovery ahead of corporate profits and a broken intellectual property system,” said David Adler, the general coordinator of the Progressive International. Burcu Kilic, research director of the access to medicines program at Public Citizen and member of Progressive International’s Council, called on Biden to “listen to Americans who put him in power” and “do the right thing.”

Due to WTO intellectual property rules, countries are barred from producing the current leading approved vaccines, including US-produced Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. In October of 2020, South Africa and India presented the WTO with a proposal to temporarily waive these rules for the duration of the pandemic so that vaccines can be manufactured across different countries, increasing their availability, reducing their cost and ensuring that they are delivered to everyone on earth as quickly as possible.

Due to WTO intellectual property rules, countries are barred from producing the current leading approved vaccines, including US-produced Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. In October of 2020, South Africa and India presented the WTO with a proposal to temporarily waive these rules for the duration of the pandemic so that vaccines can be manufactured across different countries, increasing their availability, reducing their cost and ensuring that they are delivered to everyone on earth as quickly as possible.

In the absence of the waiver, the current manufacturing and distribution rates are unlikely to stem the pandemic’s momentum, especially as new variants, which are more infectious and seem to evade the acquired immunity from prior infection or from the current vaccines, continue to emerge. The US under President Trump joined other richer nations to block them.

The shock poll reveals a level of public support for intellectual property waivers that will likely add to growing congressional pressure on Biden to join those pushing to save lives through a global vaccination drive. Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky is working on a letter to the president to which Schakowsky says more than 60 lawmakers have added their signature, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Senator Bernie Sanders, Chair of the Senate Budget Committee, responded to the poll saying the US should be “leading the global effort to end the coronavirus pandemic.” According to Sanders, “a temporary WTO waiver, which would enable the transfer of vaccine technologies to poorer countries, is a good way to do that.”

Responding to the new poll, Representative Ilhan Omar called on Biden to “support a waiver to boost the production of vaccines, treatment and tests worldwide,” arguing that it was “not just an issue of basic morality, but of public health.”

Adler argues, “US Americans know rigged rules to prop up big pharma’s profits are not in their interest. The longer the virus has to spread, the more it can mutate and become vaccine-resistant. Covid-19 anywhere is a threat to public health and economic wellbeing everywhere. If intellectual property restrictions are not lifted, the pandemic will go on for longer, killing more people and damaging more livelihoods.”

The threat to the Global South from vaccine apartheid is a “death sentence for millions around the world—and it is because giant pharmaceutical corporations would rather maximize profit than provide vaccines to people who need it,” according to Omar.

Sanders agrees, saying “the bottom line is, the faster we help vaccinate the global population, the safer we will all be. That should be our number one priority, not maximizing the profits of pharmaceutical companies and their shareholders.”

-

Videos2 weeks ago

Videos2 weeks agoEthiopia: Abiy Ahmed’s Choices – Negotiation or Calamity!

-

Op-Eds5 days ago

Op-Eds5 days agoElections? What elections? Abiy is Counting on a Military Victory

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoThe Evolving Language of Corruption in Kenya

-

Long Reads1 week ago

Long Reads1 week agoMuseveni’s Paradox, Class Dynamics and the Rise of Hustler Politics in Uganda

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoPan-Africanism in a Time of Pandemic

-

Long Reads1 week ago

Long Reads1 week agoReflections on the Kenyan Court of Appeal Proceedings in the BBI Case

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoProtests, Chaos and Uprisings: Lessons from South Africa’s Past

-

Long Reads1 week ago

Long Reads1 week agoThe President Who Burned Kenya’s Heritage, Humiliated Little Girls and Elderly Women